Here is an extended piece by Dorothy Brookes, taken from the WLHS Journal No. 7 (1992). We republish it here as part of an occasional series celebrating the work of the Society over time. (A PDF of the article can be found here).

I was born Dorothy Mary Coombes in 1911 in a small cottage, the last in a row of stone-built houses called Blenheim Cottages erected on land known as ‘manorial waste’ alongside the Burford Road. The top three were much older than the others: ours, ‘Top House’, the one nearest Burford, had a stone staircase. None of them had back doors. Farther down the road there was a common wash-house and drying ground. The cottages faced west and from their tiny bedroom windows could be seen Icomb Roundhouse, Stow-on-the-Wold and, away in the distance, Batsford Park. Tiny gardens and a rough pathway separated the cottages from the road which went up the hill to Burford or downhill through Shipton village, past the railway station and then on to Chipping Norton.

My mother always said that history unfolded itself on the Burford Road. There was no railway at Burford so people from there had to travel the four miles over the Downs to Shipton Station. There were carriages from the big houses, carters from the farms with their teams and huge wagons loaded with corn, cattle being driven, a horse-drawn bus and a few people on foot.

When I was three years old we moved just down the road to a better cottage. My father made many journeys to the new home with a truck he had made, my brother and sister helping him each time to push the load while I rode on top as I was the youngest. Mother scrubbed out as each small room became empty. A new tenant would make a thorough inspection of the vacant house and report to the neighbours if it had been left dirty.

The new house was a `back-to-back’, ours facing the west and the Burford Road like the one we had left, the back tenant facing east with their garden path going into a small lane. It was a much nicer house than the old one; there was a good garden with a pig sty, a good shed and our own lavvy’. But it had its drawbacks: there was no pump, so water had to be fetched from the stand-pipe some distance away. When it rained hard my mother had to stand at the door with a broom to turn away the water that cascaded madly down the steps. However, enough rainwater could be collected in a huge tub for washing the clothes, ourselves and for boiling the pig-swill.

I am told that the day I was three years old, I demanded a clean ‘pinny’ and a note for the teacher as I was now old enough to go to school. It seems that at two years old I had followed my sister and brother the mile to school and I vividly remember my mother snatching me away from the wallboard

where I was making an effort at writing my name. I was scolded all the way home with Mother saying ‘You shall go the day you are three my girl, I’ll have no more of this worry’. And go I did, although I must confess I don’t remember that day.

The Great War had started on August 4th of that year and our dad had volunteered for service on September 5th. My mother told us of the day he left home in his best suit to catch the train to Oxford. Here he enlisted in the 2/4th Oxon. and Bucks. Light Infantry. After a few weeks’ training and embarkation leave he was soon en route for France. It was along time before we saw him again and each night Mother led us, her three children, in prayer for his safe return. One night I was watching her brush and comb her lovely long hair when she said ‘It’s moonlight, the same moon that is shining on your dad. I wonder where he is tonight?’ We soon found out, for in a few hours’ time there was a shout from the garden of ‘Mother, open the door!’

Mother lit the candle and, carrying it downstairs, opened the door to a weary, muddy and pack-laden soldier. In a very short while she had our dad into clean clothes and, sitting by a blazing fire over a cup of strong tea, he told us how a few days’ leave had been granted following a terrible battle. A troop train had brought the soldiers from the Channel boat at Dover, up to London and then down to Oxford. From there, there had been no further transport. The men could either sleep on the platform or find their own way home; some lived in Oxford but others out in the villages.

Dad and his companion, a young man from Taynton, had walked to Shipton. The young man had come Shipton way to see Dad indoors and then had the long, cold walk over the Downs to his own home at Taynton. While Dad was at home he helped Mother with the garden and mended our shoes and boots. Mother ironed his uniform to kill the many fleas he had brought back with him, arid then left us at Granny’s while she went to the station to see him off again. In a few days’ time she took us to stay at Chippenham with her brother Walter Longshaw and his four children. We lived there for almost a year.

I was six when we returned home – too young to know anything of war? Our schoolmaster didn’t think so. There was no radio or television in those days, but Mr Strong read the war reports to us from his newspaper. He told us when local young men were killed in action and who was badly wounded; we were taught to sing patriotic songs and to hate the Kaiser and his people. None of the schoolchildren had ever seen the sea but we were taught that the navy was playing a vital role in the defence of our island. To illustrate this, my dad sent me a Navy ABC for Little Britons. I took this book to school many times and have it to this day.

The way to school led through the churchyard. One morning I had raced ahead of my brother and sister and turned the corner into the narrow path. There, leaning against the wall was a familiar figure – it was ‘our Dad’. He had travelled down on the first available train from Oxford and was waiting near the school to see his ‘mites’ before walking the last mile home. The schoolmaster met him too and said that we children could go home. We heard that he had been awarded the DCM and were very proud to read the following week in the Oxford Times:-

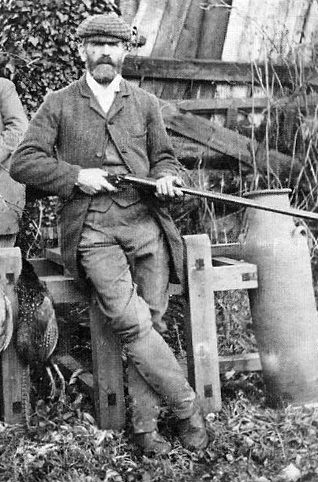

Lance-Corporal T.T. Coombes of the 2/4th Oxford and Bucks. Light Infantry has been awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for Auspicious Gallantry.

When an enemy torpedo knccked a man over the parapet severely wounding him, Coombes went out in full view of the enemy at 150 yards range and lifted the man back into the trenches. Lance-Corporal Coombes is an Oxfordshire man – his home being at Shipton under Wychwood.

We were soon to hear that he had been promoted to the rank of Sergeant. Later I remember the lovely Easter egg Dad sent us from Eastbourne, where he was recovering from burns from a discharged Very pistol. My brother saved most of his share to give to Mother the next Sunday. At times, food was not very plentiful but Donald never started his dinner until he was sure that ‘our Mam’ had hers on the table. He helped her in the garden, ran errands, cleaned the shoes and knives and was generally the ‘man of the house’. He was still only nine when Dad came home from active service. The schoolmaster told us about the coming Armistice and explained what it was. We expected Dad to come at once but of course this was not to be for a while. There were great celebrations in the village and Mother took us to Oxford to see the victory parade. I remember the decorated trellis arches and Dad waving to us as he marched by.

Eventually Dad resumed his work as a stonemason at Groves’ but, once home in the evening and in by the fire, he did not want to go out. He slept badly, haunted by the spectres of his young comrades dying in the mud and filth of Flanders, of the countless women and little children fleeing before the battles, the many screaming horses and cattle and miles of the cruel barbed wire that tore at flesh and clothes. I heard Dad say ‘The man who invented barbed wire should have been hanged with it’. The world ‘Fit for Heroes’ to live in proved not to be so.

Before long, men and boys who had been feted and cheered on their return from France were roaming the countryside looking for work. They often called at our house for hot water, tea, bread and cheese or perhaps an old pair of shoes or a jacket. Homelessness is no new thing: some of these men were on the road for years, and soon whole families were tramping, making their way to Northleach or Chipping Norton workhouse. There were hard hills to climb to get to either of these places where the men were expected to work for their supper. This may seem practical to those who have never known poverty, but these people were hungry, cold and ill-clad against the weather. They were in no shape to do much wood-chopping or scrubbing. No wonder they preferred to find a dry barn in which to bed down for the night.

Once a month there was a cattle sale down in the village; the sale ground was where the Bowls Club now have their green. Most of the cattle drovers were men who ‘lived rough’; they started early in the morning bringing the cattle in from neighbouring farms. Some came from villages many miles away: we could hear cows and sheep coming over the hill from Burford: not much time was wasted getting ready for school on sale day. Plenty of help was needed with the droving once the animals got near the village.

With my friends I stood at road junctions and open gateways to prevent the awkward cows straying off the road. At dinnertime we helped drive animals up the Burford road, very reluctant to go in to our dinner which Mother had cooling on the plates so that we could get quickly back down to the sale where we mingled with the grown-ups until the second bell for school.

We went back again after school, and this time helped a drover take cattle to the crossroads on the Downs. These men were paid a few shillings for this work and they usually gave a penny to any young child who would go up the hill with them. At Fulbrook, school-children would be waiting there to carry on to Burford. This continued until the cattle reached their new home, often miles out over the Cotswold Hills. From these huge farms, corn was brought to the mill at Shipton Station.

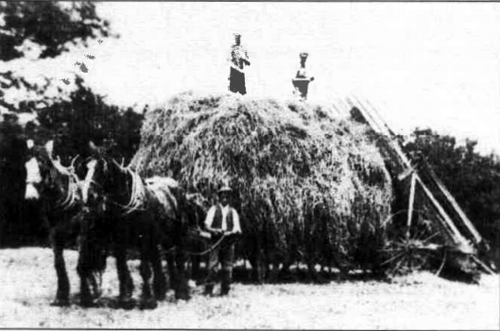

The carters had to make an early start and usually got to Shipton as we were ready for school. Their wagons were piled high with great loads of corn, and each drawn by a team of enormous but very gentle shire horses. The horses were decked out in well-shone brasses and some wore little caps on their ears. The wagoner had a ‘bolton’ of straw he could sell to provide his dinner money; it went to the first pig-keeper who had a shilling to spare.

We school-children followed the wagons down the street, hanging on to the tail-board and lifting our feet off the ground, thus getting a ride for a few yards. Envious school-mates would soon cry ‘whip behind’ and the wagoner would grin and curl his whip over his shoulder, trying to tickle someone’s ears. Later in the day the wagons had to make the long journey back to their farms. I was very friendly with one of the carters and instead of riding on the wagon he would walk up the hill towards Burford chatting to me. He wanted to hear bits about the world we had learnt at geography lessons and said he wished he had got a bit of learning. He liked to hear the recitations and songs and would make the cart horses stand until he had heard the last verse.

The horse-drawn bus made regular trips to Shipton Station to meet the trains. It came from Burford, picking up passengers from Fulbrook and the top end of Shipton on the way. The coachman was fond of ale and often stopped at the Red Horse too long so prudent passengers alighted here and walked the last quarter mile to the station. The once-talked-of branch line to Burford was never built although it was mentioned on the deeds of a cottage my father once owned as it might have gone through that cottage garden.

Other vehicles came up and down the ‘Turnpike’ (now the A361), mostly horse-drawn. There were the gaily-painted caravans of the fair people who came to the village twice a year and put up roundabouts, swinging-boats and stalls. The women folk went round the houses with baskets of pegs and cottons; if you bought from them you had a lucky face; should you refuse, calamity or sudden death were forecast. We knew one of the men with the fair as he came into the village in spring and autumn to sweep the cottage chimneys.

One year there was a constant stream of Foden lorries through the village, all heavily laden on the southbound journey, with their loads hidden under tarpaulins. We wondered what they were and finally found out that surplus shells and ammunition from the war were being taken to Bristol to be dumped in the Channel. These lorries had to pass close to our gate and one day the road surface gave way and the wheel sank in, firmly stuck in the clay. My mother went out to see what was the matter and made cocoa for the man and boy while it was decided what to do

. In those days the only telephone in the village was at the Post Office, so a telegram was sent for help but it was three days before a relief with hauling tackle arrived, during which time the lorry had sunk even deeper into the clay. The driver slept in the cab and the boy in our wash-house and Mother helped with the food situation: the driver did have a tin of bully and some bread with him. The village children swarmed around to look at the shells and we wondered if we might get blown to bits in our beds.

The first rescue attempt was a wash-out; the thick steel rope broke and bits flew far and wide: it was lucky no-one watching was hurt. We children were sorry to see ‘our Foden’ finally rescued as it had been quite an exciting few days. The Fodens were steam wagons and ran on coal: the driver gave Mother a bit of coal for her kindness.

Other events came along to claim our attention. Sparks from the chimney of the Foden belonging to Groves the builders set fire to a barn up the Station Road; the horse-drawn bus turned over and people were injured; a school-friend was impaled on the spiked railings outside the Baptist Chapel; one night a terrific gale brought many trees down, blocking roads and lanes; torrential rain or melting snow caused the River Evenlode to flood the meadows and Station Road so that we were sorry that the school wasn’t on the other side of the river.

On the whole though, school-days passed pleasantly enough, and it was soon time for those not lucky enough to go to Burford Grammar School to think about looking for work. The girls mostly went into domestic service and the boys either to the farms or, if they were lucky, to an apprenticeship to a carpenter or into the building trade. There were a variety of ways of getting to the Grammar School, mostly scholarships of one sort or another. Boys walked to Burford from the villages and those from Kingham came to Shipton on the train and then on by foot or bicycle.

The Girls’ Grammar School had only just been opened then (1922); previous to this, a favoured few who could afford the train fare went to Oxford with forgotten scholarships somehow brought out into daylight for these lucky ones.

My brother won a scholarship to Burford: I missed the exam because I caught the dreaded scarlet fever. No-one knew where I caught it as there was not another case in the district. It was contagious and, in those days often fatal, but my mother said she would nurse me at home as the nearest isolation hospital was many miles away at Reading. She faithfully carried out the strict rules laid down by the village Doctor and as a result I recovered and no-one else caught the complaint from me.

I got the rest of my education when and how I could, reading books considered too old for me, watching others and, later on, attending W.E.A. classes and taking full advantage of anything offered by the Women’s Institute and their wonderful Denman College.

But before that, there were changes at home. Dad bought Rock Cottage round the corner and we moved our bits and pieces to a much larger place. Mother got the pig to move by rattling his food bucket; not having been fed all day he was no trouble to get into his new home.

There was a lot of work to do on this old cottage but with Mother as labourer it soon became a good home. Dad dug stone from the garden to build the garden wall. This cottage had a tithe on it and after quite a battle with the powers-that-be Mother and I went to the Old Bailey in London and finally got it redeemed. It was many years before there was a water supply – I had left home long before that came about.

Reproduced from the WLHS Journal No.7 (1992)