The following article by Wendy Pearse appeared in Vol 31 [ PDF here ] of the Wychwoods Local History Society Journal. It was published in 2016. It focusses in detail on the fortunes of Ascott families and develops the tale around 19th century Wychwoods emigrations, discussed in Martin Greenwood’s book “The Promised Land” which we reviewed recently.

In our affluent world of today, it is very difficult to visualise what life must have been like for the villagers of Ascott in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The Rev. Samuel Yorke, through the pages of the Leafield and Ascott Parish Magazine, and later the Chipping Norton Deanery Magazine, 1880-83, recounts various happenings and events but it is almost impossible to glean the reality of everyday life for the craftsmen and labourers of the village. What were the conditions like within the houses? How did they obtain their food and water? How about sourcing clothing and footwear? Where did they obtain fuel to heat their houses and cook their food? That particular period of the century hit the British countryside hard. Farmers were finding it difficult to compete with increasing imports from abroad. Wheat and refrigerated meat from other parts of the world were increasingly unloaded on British shores, thus lowering the price of the home market. Imported cattle were bringing in diseases to which indigenous breeds had little resistance. And the weather was atrocious, providing climatic conditions totally opposite to those necessary to aid the production of food. Farms were difficult to rent out, resulting in less available work for farm workers. Wages were poor, and the lower down the class system, the greater the problem of providing for a family. For many living in Ascott, daily life may have been dire indeed.

However, primarily for the young, there was a source of hope: the promised lands on the far side of the world beckoned. Apparently, a fair number of Ascott’s born and bred were prepared to seize this opportunity. The possibility of acquiring land of their own, and the chance of setting their foot on an upwardly spiralling ladder, proved difficult to resist. In the early 1870s many people left the Wychwoods to seek a new life in New Zealand, partly with the assistance of the emerging Farm Workers’ Trade Unions. But a decade later Perth and Western Australia appear to have had the most to offer to the youth of Ascott, and through the Deanery, we can follow a number of these youths as they set out on their greatest adventure.

In 1875 when Rev. Yorke and his wife Frances arrived in Ascott, it seems that Mrs Yorke proposed the establishment of a Night School for the village youths. This she pursued, with about 30 students ranging in age from twelve to the middle twenties. Apparently these young villagers were already giving thought to improving their lot in life. Five years later, Rev. Yorke reported that some of the earlier students had already taken advantage of their additional qualifications by joining the Railway Company, the Post Office, the Army or, indeed, by emigrating abroad. Three past students, Frederick White, Raymond Pratley and Jacob Moss had emigrated to Western Australia, where to all intents and purposes they were doing well. Raymond Pratley was the son of a farm labourer and Jacob Moss the youngest son of a shoemaker. They were approximately the same age, born in Ascott, and had probably known each other all their lives. Frederick White, however, was a few years younger than the other two and must have been only about 16 or 17 when he left England. This may have been due to family matters since his father, the village blacksmith, had died in the late 1870s, and his mother was left with other young children and an older stepson, so maybe he decided the time was right to make his own way into the world.

In 1880 in the last issue of the Leafield and Ascott Parish Magazine, Rev. Yorke reported that Mr Hyatt, whose family had farmed at Stone End Farm (now Ascott Earl House) for generations, had recently seen three of his grandsons depart for Australia: Frank Gomm, the son of his daughter living in Tackley, and Alfred and Edwin Townsend, sons of his other daughter Sophia, the widow of Edwin Townsend of Long House Farm in High Street. The Townsends, like the Hyatts, were a family of long-established Ascott farmers. James, an elder brother of Alfred and Edwin, had sailed for Australia in 1876, which was probably an added incentive to his younger brothers’ desire to emigrate. Alfred was 20 and Edwin, like Frederick White, only 16 or 17. The three young men sailed from London on the steamship Potosi on the 29th October 1880.

The S.S. Potosi, built in 1873, had been purchased by the Orient Line from the Pacific Company’s fleet only in the past year. She was considered a good, seaworthy vessel and was known for fast steaming. She had a gross measurement of 4219 tons, length 421 feet, beam 43 feet and the depth of the hold was 33 feet 5 inches. Following her initial arrival in Australia in July 1880, The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser reported, ‘ . .it is lit up at night with the new electric process (Siemens), and this is the first vessel that has been in this harbour lit up in such a manner; and the satisfaction the light has given is likely to lead to all the Orient boats being fitted up in a like manner. The second saloon is lighted in the same method, but in a lesser degree of brilliancy. The light in the saloon having been found to be too dazzling, gauze coverings had to be put round the globes to temper it. There are four of these globes, one under each corner of the large skylight in the main saloon. The Potosi is propelled by engines of 600 horse-power nominal, with inverted cylinders; these are two in number.’

In the Deanery of January 1881, Rev. Yorke reported, ‘The ship ‘Potosi’ of the Orient line [with the three Ascott youths bound for Perth, Western Australia] reached Adelaide after a voyage over the 12,000 miles of 43 days from London, including stoppages at Plymouth, St. Vincent and the Cape. In their letters received from the Cape, they say that the voyage thus far had been a most pleasant one, after passing Madeira and the Canary Islands, or about 1,500 miles from home, the weather became so hot that they could not sleep comfortably in their cabins below, and passed the nights on deck; the sight of the flying fish seemed specially to strike them, flying sometimes in the air for a distance of about a chain and a half and then diving again into the sea …. the passengers on board the ship numbered nearly 700, chiefly English, but some from Germany and others from Russia.’

By the time the Potosi reached Adelaide half the passengers had already disembarked, including the Ascott lads, who had reached their destination at Perth. The following June, Rev. Yorke reported, ‘Four other Ascott youths, James and Albert Weaver, George White and Henry Pratley, have sailed in the ship ‘Charlotte Padbury’, for Perth, Western Australia; also Thomas Ward and his newly wedded wife. Let us wish them all a prosperous voyage. With the others who have previously gone out from our Parish there will be quite a little Ascott colony settled in those remote parts. But there is an abundance of room for a very large population; the inhabited portions extend for about 350 miles in length and 200 miles in breadth (or nearly the entire size of England), but the whole population does not at present exceed 10,000 persons and thus many districts are very thinly peopled.’

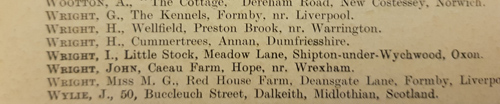

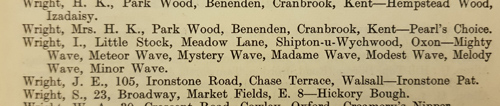

Brothers James and Albert Weaver had been born in Ascott and were the sons of a shoemaker, Charles. James was 20 and Albert 18 when they left to seek their fortunes abroad. George White, aged 22, was the stepbrother of Frederick White, who had already sailed for Perth, and eighteen-year-old Henry Pratley was the younger brother of Raymond Pratley, who had left at the same time as Frederick White. So it would appear that favourable reports had been winging their way across the world to family members in England. The Charlotte Padbury, which left London on 26th June 1881, was a clipper barque of 636 tons, significantly small in comparison to the Potosi. She was owned by Walter Padbury of Perth, Western Australia (see below), but had been built in Falmouth. Her Commander was Thomas Barber and on this particular voyage he had taken his wife with him. She had been a cabin passenger, together with one other, in what were reputed to be well-ventilated cabins. The saloon was said to be spacious, a bathroom was included and the accommodation was declared superior. The number of steerage passengers, including the six from Ascott, was 24.

In the August issue of the Deanery, Rev. Yorke had reassuring news to impart: ‘The painful rumour that was spread abroad in the Parish, early in last month, of the total loss of the ship containing those who have lately left us for Australia, has happily proved to be unfounded: the owners, Messrs. MacDonald, have written to say that they have every reason to believe that the vessel is quite safe and pursuing her voyage.’

The December issue of the Deanery reported that, ‘Tidings have come of the safe arrival of the ship ‘Charlotte Padbury’ at Perth, Western Australia, on September 18th, conveying, amongst other passengers, James and Albert Weaver, George White, Henry Pratley, Thomas Ward and his bride (formerly Sarah Ann Hone), all from Ascott. The voyage occupied about 12 weeks.’ A newspaper sent to the Vicar from Perth, announcing their arrival, states that it was ‘a pleasant and welcome sight to see the fresh English faces of the emigrants, healthy looking and cleanly dressed.’

The March 1882 Deanery reported: ‘The following is an extract from a letter, lately received from one of the Ascott youths [probably Albert Weaver] who emigrated to Western Australia in the summer of last year: he was a Church bell-ringer and also one of our best cricketers:-

Swan Bridge, December 26th, 1881.

Christmas has come again and found me a long way from the post I occupied, last year, that of ringing the old Church Bell. I am now in the burning sun of our midsummer, while you, probably, are in a land of snow and ice. We travelled up into the bush from Perth with a team, and we felt it rather strange having to roll ourselves up in our blankets and sleep under the wagon; after 5 days we reached our destination but we found ourselves in a very rough place and resolved to leave it as soon as possible. I left the work and took to my trade again (shoemaking) and am doing capital well, but I must tell you that if one comes out here they must not care how they live, or they had better stay at home, though a man can earn more money here, but I would not advise anyone to come out here for I shall not stay for long.”

Four months later there was news of the Townsend family. ‘Tidings have lately come from Mrs Townsend’s three sons, in Western Australia: they seem to be doing well, but the Colony has suffered, in the past summer, from a terrible drought such as has not been known there for 10 years: the pastures have been dried up, and the sheep, cattle and horses have been dying by the hundreds. Mr James Townsend, who left England shortly before his lamented father’s death, in 1876, has married and settled down in Geraldton, in Champion Bay, almost 300 miles north of Perth; he kindly signifies that he will shortly send a few notes giving some account of the country, which may appear in our Magazine. Alfred has gone several hundred miles higher up into the bush, where a white man is rarely seen, near to the pearl fisheries: a Church is not to be found in his district, he seems to feel the want very much, Edwin is with Mr Padbury, in the neighbourhood of Perth.’

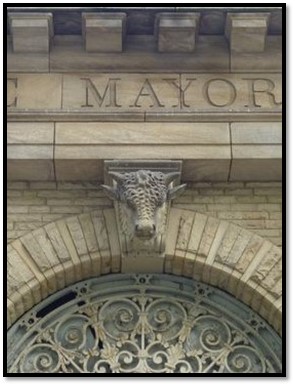

WaIter Padbury was a significant figure in Western Australia history. He was born in 1820 at Stonesfield, Oxfordshire, the second son of a small farmer. He emigrated with his father to Western Australia in 1830, intending to send for the rest of the family once they were established. Unfortunately within five months Walter’s father died, and a couple whom his father hoped would look after Walter took his money and disappeared. Walter found work around Perth, eventually becoming a shepherd, until, aged 22, he took to fencing, shearing and droving. He acquired his own stock, which he sold at profit, and eventually secured enough money to bring the rest of his family to join him. In 1845 he married 18-year-old Charlotte Nairn and established a butchery in Perth. He became a property owner, built a flour mill and was very good to his employees. Eventually he went into shipping (his ship, the Charlotte Padbury, was evidently named for his wife) and set up with William Thorley Loton as general store keepers in Perth and Guildford. He was very active in public affairs, long associated with the Agricultural Society; he became a justice of the peace and mayor. He contributed generously to the church, to the establishment of children’s homes, hospitals, to the poor and other charities. He died in 1907, and after legacies to relations and friends, left about £90,000 to be divided amongst named charities.

Padbury had also been a great letter writer and at the end of 1882 appears to have written to Rev. Yorke. ‘Our Magazine obtains a wide circulation: it has readers in America, South Africa and Western Australia. Mr W. Padbury has written from Perth, in the last named Colony, drawing attention to the letter of an emigrant from Ascott published in our parish notes of March last. He does not dispute the facts stated therein, but writes:- “There is ample room in any of these Australian Colonies and New Zealand for half the population of England: but they must not come here with the notion that they can at once make a fortune, or jump into the shoes of those who have been here all their lives; if they are industrious and economical as a rule they will certainly do better than they can in England.” Mr Padbury adds statements of wages given, corresponding with those set forth on the first page of last month’s Magazine in Sydney, New South Wales. On the other side of the question it is only fair to consider the length of the voyage, extending at times, to over 100 days in reaching Perth; the extreme heat of the climate in Summer, and its liability to not infrequent droughts; also the separation from friends and acquaintance, the many hardships to be encountered and the like.’

There is some more evidence about the emigrants, which seems to suggest that mixed fortunes attended the Ascott lads. Of the Townsend family, the only additional information is about Edwin. He married Lucy Ann Drummond in 1887 but unfortunately died in 1900, only thirteen years later, aged 36. Both Raymond and Henry Pratley married in 1884, but nothing further is known. Albert and James Weaver also married in 1884. Albert married Charlotte Staples in Fremantle. They had at least one son, Charles George, born in 1889. Charlotte died in 1914 and Albert in 1938. James Weaver’s marriage to Sarah Hyde was very shortlived. She died the same year, aged only 18, and their son of three months, James Albert, died the following year. It would appear that James married again in 1888 and hopefully fortune then treated him more kindly.

Nothing further is known about Frederick White, but George White married Jane McGowan in 1884. Sadly fate was not kind to them either, since George died the following year aged only 26. However, it would appear that the oldest son of William James White, the Ascott blacksmith, and the brother of Frederick and George, had, like the eldest Townsend son, preceded his brothers to Perth. In 1879 he married Annie Coffin at Yatheroo and in the following years, they produced a family of four sons and three daughters. Three of their sons joined the Australian Expeditionary Force in the First World War. The eldest, George Eustace, named for his uncle who died the year that he was born, joined the Australian Army Medical Corps and served in Egypt. Bason, the youngest, perhaps fortunately for his mother’s peace of mind, was too young to leave Australia before the War ended. The second son, Cecil, married Ivy Derepas in Perth in 1915 and later, as a sergeant in the Australian Expeditionary Force, was shipped to England. On leave, whilst completing his training, he travelled to Ascott to see his father’s birthplace. Then in January 1919 he sent to his cousins, the White family living in Centuries House, copies of the photographs of Ascott which he had taken during his visit. His photographs will be reproduced in a future volume of Wychwoods History.

Wendy Pearse 2016