Our season of monthly talks continued with the visit of Sue Smith, who has made in-depth studies at Oxford University, of wartime Conscientious Objectors. She has examined the social profile of those who resisted wartime call-up and the public response to those who refused to fight.

The talk was again well attended with 30+ members, with an interesting Q&A session to round off another successful evening.

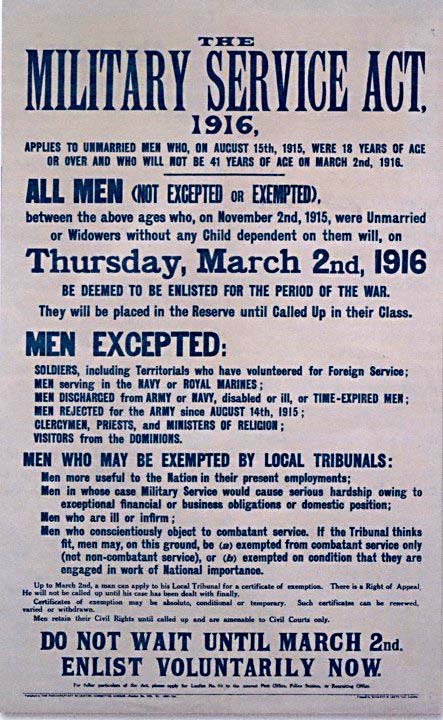

After two years of fighting in the Great War, with no end in sight, it became necessary by act of parliament to introduce conscription to maintain the fighting strength of the army. The Military Service Act was passed into law in January 2016.

With this introduction of universal conscription, everyone eligible was ‘deemed to be enlisted’. This meant that those who could not, or would not, join the Armed Forces were subject to a Military Tribunal which examined their case and delivered a verdict.

The Oxfordshire Tribunals, as throughout the country, comprised men who were established local figures, including local businessmen, farmers, manufacturers, and councillors. The tribunals would invariably include a representative of the Military, who exerted an influence on them. The military representative on the Oxford Military Service Tribunal was Lieutenant Walter Baldry, whom we learned was particularly unsympathetic.

Sue gave the example among many, of Alfred John Bishop who was an employee of the Clarendon Press, and loyal member of the Wesley Memorial Church congregation. He said at his Tribunal hearing in March 1916, ‘The commandment says thou shalt not kill, and killing in the sight of God is sinful.’ Bishop’s sincerity and good character was vouched for by the Rev. Brash, Minister of the church at the time.

But Baldry accused Bishop of being a “drinker and a gambler”. He also implied that the Rev Brash was either ill-informed about Bishop, or he was lying to protect him.

This tendency towards character assassination could be summarised in terms of the “cold footed brigade” vs. “the bigwigs”, but of course the problems which arose were far more complex in scope.

Who Were the Conscientious Objectors?

There were 18,000 registered conscientious objectors in the First World War. Of those, 6,000 went to prison because they felt it was wrong to participate in the war in any way. There were approximately 100 Conscientious Objectors in Oxfordshire. Most accepted work in the Royal Army Medical Corps, the Non-Combatant Corps, or other ambulance units such as the one organised by the Quakers.

Objections to fighting would in the main stem from deeply held religious persuasion, around the command “thou shalt not kill” and to “love thy neighbour”, but also on political grounds and in solidarity with fellow workers in other countries.

Sue reminded us that the percentage of the UK population which as institutionally or occasionally active in the church was far larger than in current times, and although the Church of England as the state religion could justify fighting to be absolutely appropriate in the face of demonstrable wrong, most Free Churches would have congregations with mixed feelings, and an active minority of individuals in all churches and denominations rejected the war outright as unbiblical and blasphemous.

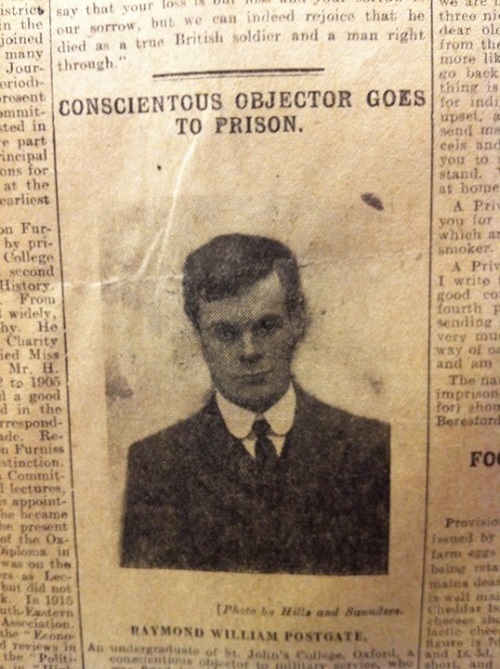

An example of an objector on political grounds was Raymond Postgate, who was a student at St John College in 1914. He was imprisoned in Oxford Gaol for two weeks in May 1916. In later life he worked as a left-wing journalist and set up the Good Food Guide.

The Response to Conscientious Objectors

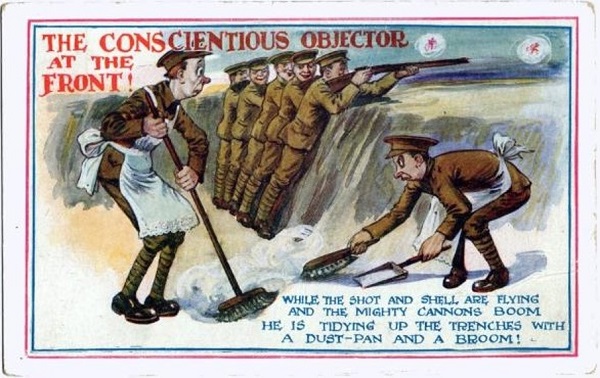

Because the right to conscientious objection was so new, and in the patriotic atmosphere of the First World War, it was widely unpopular with the public. It is no surprise therefore that conscientious objectors were mocked as cowards.

A general response, spread throughout the printed media and elsewhere, could be summed up in the phrase “What would become of England if all men were like you?”. Antagonism and debate was widespread, with regular questions in the House of Commons, and with a proliferation of cartoon mockery. However, the cause for those who came before the Tribunals was taken up by religious supporters and businessmen of faith.

Advocates for Conscientious Objectors

Among the several advocates in Oxford, Sue included Alderman J H Salter, a member of the Salter family who were Wesleyan Methodists, and had a boat building business.

Also mentioned was Charles Gore, as Bishop of Oxford, who wrote to the local and national papers demanding fair treatment for Conscientious Objectors. He tabled, introduced, and led a debate in the House of Lords on 5 May 1916 on this subject.

A manifesto appeared in the Oxford Chronicle in March 1916, signed by 11 church leaders protesting the activities of many Military Tribunals, advocating that sincerely held opinions should not be mocked. One of signatories was William Temple, who eventually became Archbishop of Canterbury in the 1940s

Sue gave us several other examples of supporters of Conscientious Objectors, and reflected on how, as the realities of the carnage of WW1 became known, opinions gradually changed over time. This change eventually resulted in legislation to guarantee the right of Conscientious Objectors to refuse to join the Armed Forces.

The extent of the change of opinion is reflected in the picture we saw of group of former Conscientious Objectors who had become Members of Parliament in later years. A case of the ‘cold footed brigade’ becoming ‘the bigwigs’?

About Sue Smith

Sue Smith has a Masters in Historical Studies from Oxford University. In particular she has studied resistance to war, how it is organised and supported, and whether it has an impact on public opinion.