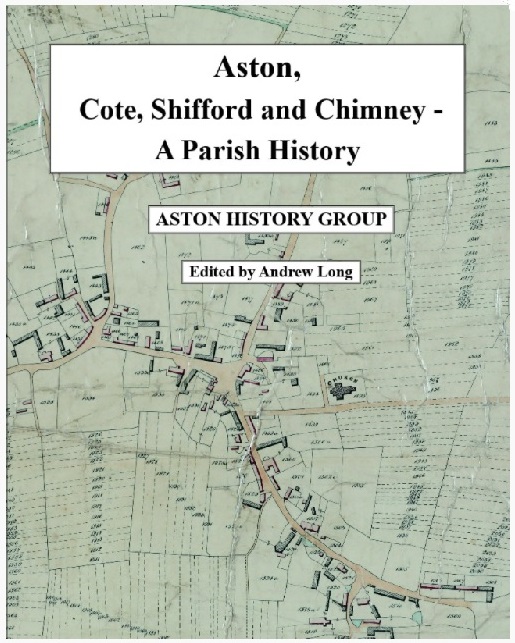

Published in March this year, a new book by the Aston History Group has come to our attention, as an exemplary historical overview of the Ozfordshire villages of Aston, Cote, Shifford and Chimney. A4 size with 210 pages and more than 300 photographs and illustrations (many in colour), this is an eminently readable volume which demonstrates rigorous research in an accessible format.

There are some interesting parallels with the Wychwoods area. Once primarily agricultural in character, the Aston, Shifford, Cote and Chimney hamlets were administered by the main parish at Bampton (just as Shipton was the main parish for Wychwoods area for many years). Aston got its own Anglican church (quite a monumental thing) in 1839 (funded locally and by The Church Commissioners). Milton acquired its Anglican church in 1853. The Aston hamlets have a strong Baptist history – as does our area, and the enclosures came quite late to them as it did for us in the Wychwoods.

“A Parish History” includes details which reflect the patterns and concerns of community life, mirrored in own Wychwoods villages over time. In particular, the special features on religion and agriculture cover social and economic developments that followed national trends.

In 16 chapters and 8 appendices, fully indexed, all aspects of life are covered in an easily accessible way. Here is a short outline:

Origins

The first two chapters cover some archaeological research which places the parish in the context of the sweep of history from Palaeolithic times through to the arrival of the Romans, and on to the Anglo-Saxons and finally the Norman Conquest. Highlighting for example, the Neolithic causewayed camp near Chimney, the Iron Age farmstead excavations at Shifford, the Shifford Sword, the key moments and artefacts around the late Saxon politics including Alfred the Great and onwards – there is much to inspire. These chapters end with Leofric’s Charter = a late Saxon document which mentions Aston and Chimney. The charter places the villages in the hands of the of the Bishop of Exeter, a situation confirmed at the Norman conquest and continuing until the 18th Century.

Two later chapters in the book are devoted specifically to the origins and key developments of the villages of Shifford and Chimney, again with lavish illustrations using maps, photos and diagrams.

Farming and Enclosure

The chapter on agriculture describes the changing landscape precipitated by the Enclosures Act finalised in 1855, the culmination of a process which had affected parishes throughout the country for a considerable period. Aston’s enclosures were sealed in 1852 and were among the last to be affected. Described in some detail are the earlier “open fields” systems operating at least since the 13th century, with later records of names and activities as well as example field plans.

Of particular interest is the establishment by 1593 of a group of parishioners called The Sixteens, elected annually, who oversaw the regulation of farming activity – and so uniquely outside of direct Manorial control which was the normal pattern. The research covers in some detail the post-enclosure life on the land and the effects of the Corn Laws, agricultural depression, and the activities of the Agricultural Labourers Union, familiar to students of life in the Wychwoods in those times. This chapter ends with fine images of the changes which continued in farming practice during the 20th century, with several anecdotes around the introduction of mechanisation.

Trades, Occupations, Services and Shops

This chapter includes a panoply of images of early to mid-20th Century working life. Thatchers, Carpenters, Blacksmiths, Aston Wood Yard and the Wagon Works are all covered. Maltsters, Tanners, Brickmakers and many more are described, with photographs which highlight a thriving community at work.

The Poor

The chapter on poverty and need throws up a great deal of interesting detail on how many parishioners made provision in their wills for the poor and needy. Examples are given, as well as descriptions of charitable trusts and friendly societies. Of course, as throughout the country, the parish was the provider of last resort, either through the workhouse system, or through “poor relief” to supplement low wages.

A fascinating picture is built up of the developments around assistance for the poor. This includes the arrival of Friendly Societies, including Aston’s Slate Club which was the last of the Friendly Societies to operate before the gradual changes brought about by an emerging welfare state from the early 20th century. Charming to see is a picture of and elderly couple, dressed in their best clothes – the first couple in Aston to draw the Old Age Pension.

Law and Order

Several examples are given of cases of varying criminal severity to show the various levels of misdemeanour tried in Petty Sessions, Quarter Sessions or Assize courts. A picture emerges of a law-abiding parish, with the main crimes linked to poverty. Included in the discussion of law and order is a short synopsis of its funding and development over the centuries, culminating in the creation of a national police force and the installation of Aston’s first police constable in 1857.

Transport

Images of transport through the years include maps, drawings of river transport including flash locks and river barges. The mobility or otherwise of parishioners is examined, with notes of bus transport and the coming of the railways.

Religion

We learn that surprisingly there was no dedicated parish church for the villages, and worshippers for the most part went to services in Bampton before the building of St James Church from 1839. Mapped onto a discussion on Wycliffe’s Bible, the development of non-conformist faith is well covered. An outline of non-conformist activity from the mid-17th century and earlier gives a picture a diversity of religious worship and practice, which can be understood as a function of the looser Manorial control alluded to in the chapter on agriculture and farming. Several pages are dedicated to the building of the parish church and describe its highlights.

Education & The Aston Training School

The development of school and education facilities from the mid-1700s to the present day is covered. There are plenty of illustrations, photos and discussions around the challenges all villages faced over the financing and structure of regular school facilities, These affected the poor as well as the better off. Particularly interesting are direct quotations from the reports of school inspectors over time, and anecdotes of some interesting behaviour amongst pupils. Jane Clarke’s training school for girls in service has its own chapter. This establishment, created in the late 19th century, became well-known as a training centre for girls otherwise ill-equipped for the rigours and skills of life in service.

Leisure

A lively chapter featuring the panoply of leisure activities to be had in the past 150 years are covered, including Aston Feast and the annual cherry fairs, plus of course activities around the public houses and organised singing and dancing. Copiously illustrated with memorabilia images, there is plenty of material around the several Coronation and Jubilee celebrations in the villages. Many photos of more recent events, especially sports and river-based activities make for an entertaining profile of village life.

Buildings

The changing needs and fashions which caused alterations and extensions to buildings over the years is the subject of a chapter which also illustrates a timeline of village expansion and infill. This reflects the lived experience of villages throughout the country. Here, the various housing types are described and illustrated with reference to available local building materials. An inventory is included of the many Listed properties in the four villages.

The Parish at War

Common ground with the Wychwoods is found with the descriptions of events around the arrival of Basque refugees in Aston during the Spanish Civil war, as well as the in-depth descriptions of World War II evacuees, activities and privations, which reflect those described in our own publication “That’s How It Was”. Also covered are the effects and key events of the English Civil War, echoes of the Napoleonic Wars and of course the Great War.

Appendices

These are – as is the whole publication – well-researched. In particular, the war memorial biographies of the fallen are expressive of a felt gratitude. Sections on population changes as well as lists of incumbent head teachers and ministers of religion over time are carefully recorded. We are even given a full list of the pub landlords past and present in the villages.

There is much to recommend this beautifully researched parish history. It reads as a fascinating story but is also a valuable reference tool for those who love and value the story of English village life.

DB / JB October 2021

To Buy a Copy

PRICE – £15.00 p&p £5.00 (UK) (Overseas please enquire)

Please complete the form below for details of how to buy your copy of the book