Speaker: Trevor Jackson

Subject: ‘Cemeteries of Oxford : more than a Century of History’

26 members with 4 guests attended our first talk of the year, a fair attendance for a cold January evening.

Our speaker was Trevor Jackson, who had previously given us a talk on the history of RAF Brize Norton. This time his subject took us through the history and development of the cemeteries in Oxford.

Background

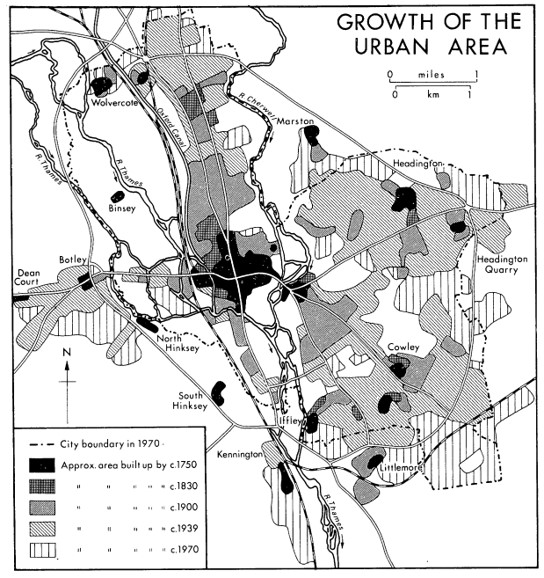

Between 2005 and 2017 Trevor was the Registrar and Manager of Oxford City’s cemeteries at Wolvercote, Botley, Rose Hill and Headington. He and his team were also responsible for maintaining the grounds of 11 closed Anglican churches in the city. Trevor came to the work after 30 years with the RAF, which included work around the repatriation of war dead from overseas operations, and the attendant management of service funerals.

Nineteenth Century Developments

Trevor’s talk took us through the reasons for the establishment and development of the cemeteries at Osney and St Sepulchre (Jericho) in the mid 19th century. In addition to the effects of regular cholera outbreaks, there were other capacity issues in existing cemeteries, where the practice of “continuous burials “ was no longer sustainable. However, both new cemeteries filled rapidly, with continuing cholera outbreaks, and so were closed to new burials from 1855.

New Capacity

For new capacity, land was sequestered in the late 1880s to create the three cemeteries of Rose Hill, Botley and Wolvercote, with a further cemetery established at Headington in 1928.

Using these examples, we learned something of the structural maintenance of cemeteries, using retaining walls and careful monitoring of underground subsidence and the attendant danger of falling monuments, and also the layouts to include specific areas for children and victims of sudden infant mortality.

Some Highlights

Sobering subjects indeed, but intermixed with these realities, we had insights into the use of the cemeteries as filming locations – including the filming of “Any Human Heart” which transformed Rose Hill cemetery to a New York location, and also an episode of the TV series “Endeavour” at Headington.

We looked at the chapel architecture for each of the four cemeteries, including gate lodges which have now become private dwellings, as well as some biodiversity initiatives amongst the necessary ground maintenance work.

Trevor’s talk also took in stories of individual WW2 service personnel, and something of the Commonwealth War Graves, particularly at Botley. We also learned of some famous names whose resting place is at the large Wolvercote Cemetery, which has the graves of JRR Tolkien, Sir Roger Bannister and Isaiah Berlin.

The evening was a fair mixture indeed, with no small amount of dark humour to make for an educational and entertaining time.