You are being watched!

An unusual feature of Milton is the scattering of small pieces of sculpture which adorn a number of properties throughout the village. We are never going to rival Florence in our sculptural adornment, but these little carvings illustrate a sometimes-overlooked theme in the history of the village. This article is firstly intended to provide a record of these items as interesting artefacts within the village and secondly is an attempt to put these sculptures into their historical context and to suggest what their origins may have been, because almost all have been relocated from now unknown original settings. If any of our readers have any information on the further history or origins of these sculptures the History Society would be delighted to hear from you. I must also say thank you to the owners of buildings who have provided information about their sculptures and allowed access to their properties to take photographs.

A PDF of this article is available here

Usually sculptures in small rural villages in the Cotswolds and elsewhere are to be found on and within the local parish church in the form of architectural ornament or funerary monuments. However, almost all the ones described here are scattered among the domestic buildings of Milton, that is unusual. Most of these survivors are a legacy of the presence of Alfred Groves and Sons in the village. Many are probably salvaged features from the demolition or restoration of other buildings in the region by Groves, or sample pieces undertaken by apprentices. There are other pieces of sculpture and ad hoc bits of carving inside a few properties within the village which are not on public view but are also a part of the legacy of Groves’ presence (figures 1 and 2), these seem to be the doodles of masons living locally. Groves was once a huge enterprise in the centre of Milton. The company provided masonry, timber and building skills to many projects throughout Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire including Oxford Colleges and St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Their heyday was in the second half of the 19th Century, and early 20th Century. An account of their history by Norman Frost appears in volumes 7, 8 and 9 (1992/93/94) of the Wychwoods History Society Journal.

Wooden figure of angel playing a woodwind instrument

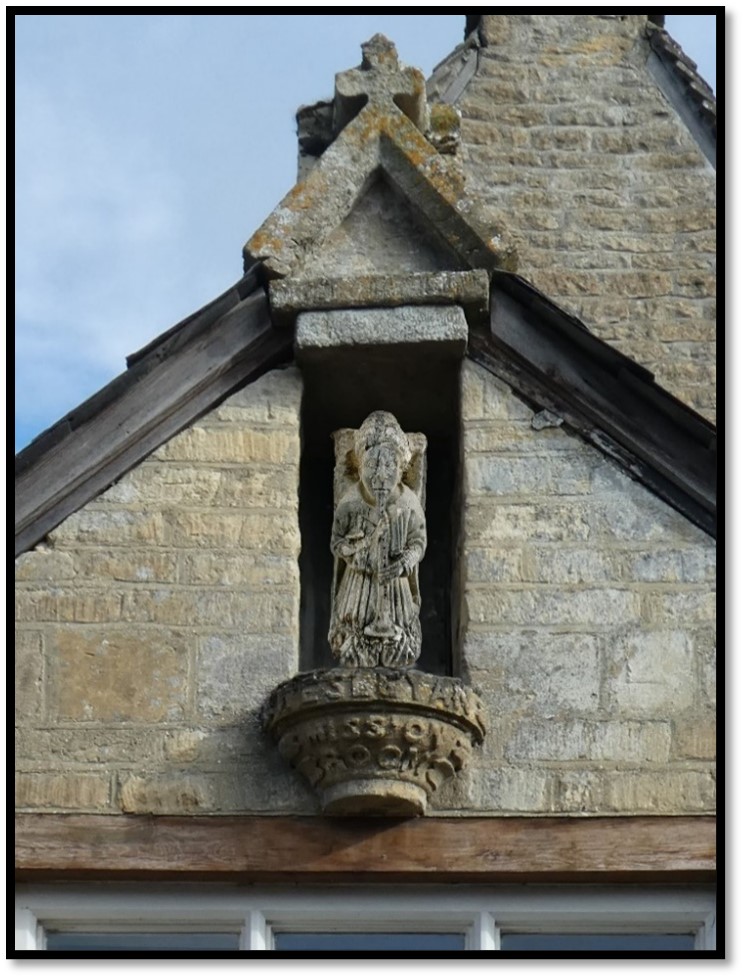

The oldest surviving figure sculpture in Milton is the wooden, probably oak, carving of a figure playing some sort of woodwind instrument. This instrument is sometimes identified as a shawm (figures 3 and 4). He has wings and is therefore an angel. Unfortunately, he is no longer on public view, but for a long time he occupied a niche on the front of the former Wesleyan Mission Room on Milton High Street. He is thought to date from the 15th Century.

He might have been a fixture in Milton for many years before he was given his own niche in this prominent location on the High Street sometime in the later 19th Century (figure 5). His time outdoors has taken its toll and he was taken down around 2006 and is now housed indoors. His origin is unknown, he almost certainly formed part of a decorative scheme of such figures in a religious setting, and it has been speculated that he may once have formed part of the decorations of nearby Bruern Abbey before it was dissolved by Henry VIII.

There is a strong tradition of such musical angels in churches in East Anglia and figure 6 shows one such from St Wendredas in March, Cambridgeshire. This is one of 118 figures of angels in this church. Similar figures appear in the church of St Mary the Virgin in Ewelme, Oxfordshire, a little closer to home.

There is of course a tradition of musical angels in European painting and sculpture from the middle ages and they also sometimes appear in secular settings. A distant cousin of our figure can be seen on La Maison d’Adam in Angers, France (figure 7), a late medieval house from 1491, and therefore of a similar age to our figure, just one of the many carved figures which decorate this French house.

Two stone heads on St Michael’s – a house on Milton High Street

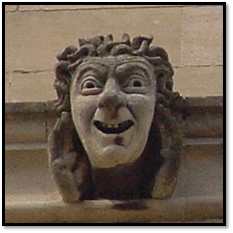

These two heads were not made for this location but have been repurposed from their original locations sometime in the late 19th Century when this property was probably upgraded. The uppermost grinning figure forms a corbel that supports the timber strut-work that now decorates this gable (figure 8). Strut-work of this type was becoming a popular architectural feature in the area towards the end of the 19th Century. He is much weathered and has the appearance of a gargoyle. Again, this figure may also have been salvaged from some church restoration undertaken by Groves. He is difficult to date, possibly 18th or early 19th Century. Such caricatures frequently decorate local churches, and many Oxford Colleges (figure 9) and one or the other may have been his original function.

The lower figure is a different sort of character (figure 10) and has the appearance of a portrait. There is evidence of a moustache extending to bushy sideburns, and his shoulders appear to be adorned with toga-like drapery. These details date him to the early to mid-19th Century. The toga draped busts of British worthies of the Georgian and Victorian era decorate many a provincial town hall or art gallery, not to mention the Houses of Parliament. Such portrait busts were also used to decorate the façade of public buildings. The heads of Shakespeare and Garrick feature on many a theatre façade, and famous artists feature on municipal galleries. There are quite a few for example on the National Portrait Gallery. Figure 11 shows one such figure that decorates a building in Bath. It would be nice to know who our character is, but his rather eroded and decrepit state makes this a tricky task.

Female head on Dashwood House

The head of a young woman projects from the wall above the doorway to Dashwood House on Shipton Road (figure 12). The building dates from the late 19th Century, but the stone head of the young lady is from elsewhere, and possibly 18th or early 19th Century. She was probably carved as either a supportive corbel or as a carved termination of a drip hood such as are frequently seen on English parish churches. Rather weathered examples can be seen on the nearby Church of St Mary in Shipton, but a close relation of our girl can be found as a decorative termination to a drip hood to a window on St Edwards in Stow-on-the-Wold, this was probably the original intended function of our young lady.

Bulls Head, Milton High Street

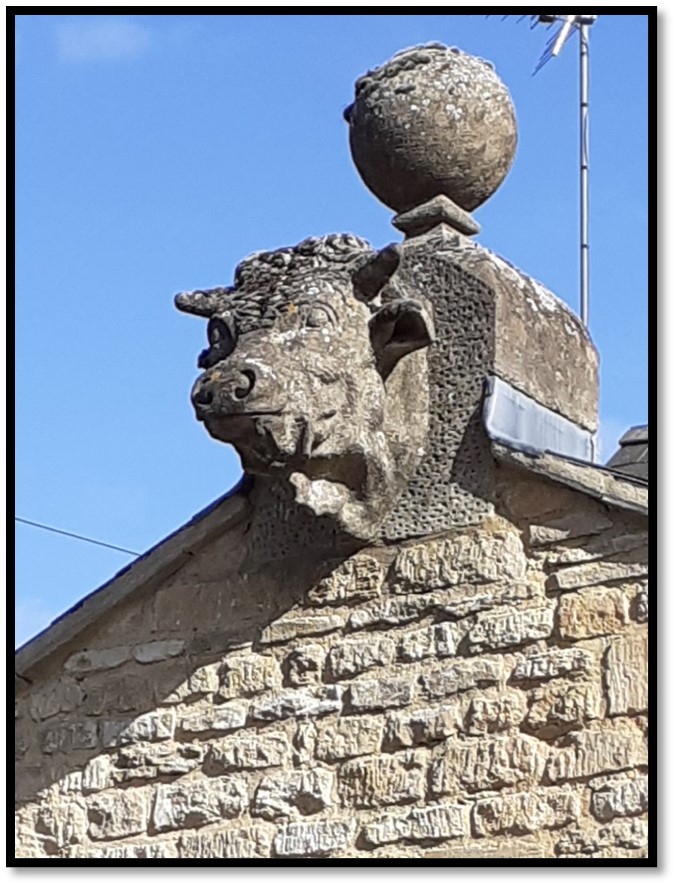

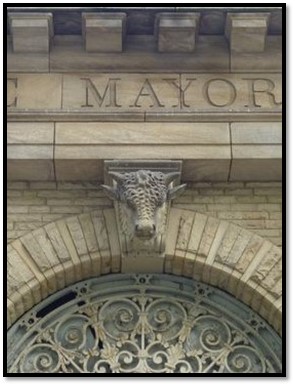

A prominent piece of sculpture on the High Street is the carved bull’s head topped by a ball finial atop the gable of what is now the High Street entrance to the small development of Harman’s Court (figure 14). The single-story building is modern rebuild of a similar structure on the site that once served as a butcher’s shop by the name of Harman’s. The back of the premises once housed an abattoir. The bull’s head was in situ on the original building and was saved and re-mounted on the replacement building which is now a domestic residence. The building opposite was once a pub called The Butcher’s Arms. Our bull now serves as an important reminder of this now hidden past. Nonetheless, he is also a refugee from some other location, as it is highly unlikely that a small village butchery would have commissioned such a statement piece of sculpture. Again, the hand of Groves is seen in the re-homing of the bull’s head here. He probably dates from the mid-19th Century and would have once adorned some Victorian Market Hall. Similar examples can be seen on Victorian Market Halls in many larger British cities. Figure 15 shows an example from the former Smithfield Market in Manchester.

Boar’s Head, Groves Industrial Estate

A companion to the head of the bull can be found atop a gable on one of the buildings just behind Groves’ hardware store. It is the head of a boar, perched high on this gable, and he is difficult to see. However, he is also a rehomed piece of stone carving from a now unknown location, but possibly also from a former market hall.

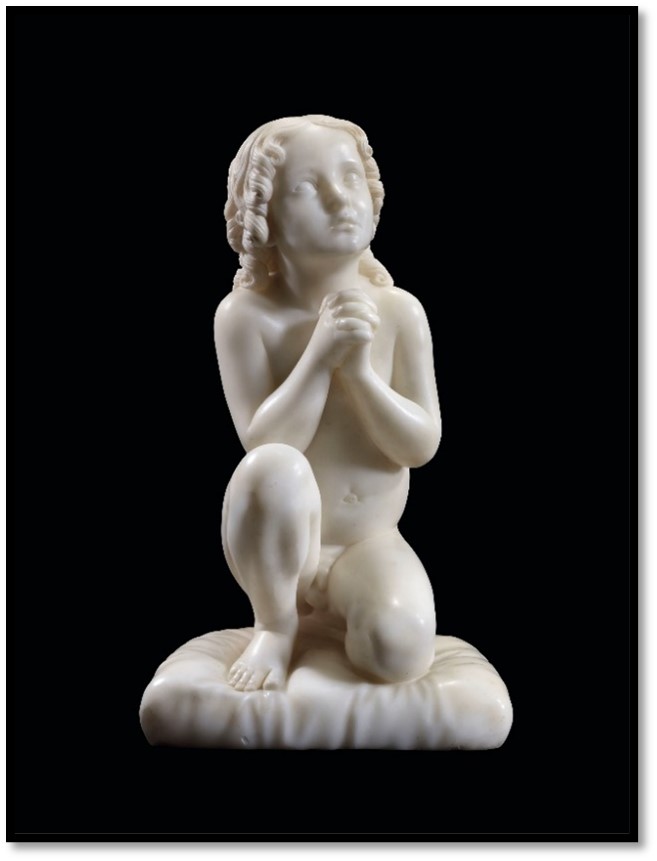

Kneeling Praying Figure, Brasenose, Shipton Road

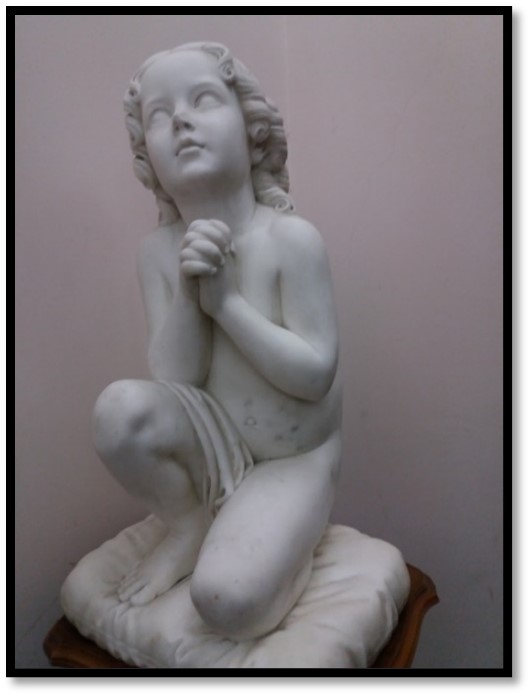

This surprising figure sits on a pierced gothic plinth sited above a door canopy on Brasenose, a cottage on Shipton Road. It shows a kneeling praying figure with face raised heavenwards (figure 17). The figure is not well detailed partly through weathering and partly by the design of the unknown sculptor. He is a rather simplified copy of a figure originally known as the Bambino Inginocchiato Orante (Kneeling Child Praying) originally conceived by the Florentine sculptor Luigi Pampaloni (1791-1847). Pampaloni first executed the figure in plaster in 1826 (Accademia Belle Arte, Florence). It was a commission for a funerary monument to the daughter of the Russian noblewoman Anna Potocki. The original design had the unclothed boy kneeling on a cushion (figure 18).

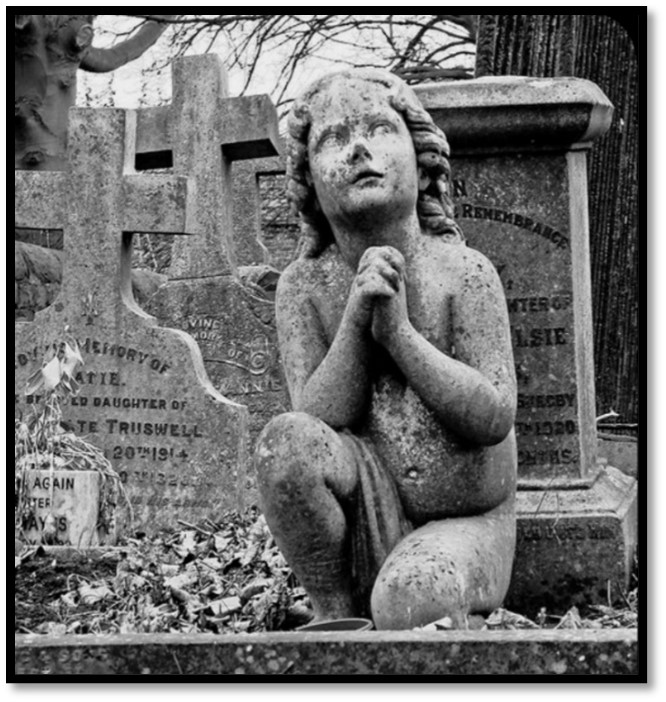

The figure became an enormous success and subsequently Pampaloni and his assistants executed many copies in marble that can be found in museums and graveyards across Europe. Whilst the original praying boy was conceived as a nude statue the concept was taken up by many other sculptors throughout the 19th century. In many of these variants his modesty was often preserved by the addition of a discreet piece of cloth draped over his right leg (figure 19). This is the version copied in the Milton figure. There are now probably thousands of versions of this figure throughout the world, many featuring as funerary monuments to young children. The one illustrated here is in the churchyard of St John the Baptist in Tibshelf, Derbyshire from the early 20th Century (figure 20). Our modest figure, from the late 19th or early 20th Century, was probably also originally intended to decorate a funerary memorial. This is reinforced by the gothic base containing a candle, a symbol of the brevity and fragility of life. However, whose memorial this was intended to be and how it ended up as a decoration to this door canopy we might never know.

Sculptural collages on Holmleigh, Jubilee Lane.

The next item is what might be described as a sculptural collage of various carved fragments inserted into each gable end of Holmleigh on Jubilee Lane. The house bears the date 1869 and was almost certainly built by Groves. The fragments are obviously from different sources, and from different types of stone. Many of the fragments seem to have funerary associations and were perhaps intended to form parts of gravestones. The composition on the right-hand gable contains the head of a cherub. Similar cherub heads can be seen on gravestones in Ascott and Shipton Churchyards, and a rather faded one appears carved above the doorway to Stone Porch, a house on the High Street. Beneath the cherub is a carving of a weeping willow arching over a cross and some tombstones. The weeping willow is another common motif on Victorian gravestones for obvious reasons, though I have not been able to find any on local gravestones. The assemblage includes some gothic arches, placed horizontally, and vertically in a rather whimsical composition. These fragments are again almost certainly salvaged pieces from demolition jobs or renovation jobs, or even perhaps apprentice pieces done by younger masons working for Groves.

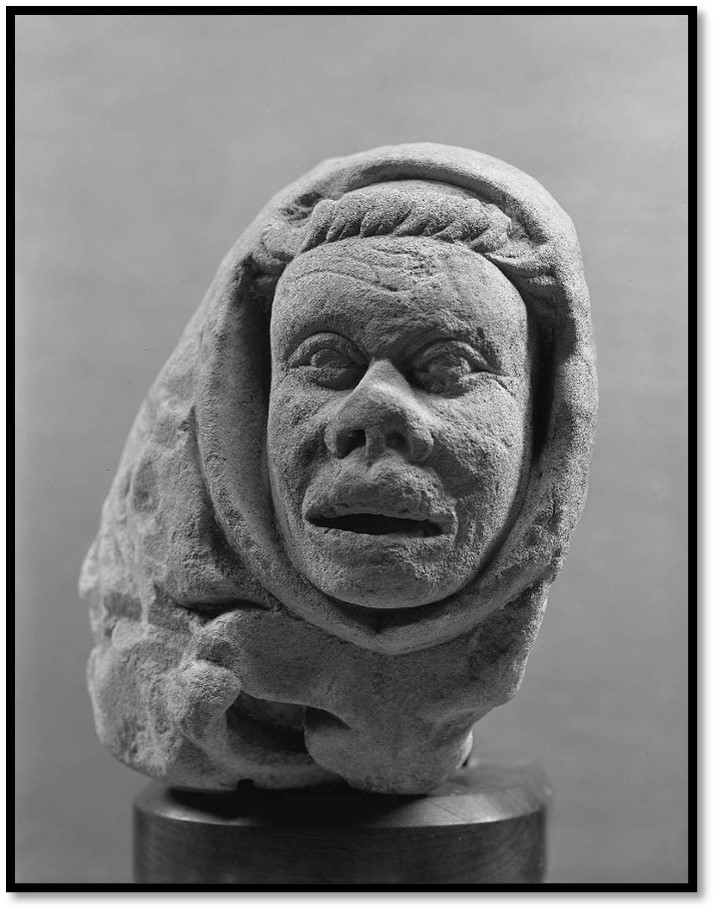

Hooded figure on Forest Gate (Formerly Frogmore House)

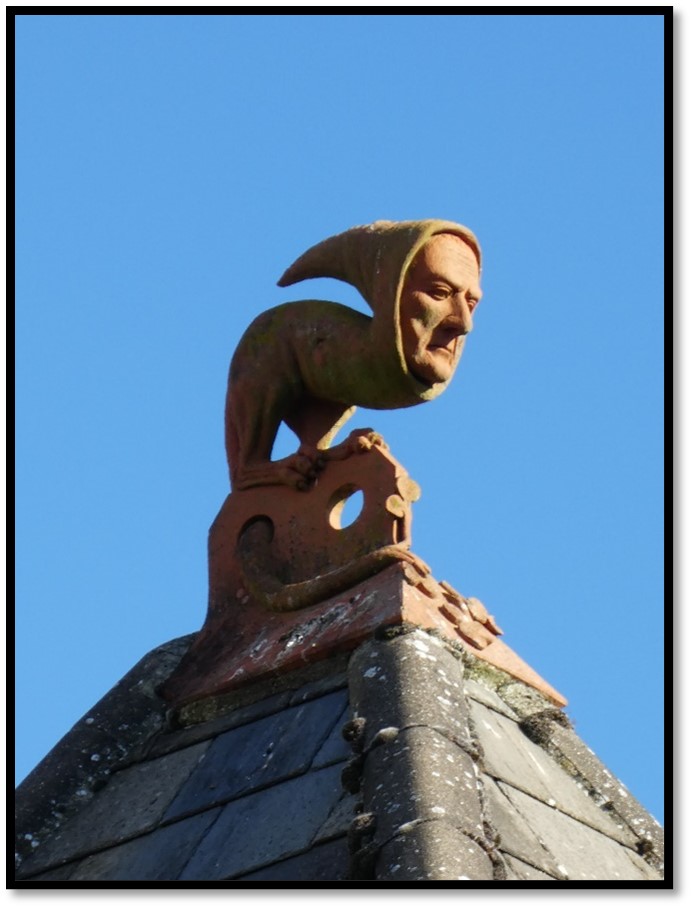

Our next sculpture comes from a grand late Victorian villa on Frog Lane (figure 23), formerly known as Frogmore House but now called Forest Gate. The house dates from the very early 20th Century and is quite a statement property with its multiple gables and large stained-glass windows to the main façade. Topping the pyramidal roof to one of the front bays is a cowled figure made from terracotta. He is the only sculpture in our study to occupy his original intended location. Figural terminations to roof lines were common on some of the grander houses of the later 19th century, dragons being a particular favourite. There is a terracotta dragon on one of the gables to the nearby Woodhill, the Sands (originally known as Holmleigh) which is of about the same date. This figure, half man half beast – note the claw like feet – is a re-imagining of the many hybrid-creatures that decorate churches and cathedrals and colleges up and down the country (figure 24). His face, however, is no caricature but has the look of a sensitively modelled portrait; one assumes he is the person who originally had the property built, some further research is needed here.

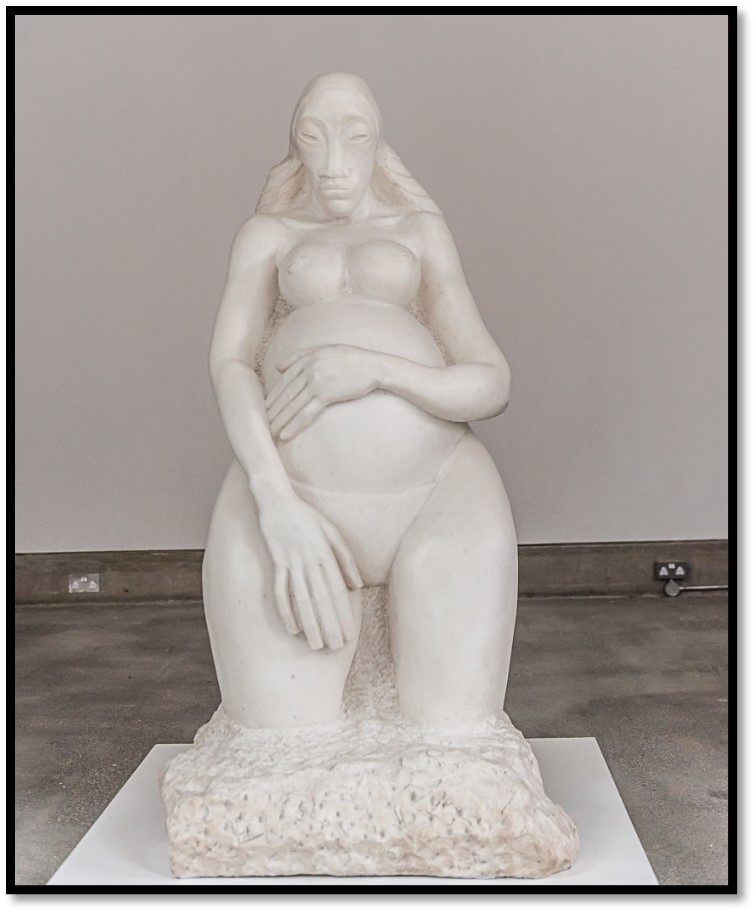

Mother and Child by Constantine A Smith, Broadstone, Green Lane

The carving of a Mother and Child sitting in front of a house on Green Lane is something apart from most of the other sculptures in this article: it is freestanding, rather than attached to a building, and it is the first piece of “modern” sculpture to appear in the village. It was commissioned by a former owner of Broadstone, and executed by the sculptor Constantine A Smith, about whom little is known other than that he was Cheshire based and active in the 1960s and 1970s. This sculpture dates from circa 1970. It shows a naked woman sitting cross legged on the ground cradling a young child who clings to her, burying its face in her body in a naturalistic way, though in other ways this carving might be described at expressionistic rather than naturalistic. The sculptor has exaggerated the size of hands and feet and generally simplified the swollen forms of the figure and stylised the facial features of the woman, perhaps in an attempt to express the fecundity of motherhood. The image of the mother and child has a long and daunting history in Western art, including the many images of the Madonna and Child, and even with the decline of the church as a patron of such works, sculptors have continued to tackle this iconic subject. This figure is a secular version of the subject, a kind of Earth Mother, naked and seated almost directly on the ground. The style can be described as broadly modernist, owing much to the revival of the technique of direct carving (working directly in stone rather than preparing a model in clay or plaster to translate to stone) as promoted by sculptors such as Eric Gill and Jacob Epstein in the early decades of the 20th Century. The sculptor has left the texture of his toothed chisel very evident in the carved surfaces. If we want a very direct precursor for this Mother and Child we need look no further than the figure of Genesis by Jacob Epstein from 1931 (figure 26), a sculpture that was hugely controversial in its day.

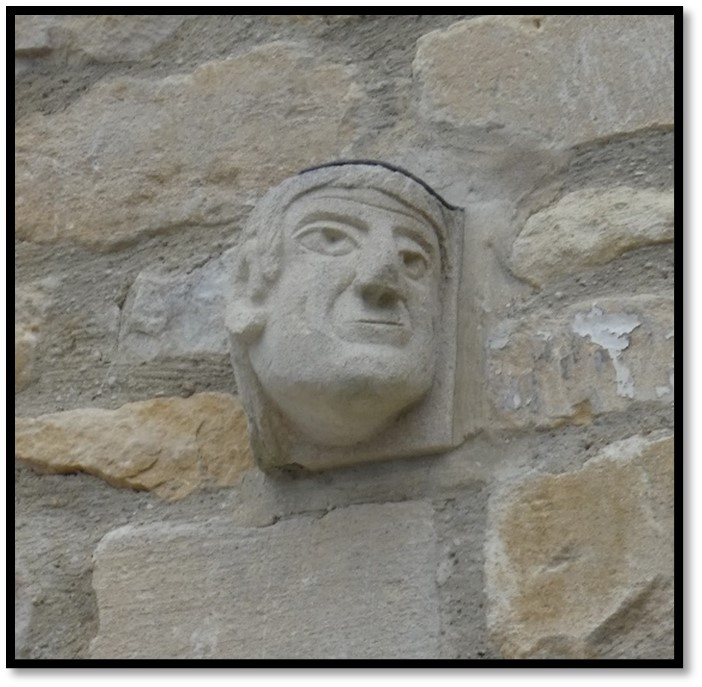

Carved Head of Dr Who, façade of Groves Hardware Store, Shipton Road.

Our final head appears after a gap of over a hundred years since the last head was added to the village (Forest Gate), so represents a renewal of this Milton tradition. He projects from the upper story of Groves new hardware store which was re-built after a fire in 2014. He is also a sculpture that was originally intended for another location, and was one of a number of heads commissioned as part of a Groves’ maintenance project on the medieval church of Holy Trinity in Bledlow.

However, for reasons unknown this head was not used. The other heads for this church included the four members of the Beatles and the local lord of the manor Lord Carrington. The head featured on Groves hardware store is intended to be the actor Patrick Troughton as Doctor Who. He was again to be a figure terminating a drip hood. And so the tradition continues.

Further Reading

Michael Rimmer: The Angel Roofs of East Anglia: Unseen Masterpieces of the Middle Ages, 2015.

The volumes in the Public Sculpture of Britain series published by Liverpool University Press since 1997

Benedict Read: Victorian Sculpture, Yale University Press, 1982

Maria Teresa Sorrenti: Per il collezionismo reggino dell’800. Il “Putto orante” della Biblioteca “Pietro De Nava” di Reggio Calabria, nd.

Picture credits

All images copyright of the Wychwoods Local History Society except:-

Fig 6 – courtesy of Lynne Jenkins

Fig 1 and 2 – courtesy Peter Bradford

Fig 15 – courtesy Manchester Evening News

Fig 18 – courtesy Sotheby’s

Fig 19 – courtesy of the Biblioteca Pietro de Nava, Reggio Calabria

Fig 24 – courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts Boston

Fig 26 – courtesy of Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester