It was with sadness the Wychwoods Local History Society learned of the passing of Dr Kate Tiller OBE.

Kate is remembered as a key supporter of the society in its early days. It was her enthusiasm for our project which encouraged the founding society members. Her advice and practical support meant we were able to acquire and develop skills to direct our research efforts fruitfully.

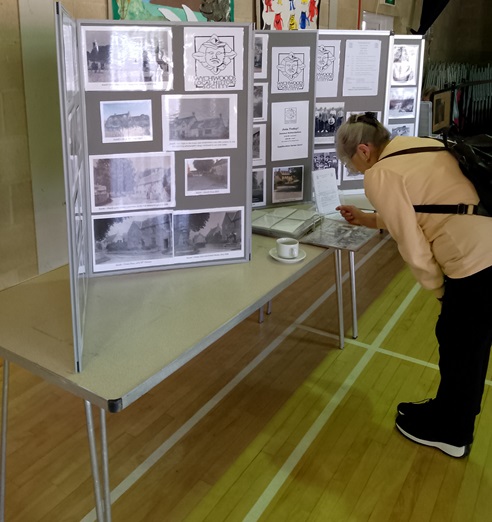

As Margaret Ware recorded in her review of the history of the society: “In January 1983 we found that the fund-raising members’ evening with wine and a ploughman’s supper had grown to a substantial exhibition and well over a hundred enthusiastic people crowded into Milton Village Hall.

Among the visitors was Dr Kate Tiller of the Oxford University Department for External Studies (as it was then) who congratulated us and offered to hold a series of evening classes in the Wychwoods on ‘Sources of Local History’, which duly started the following winter”.

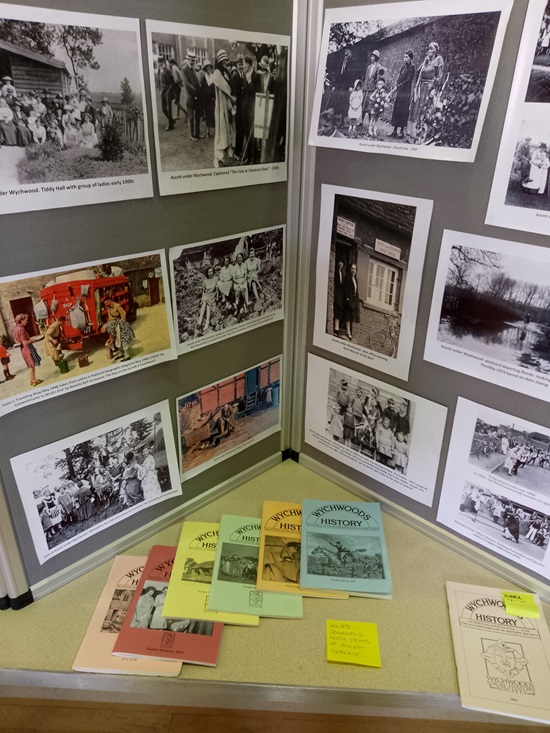

Largely because of the skills developed from these classes, our first journal, Wychwoods History No. 1 was published in May 1985. Kate wrote an appreciative preface for us. The journal proved extremely popular and was soon reprinted.

The Journal with Kate’s preface is available here to view or download.

We record the Kate’s passing with gratitude for the extraordinary support she offered, guiding a group of enthusiastic amateurs to achieve some professional research of lasting value.

A tribute by Geoffrey Thomas, Professor Emeritus of Kellogg College Oxford where Kate was a founding Fellow, is available here.