by ALAN VICKERS

This article is also available as a PDF, downloadable here.

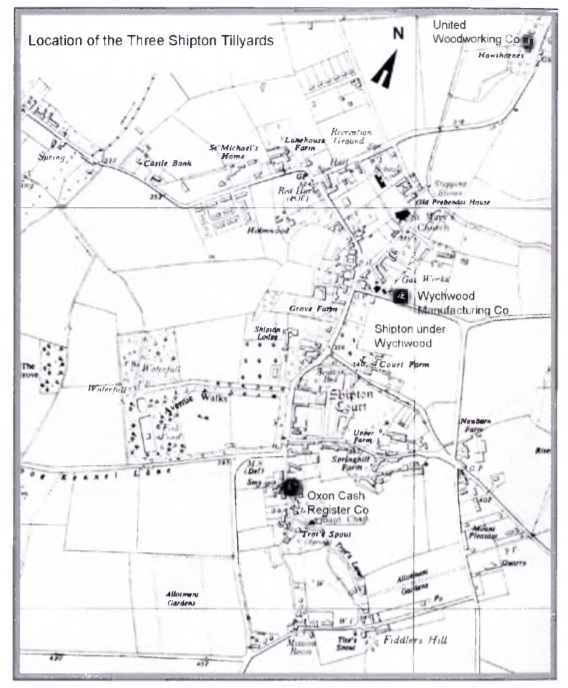

Wooden cash tills, usually with an opening on the top to accommodate a paper roll, were common in small shops throughout the country until about the 1970s. More often than not such cash tills came from workshops in Shipton under Wychwood. From the First World War until the late 1970s, the village housed three such businesses (see Map), which have now completely disappeared. This is the story of this local enterprise, which for so long was an important part of the village’s economy.

The first till manufacturing business was established by Alf Baylis just after the First World War. Alf Baylis had been raised in Shipton. His father was a railway signalman at Bruern and the family lived at 1 The Row next to the Red Horse public house.

Alf had a reputation as a bit of a “ladies’ man” who appreciated fast cars. He had learned the cash till construction business at Gledhills in Halifax (who in turn had copied from the National Cash Register Co) and brought Jimmy Wallace and Harry Crabtree with him from Halifax to work in his new business which traded in Upper High Street Shipton under the name of The Oxon Cash Register Co. Alf Baylis later lived at Wayside, Milton Road, Shipton.

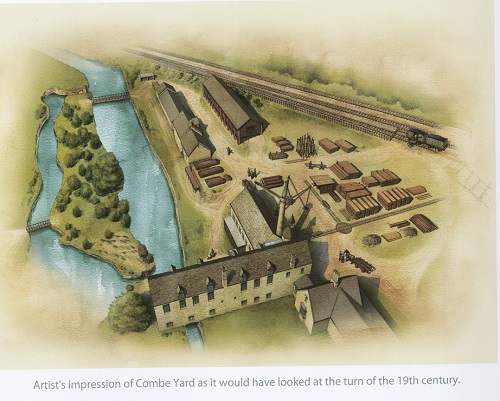

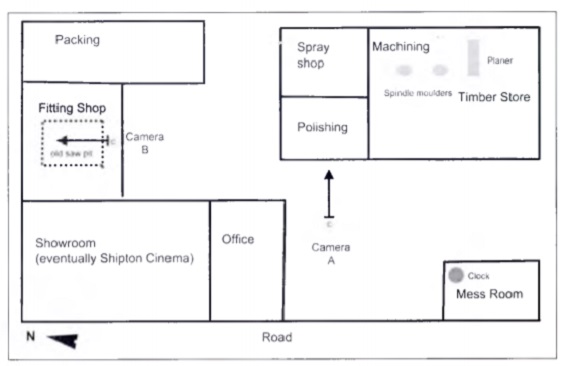

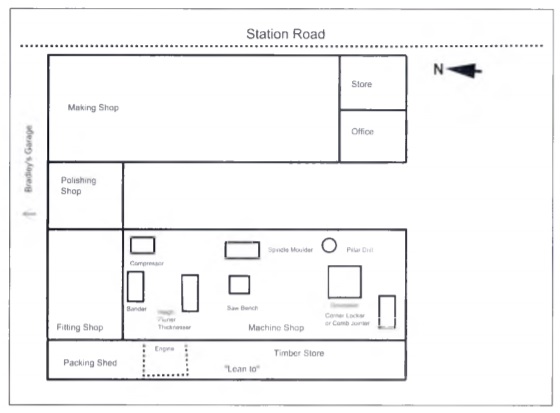

The site of Alf Baylis’s new business was a builder’s yard belonging to Shipton Court. It had been described as the “Estate Yard” in the sales catalogue of 1913 and as having a carpenter’s and painter’s shop, an engine shed and saw shed with saw pit. There were also hardware and timber stores. In total the area was given as occupying one rod and 11 perches. This reference to a “yard” encouraged the naming of the cash till manufacturing works as a “tillyard” and this was later applied to the other locations where cash tills were produced. Diagram 1 shows the layout from memory of the Baylis works (source Bob Coombes).

In 1919 Henry (Harry) Coombes and his second cousin William Edwin (Ted) Coombes joined Alf Baylis. They had worked at Groves, the Milton builders, before the First World War. By 1923 the relationship between the workforce and Alf Baylis had deteriorated, for example over clocking in procedures (the clock in question is shown in the mess room on Diagram 1) and possibly pressure to work on Sundays (both Harry and Ted were staunch church members and had been in the bell ringing team before the First World War – see Photo 3). One day in 1923 Alf Baylis lost his temper and told some of the men to leave.

The vicar of St Mary’s Shipton, the Reverend Nixon, helped the unemployed men set up their own business in the stable loft at the Vicarage but there were objections to men in working clothes being housed about the Vicarage. After some two years, premises were obtained in Station Road for the new United Woodworking Company. For a while the two cash till companies worked independently although social connections seem to have been reasonable. In 1927 the Parish Council for example thanked both Harry Coombes and Alf Baylis for carrying out work to provide a coal store at the village hall.

By the second half of the 1920s, The Oxon Cash Register Co. was getting into financial difficulties. One factor may have been the building of a large show room (which later became Shipton’s cinema) described as a “white elephant” by Bob Coombes, and the old Baylis business was bought out using money from Sam Groves and William Willett. By 1929 Alf Baylis had moved to Lyneham and resigned from the Parish Council. He disappeared from view, although he is reported to have traded in furniture in Manchester and is believed to have died relatively young.

The Station Road works now became known as the North Works and was run by Harry Coombes while the Oxon Cash Register Co.’s works continued as the South Works under the supervision of Ted Coombes. Both units cooperated in the manufacturing process where required. For example the North Unit had a dovetailer machine while the South Works, which mainly made shop fittings, had a corner locker machine.

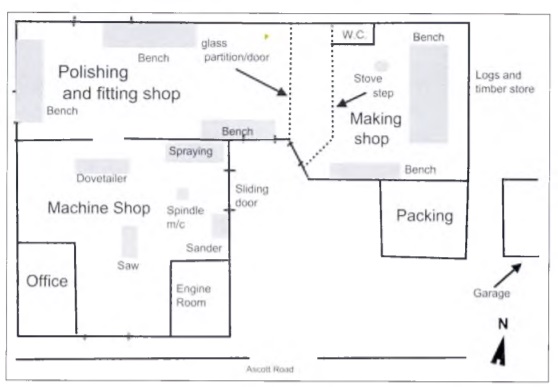

The layout of the Station Road or North Unit as it was just before the Second World War is shown in Diagram 2. The top shed with an engine in what later became the polishing shop was the extent of the first works. By the mid 1930s a second shed had been erected housing the machine and fitting shops. This second shed was joined to the first via the polishing shop. The adjacent business was Bradley’s Garage, belonging to Reg Bradley, who had served with Harry Coombes in the Royal Naval Air Service. Harry Coombes lived in Glenhurst opposite the Station Road Tillyard and then in 1935 moved to the adjacent villa, Hawthornes. In about 1945 a further shed was built parallel to the “lean to” and this housed the timber store, the fitting shop for the poultry incubators and the garage for Harry Coombes’ car. A small office and mess room were built to the right of the plan, ie parallel to the main road.

About one year after the move, in 1926, a young woman, Phyllis Siford (later Phyllis Longshaw and finally Phyllis Smith), came from grammar school in Cheltenham to be the new and indeed first bookkeeper. She later recounted (WLHS archives), that the administration was in a state of some disorganisation with bills stuck on nails and the cash flow not receiving the attention it required although this was probably to be expected in a new and growing business.

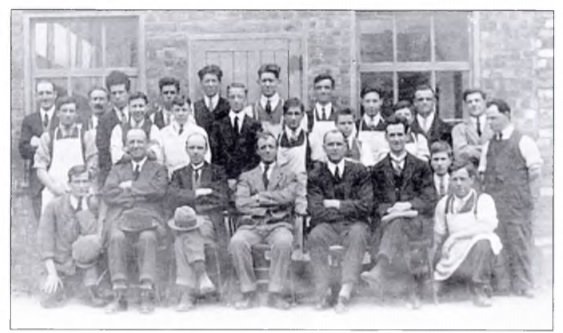

According to Bob Coombes, Ted did not get on with Phyllis but she and his father Harry always had a good mutual liking and respect even after she left in 1946 to set up the third Shipton operation, Wychwood Manufacturing Co. They were both very shrewd, the one a modern, well educated girl from outside the village while Harry had left school at twelve and was very much a pillar of the local community – Chairman of the Parish Council, a member of the Rural District Council, Church Warden, Grandmaster of the Oddfellows and on the Board of Governors of the Workhouse. Photograph 4 shows the workforce at the Station Road yard in about 1936.

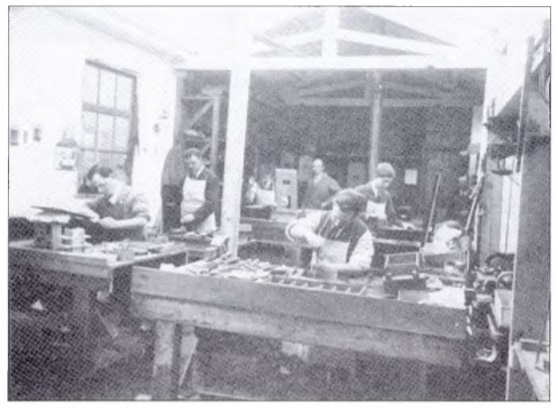

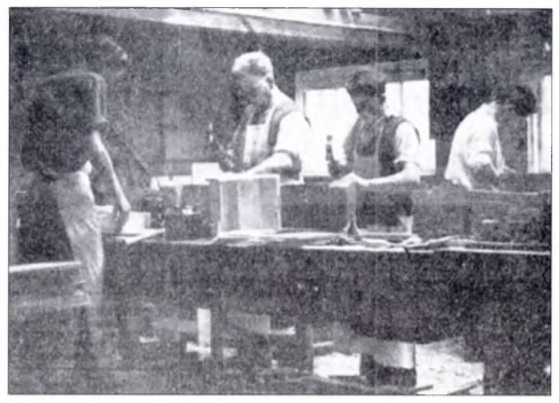

Photo 5 shows the interior of the Oxon Cash Register Co.’s workshop after it had been bought by the United Woodworking Co.

There is some disagreement over the identity of the workers shown on Photo 5. The best suggestion is that the man on the left is Jim Slatter. The two men (second and fourth from the left) are Jimmy Wallace and Harry Crabtree who had come to Shipton with Alf Baylis from Halifax. At the front right is Ernie Souch and behind him Albert Longshaw. The man between Jimmy Wallace and Harry Crabtree has not been identified.

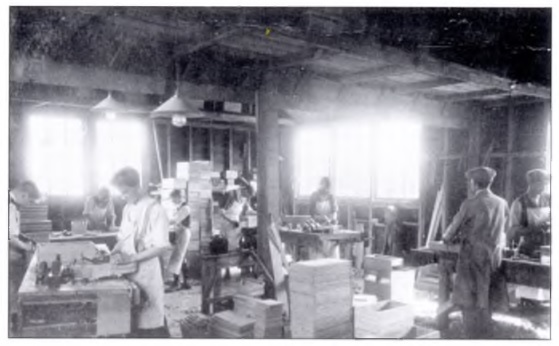

Photo 6 is of the interior of the Station Road Workshop of United Woodworking at about the same time.

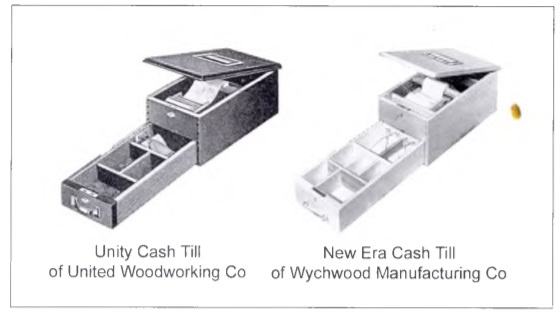

Both workshops were in operation until the start of the Second World War although by then the South Works was mainly making shop fittings. The Station Road Works concentrated on cash tills. The range comprised about a dozen models including one for fitting under counters (used in public houses) and one with a separately locked desk shaped top. Some wooden furniture was also produced (for example chairs for the Village Hall and cotton reel cabinets to a German design for Coates). There was still a relationship with Groves. This mainly took the form of Groves buying occasional fittings from United Woodworking and United buying English timber from Groves. Photo 7 shows typical Shipton cash tills.

One day early in the Second World War a Ministry of Supply controller, working for the Air Ministry, called at the South Works. He inquired whether they might be interested in making aircraft parts from wood. Ted Coombes apparently tugged his moustache in disbelief and showed the caller the door. Thus vanished any opportunity for Shipton to be the site for the production of the Mosquito fighter bomber! Shortly afterwards Ted sold off the machinery in the original works to Kings of Oxford and he, Reg Duester and about half a dozen other workers moved into the Station Road Works while about a dozen of the workforce including Fred Smith and Horace Pratley went to work at De Havillands (later Smiths Instruments) in Witney, ironically on the Mosquito.

Unity cash till – new era cash till of United Woodworking Co of Wychwood Manufacturing Co

Photo 8 shows the Great Western Railway lorry picking up a consignment of cash tills from outside the Station Road tillyard. The driver is Ernie Clemson and the photograph would have been taken during the mid 1920s. Bradley’s garage is on the right.

The old premises were used during the early war years to shelter cars owned by well off car owners from Birmingham. After the War, they became a store for agricultural materials for Pratt and Haynes. In the 1950s, films were projected in the old showroom. Its final use before demolition was by the Newbolds, of the Court stables, to house pigs.

Photo 6: United Woodworking Co.’s Station Road Workshop probably in the early 1930s and taken looking towards the end of the making shop The man front left IS Charlie Norgrove. The man facing away from the camera, second on the right is Jaybee Broom. On his left is Jim Slatter and on the extreme right is Sid Tierney.

During the Second World War the number of employees declined until, according to Bob Coombes, there were only two or three boys, too young for national service, and half a dozen women including his mother. Besides cash tills, they made battery boxes and rubber stamp mouldings for the Post Office.

By 1946 however the workforce had recovered to sixteen people. The list taken from the wages book for the week ending 19 April 1946 was as follows:

Machinist

H Pittaway

Makers or Assemblers

R Duester

S Tierney

P Hepden

J Sheehan

H Moss

G Duester

B Miles

V Brookes

H Pittaway

J Broom

F Smith

D Pittaway

Polishers

F Richards

R Brookes

Office

P Smith

This was the last page written in Phyllis Smith’s neat handwriting. The next week’s entries were in the hand of Mr R Williams (Ted Coombes’ son in law). A group of employees (Phyllis Smith with her husband Fred, Laurie Pittaway – who had been one of the originals to have split from Alf Baylis in 1923 with Harry and Ted Coombes – and Jaybee Broom) b^Jieved they could do better on their own and gradually left to found the Wychwood Manufacturing Company. Harry Coombes had apparently wanted to make Phyllis a director of the United Wood Working Co. but Ted had objected. Phyllis Smith left first. She was followed by her husband Fred Smith on 10 May (Alf Harvey rejoined United Woodworking that week as a polisher and Arthur Shirley also rejoined but as a maker). Laurie Pittaway left on 24 May and Jaybee Broom on 21 June.

At first they worked at Phyllis Smith’s bungalow, Alstone in Station Road just the other side of Bradley’s Garage but then took over workshops in the Ascott Road belonging to Alf Miles and used for his woodworking and undertaking business. Alf continued to work there until he died (and presumably was responsible for the “undertaking” mentioned on the new company’s promotional material).

Diagram 3 depicts the layout of the Ascott workshop as recalled by Bim Champness. The structure was of wood with a corrugated tin roof. There is no known photograph of the Ascott workshop and only one, rather poor photograph of the interior taken for the Oxford Mail (see Photo 9)

The workforce in the mid 1950s as recalled by Fred Russell and Bim Champness consisted of:

The four partners – Phyllis Smith who ran the operation, Fred Smith (in charge of making), Jaybee Broom (polishing) and Laurie Pittaway (machining). The partners all lived close to the workshop – the Smiths in Church Street, Jaybee Broom in Ascott Road and Laurie Pittaway in the High Street but next to Jaybee Broom’s house.

Bim Champness, who was Fred Smith’s nephew by marriage, was a polisher.

There were six assemblers – Bill Slatter (Ascott), Bernard Wicksey (Fifield), Philip Hackling (Milton), Basil Miles (Milton) and Sid Tierney (Shipton) plus a trainee assembler Fred Russell (Ascott).

There were evident tensions. Fred Smith suffered badly from asthma and was often unable to work so that Laurie Pittaway and Jaybee Broom felt they had to do more than their fair share. Jaybee Broom had taken something of a demotion in joining Wychwood Manufacturing. At United Woodworking he had been foreman in the making shop. Fred Smith in fact had started his career as Jaybee Broom’s “boy”. Laurie Pittaway (who later returned to work for United Woodworking in Station Road) was felt to have a rebellious streak and Fred Smith was critical of his cutting at times. It probably did not help that two’ of the four partners were married to each other and could carry on business conversations out of hours.

Conditions were hard especially in the winter. The wood glue used to freeze solid over night. At first heating was from the “slow but sure” stove in the making shop. It was Fred Russell’s job to pack the stove with sawdust the evening before and then get it started when work began again at 7.45 the following morning. There was apparently no water. He used to fill up a kettle from the neighbouring gas works so that Phyllis Smith could make tea for 9.45. She and Fred would then sit on the tool box and discuss priorities. Sometimes she would say, “There’s a bit of post Fred” and this was a signal for the directors to meet informally.

Phyllis Smith always had a reputation as a sharp business woman. She knew the value of information. In 1958, when the Oxford Mail visited both working tillyards, United Woodworking was frank about its current production level of some 200 tills a month. Wychwood Manufacturing’s output however was a secret! Phyllis Smith would allegedly tip the lorry driver, who collected the output from both tillyards, ten shillings a week so that he would pick up the tills from Wychwood Manufacturing after those of United Woodworking and she could see how well the competition was doing and to whom they were selling! She would also look at the United Woodworking Co.’s paying in book at the bank (these were apparently often left open on the desk at the bank in Shipton) and tie up payments with known deliveries. In this way she was able to undercut United Woodworking .

Wychwood Manufacturing concentrated on the production of cash tills (according to Fred Russell 80% of sales consisted of cash tills in batches of 30 units which would take up to three days to produce) although invoices prepared in the mid 1950s still listed ‘cabinet making, undertaking and general repairs’ among the activities. There was a greater concentration on exports than at the United Woodworking Co. and, according to Phyllis Smith, this brought support from the Board of Trade when Sam Groves tried to get them closed down just after the War.

In the 1950s employment at both tillyards fell by roughly half as wooden fittings gave way to plastic and more sophisticated cash tills became popular. Neither firm was in direct contact with its market as they only sold to wholesalers who generally marked up prices by 100%. Brunton and Williams of Peckham took around a quarter of the production of the United Woodworking Co. while Morden and Green, also in London, were an important outlet for the Wychwood Manufacturing Co.. Neither till producer had the means or perhaps the initiative to employ their own sales people and both suffered from a lack of space to allow them to hold stocks.

In 1972 the Ascott Road business was bought by a Mr Cohen of Adsit Typewriters of Birmingham who wanted to close it down and build on the site. Phyllis Smith stayed on for the new owners for a further two and half years until the business eventually closed in about 1975. After that the deteriorating building was briefly occupied by a tramp until a fire caused further serious damage. Now brambles have completely taken over the site.

The United Woodworking Company lasted three years longer. Harry Coombes had bought up the Groves, Willet and Clifford shareholdings and obliged Ted to retire just before his seventieth birthday in around 1954. Harry himself fell ill in 1956 and died in the following year. The day before he died, Phyllis Smith turned up to ask what arrangements were being made for the tillyard! She was told that this had been decided some three years earlier. Harry’s son, Robert (Bob), who had his own busy accountancy practice, took over the running of the company (he had been partially involved during the period of Harry’s illness). At Harry’s death about 80% of revenue still came from the production of cash tills. Bob made efforts to diversify the business. New ventures included pheasant and turkey incubators, bale sledges, bar and drapery store fittings (Avery’s store in Shipton was refitted twice and Langston’s pub in Kingham was fitted out as a night club) and garden furniture.

Roger Watts worked at United 1959-1964. He estimates the business employed approximately 17 people at that time. Harold Lord was the foreman. Other workers he remembers included Jim Claridge machinist, Terry Stowe fitter, David Rathbone, assembler and Roy Rathbone assembler. Interestingly there were also three mixed race assemblers, Mervyn Case, Johnny Neibeer and Clifford Glynn whose fathers had been American servicemen during the Second World War. Working hours were to 12.00 with a quarter of an hour for tea at 9.45. Lunch was from. to 13.00 and then work resumed until 17.30 with a ten minute tea break at 15.00. There was work on Saturdays from 7.30 to 12.00.

As with the first tillyard, clocks were an important feature in the daily life of the business. Roger Watts relates how Jim Claridge, while playing football, hit the works clock and broke the glass of its elaborate cupboard. Harold Lord continued to open the glass case for six weeks to wind the clock up before he realised the glass was missing!

From the time of the business’s inception until 1978, according to Bob Coombes,- it rarely sold less than 300 cash tills in any one month. The peak month was 3,000 tills probably in the boom years just after the Second World War! Decimalisation in 1972 however led to the introduction of even more sophisticated automatic cash tills and there was no longer the need to write on a paper roll as with the Shipton tills. The National Cash Register Company (which had first inspired Gledhills and indirectly Alf Baylis fifty years earlier!) had large stocks of automated decimal machines which would do both the calculation of the sale and the recording. Demand for traditional wooden cash tills dried up. Even the Company’s diversification programme ran into problems. Larger, specialist agricultural machinery manufacturers brought out bale sledges which stacked the bales so that they were easier to pick up. Several large orders for turkey incubators were cancelled when hire purchase of agricultural machinery was stopped. By 1978 the business was no longer viable and was wound up. Of the long-time workers, Philip Hepden, Eric Pratley, Horace Pittaway, Ernie Hedges, Jimmy Woodward, Alf Harvey and Reg Duester were there until the end.

Shipton probably produced at least 500,000 wooden cash tills in the half century from 1920. There are no production records so this must remain a rough estimate. What is true is that this micro industry allowed a significant number of men in the Wychwood villages to exploit carpentry skills largely learned at Alfred Groves and Son so that they could earn higher rates of pay than were available elsewhere (including Groves) and generally enjoy better job security without having to commute to Oxford. Its insularity was initially a strength but led eventually to its demise because the industry was, to use the modern jargon, product orientated rather than market orientated.

This article owes much to the painstaking collection of information, including audio recordings made over the years with Wychwood inhabitants, by John Rawlins. The author is also very grateful for interviews with Bob Coombes, the son of the founder of United Woodworking and Roger Watts who worked there from 1959 to 1964.Gordon Duester who worked at United Woodworking at the end of the War also made several valuable suggestions. Similarly, with regard to the Wychwood Manufacturing Co, information and recollections were generously shared by Fred Russell who worked at the Ascott Road works from 19s4 to 1958 and then again from 1964 to 1966 and Bim Champness who also worked at the Wychwood Manufacturing Co. from 1956 to 1966.