The following article appeared in the Wychwoods Local History Society Journal Number 4, published 1988. It features an in-depth study of the development of the building and its fabric.

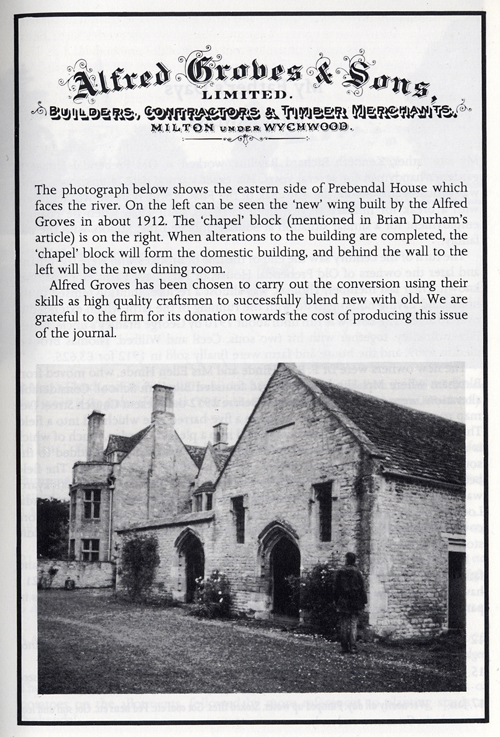

This image of the Prebendal was published with the article, with accompanying reminder of the work carried out on the building in 1912.

The text of the article is also available here as a PDF

Prebendal House, Shipton under Wychwood

BRIAN DURHAM

Senior Field Officer, Oxford Archaeological Unit

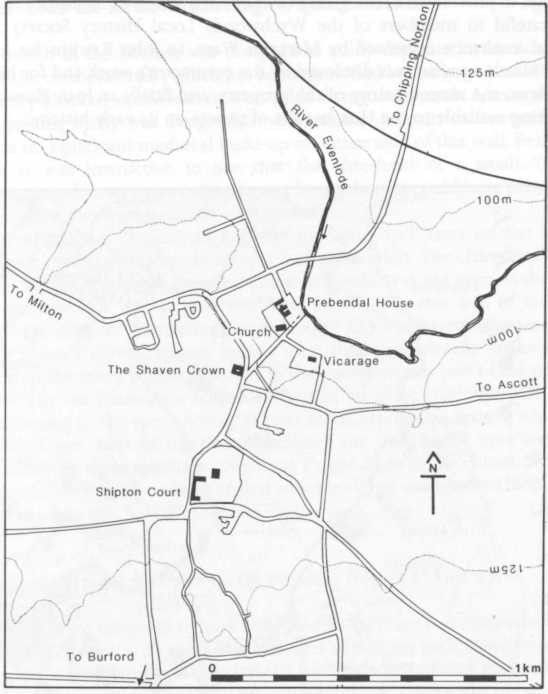

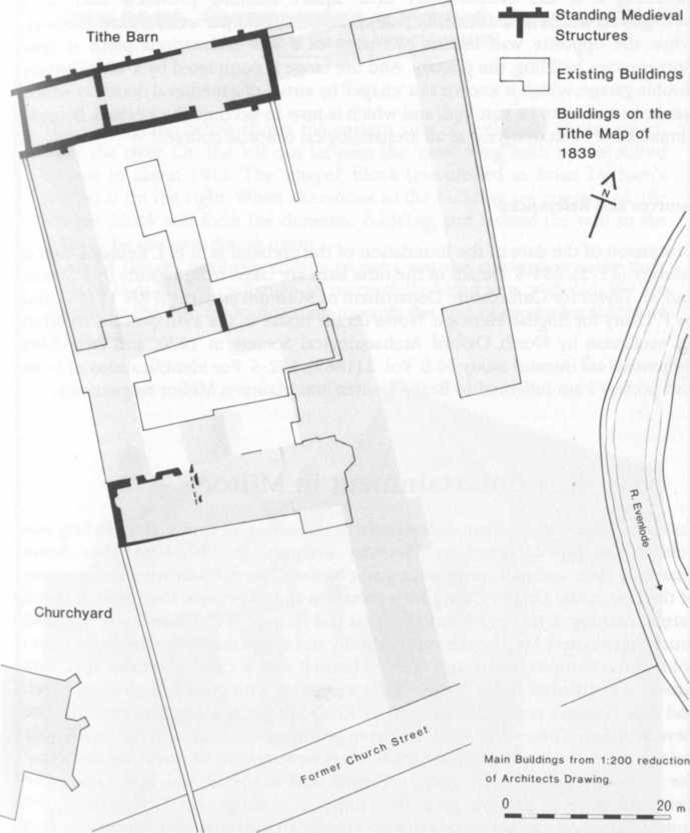

Prebendal House and its ancilliary buildings stand in an acre of garden on the east side of the village of Shipton under Wychwood. The plot is roughly rectangular, lying between the churchyard of St Mary’s Church and the flood plain of the river Evenlode. The property was formerly approached from the direction of the modern village green via Church Street, but a new entry from the north-west was established in the mid-19th century and has now become the main approach to the replacement front door in the 20th century east extension.

Following a succession of private owners, the house and grounds have been acquired by Dr and Mrs N. Clarke on behalf of Mitrecroft Ltd for conversion to a complex of sheltered accommodation including residential and nursing care facilities. The necessary alterations are designed to make minimum visual impact on the impression of a Cotswold manor house. There will however, inevitably be major internal works to provide seven suites of bedroom, bathroom, sitting room and kitchen, 24 bedsitting rooms with bathrooms en suite, and various communal rooms. The tithe barn is to be restored and refurbished to provide an indoor swimming pool and concert hall/theatre.

The house itself exhibits several architectural features which indicate medieval origins. The bam has been compared with major Oxfordshire 15th-century barns such as Adderbury, Swalecliffe and Upper Heyford, and there are medieval features in the range of small buildings dividing the two. The complex as a whole is roughly what would be expected of a rectory in any rural parish, with a domestic area and a separate barn area for the storage of tithed produce. Assuming that it is included in the Domesday valuation of £72 for the Royal Manor of Sciptone in 1086, it may indeed have begun life as a rectory, either on this site or nearby.

The first surviving reference which can be seen to relate to this property or its predecessor is between 1111 and 1116, in a writ which implies that Shipton church had been granted to Salisbury Cathedral since the accession of Henry I (ie after 1100). It had been given by Amulf (or Arnold) the Falconer ‘for his son Humphrey’. Amulf was probably a royal officer, and may have been the king’s representative on the royal estate of Shipton. By extension therefore, his son Humphrey may have been the rector, who would have been a wealthy man on the valuation of 45 marks (£30), one of the twenty richest manors of any sort in Oxfordshire on Domesday valuations. Perhaps Humphrey wanted to join the chapter of Salisbury cathedral as a canon, and to pave the way for this his father asked the King to grant the revenue from his rectory to the cathedral in perpetuity. The church, the rectory and the glebe lands would thereby have become a ‘prebend’ of the cathedral, and the canon the first ‘prebendary’ of Shipton. The details are mere supposition, but the story is typical of the way in which cathedrals and monasteries were increasing their revenues in the post-Conquest period by acquiring interests in outlying manors.

The general plan of Prebendal House may therefore date back to a formative period in English history. The new owners were pleased to take advantage of the proposed alterations to learn more about the house, and thereby to provide their future residents with a historical perspective in their new surroundings. The Oxford Archaeological Unit was in turn pleased to conduct a series of small excavations aimed at sampling the deposits beneath the various ranges of buildings, to provide archaeological evidence for a review of its history. The Unit is very grateful to members of the Wychwoods Local History Society for their practical assistance organised by Margaret Ware, to John Rawlins for keeping a regular watch on what was disclosed by the contractor’s work and for his tireless research on the recent history of the property, and finally to Joan Howard-Drake for making available to the Unit her file of papers on its early history.

A small trench in the kitchen was designed to study deposits in the north-west corner of the medieval ‘hall’, which has been identified by the large late 13th/early 14th century blocked window in its west gable facing the church. A second trench in the adjoining lobby was designed to seek similar deposits in the north wing. There was no significant medieval build-up on either side of this wall, Feature (F) 306, but it was instructive to see that the threshold of a small ‘Gothick’ communicating doorway was originally at a level where it could have provided an opening from a medieval hall into a courtyard.

The interpretation of this range as the medieval ‘hall’ rests on the blocked window and the massiveness of the west and north walls. The chamfered course shared by the foundation of the west and south walls was not seen to the north, perhaps because this was a more mundane facade. The east wall of this block (F306/1) was seen in contractor’s excavations for a new partition wall, and alongside it were several human burials on a similar alignment to the church. These add to the many burials reported in the past from this part of the property, and show that the house was built over part of an older churchyard. A second partition footing to the west showed deeper fill of a ditch-like feature which may have divided two parts of the old churchyard; the only burial here was much deeper, and lying along the ditch roughly at a right angle to the church. The ditch may have still been visible when the first stone building was planned, because the footing was taken much deeper here (F306).

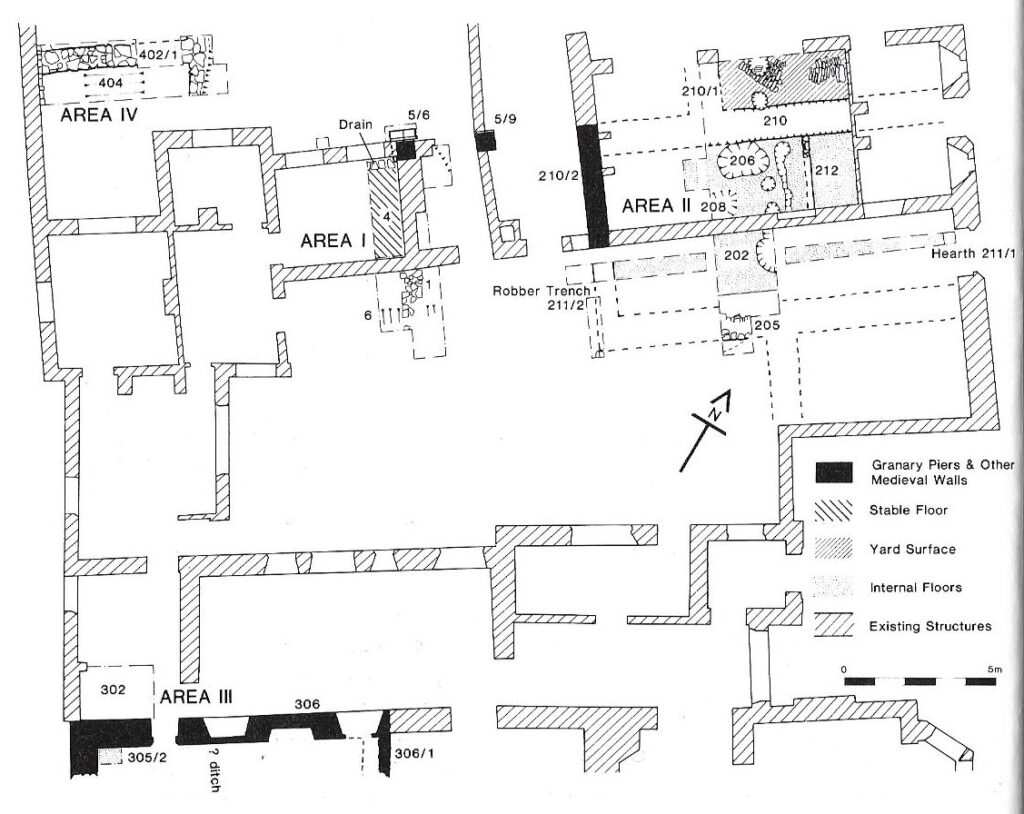

The Excavation: the ‘chapel’ and garage building (Figure 1, Area II)

The trenches were designed to look at deposits which are to be disturbed by the proposed dining rooms. By extending trenches within the garage and courtyard it was possible to reveal much of the plan of a late medieval building slightly broader than the existing one (built in 1900) but offset by about 3 metres to the south. The stonework of the foundations had been largely robbed out (F20S, 210, 211/2) but the standing west gable of the garage could easily be a medieval survival (F210/2). Within the medieval building was a thick accumulation of ashy floor yielding minute fragments of Tudor-type pottery, fragments of eggshell and a charred grain of barley (Layers (L) 201, 202 etc). This suggests domestic occupation, although there were three large hollows dug into the floor which might argue that there had been an industrial usage which for some reason had left no material traces (F203, 206, 208). A partition was later added, possibly a screened through-passage (F212).

Most of the medieval finds came from this area. Bruce Levitan (environmental archaeologist, Oxford University Museum) reports that there were many bone fragments, mainly sheep and cattle, but including rabbit, goose, domestic fowl, wild duck and bony fish. Maureen Mellor (pottery researcher, Archaeological Unit) was interested to find that the medieval sherds were thicker, coarser and greyer than previous groups from Shipton, and there was nothing which closely resembled “Wychwood Ware”.

She suggests two possible reasons – either the sherds belong to a period which we have not seen from Shipton before, or they have come from vessels with a specialised function in the barnyard area. The absence of Wychwood ware may mean that the Prebendal household could afford better, either fine vessels from Brill in Buckinghamshire (3 sherds) or even metal vessels. Maureen hopes that her Survey of Oxfordshire Pottery will answer some of these questions.

Most interesting in this area was a substantial north-south wall sealed beneath the building F214 (not on plan), immediately west of F212. It appears to have had metalled surfacing to the west but nothing to the east, and is therefore tentatively suggested as an early curtain wall to the prebendal house at a time when perhaps the flood-free land may have been no more than a narrow strip against the churchyard.

If this was indeed the line of an early boundary wall it was clearly pushed eastwards in medieval times by the tithe bam (cruck trusses circa mid-14th century) and by the excavated building (not earlier than late 13th century on pottery evidence). New buildings of this period would explain the existence of two perpendicular doorways and windows which have been reset in the east facade of the 1900 building. These are reputed to have come from the ‘chapel’, but there is no clear indication where this was. Certainly the later use of the excavated building was domestic and it seems to have been described as a ‘barn’ by the Oxford Architectural and Historical Society in 1870. The description seems to imply that the medieval doorways and windows were originally in the south elevation of this building, ie in the wall F20S, and it was perhaps this which gave rise to the term ‘chapel’.

The Excavations: the ‘Romanesque building’ and farmyard (Figures 1 and 2, Areas I and IV).

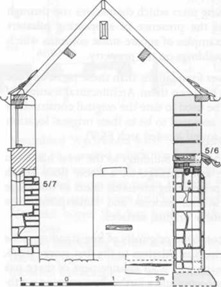

Figure 2: The ‘Romanesque’ building; left, internal elevation of west gable; right, external elevation of north wall; top, reconstruction of early 13th-century granary

The most interesting surviving structure in the present north range is a small building with several Romanesque features recognised by John Blair of the Queen’s College, Oxford. The features include two shallow pilasters rising to first floor height (F5/6, S/9), a distorted round-headed doorway (F5/7), and a fragment of an impost which presently supports a timber lintel. Excavation has established that:

1. The pilasters are attached to free-standing piers which themselves rise through two storeys. Their overall height and the presence of supporting pilasters distinguish them from several other examples of square stone columns which support open-fronted farmyard-type buildings on the property.

2. The walls of the building have shallower foundations than these piers, and are therefore in the nature of infill panels between them. Architectural features of the walls therefore cannot necessarily be used to date the original construction of the pier building, even if they were assumed to be in their original location (which is questionable for at least the round-headed arch F5/7).

3. The floor levels within the adjoining range of buildings to the west had been dug at some time to give headroom and drainage for a stable floor which existed by the 18th century (L4). Any pre-existing medieval floors of this range are likely to have been removed in this process and consequently the excavation could not be expected to show original surfaces.

The ‘Romanesque building’ therefore consisted originally of free-standing stone piers 60cm (2ft) square, buttressed by 7cm (3in) pilasters to the first storey (F5/6, S/9). Incorporated in the upper part of each pier is an arrangement of three oak timbers running right through the pier east-west, and a further two running north- south, let into both the east and west faces. These immediately suggest composite supports for a first floor, and their location means they must have been inserted when the upper piers were built. A building raised on such high piers could well have been a granary, but as such it would be very unusual in an area where the familiar type of granary is raised no more than 60-90cm on ‘staddle stones’. This exaggerated height, coupled with the interesting, slightly stylised buttressing provided by the pilasters, could mean that the piers are very rare survivors of a 12th to early 13th-century granary. They survive principally because the infill panel (F5/8) formed a wall which was on a convenient alignment to be reused in successive farmyard buildings.

The granary is assumed to have been two bays wide at least, and subsequent infilling between the piers would have created a useful space. Eventually however it must have been replaced by buildings used for stabling animals, like that now surviving. This may have happened in medieval times, because a drip-course at a high level in the west gable of the adjoining garage building (F210/2) suggests that this was an external wall face, rather than something built against the end of a pre¬existing granary.

The Area IV trench was dug against the churchyard wall with the assistance of the Wychwoods Local History Society. It exposed the foundations (F402) and sloping floor makeup of an agricultural building shown on the 19th-century maps, probably of no antiquity. Most interesting was a ditch (F404), parallel to the churchyard wall, and yielding early medieval pottery. Was this an early division of the churchyard continuing that beneath the hall range? It seems possible.

The Shape of the Medieval Manor House

From the archaeological and topographical evidence it is possible to produce a plan of Prebendal House for the post-medieval period, and to extrapolate back to the medieval without stretching the evidence too far. The house would have occupied the strip of land between churchyard and floodplain, as previously recognised by Paul Drury (Inspector of Ancient Monuments, English Heritage). Early Saxon grass-tempered pottery in secondary deposits implies that there had been early settlement nearby, perhaps associated with a river crossing, but there was nothing to suggest any continuity of settlement through the Saxon period. If there was a rectory at Shipton before about 1100-16, it need not have been on this site, and human burials under the house and elsewhere suggest that part of the property was cut out of the Saxon churchyard. Perhaps therefore in the 12th or 13th centuries the churchyard was reorganised, making space for a house fronting onto Church Street, with a ditch demarcating the boundary between the two.

This gives a historical framework, and means that what is known of the house can be usefully compared with, for instance, the Bishop of Salisbury’s 12th-century houses at Old Sarum and Sherborne Castle. The former is sure to have been known to the incumbent when the property became a prebend of Salisbury in circa 1127. Both this and Sherbourne were built round very compact courtyards of between 30-40 metres outside dimensions.

The two ranges surviving at Shipton in 1839 (tithe map) could reflect a tradition of a quadrangle of buildings around the south lawn. Its proximity to Church Street may be significant. The street leads off the area of the modem village green and is now a cul-de-sac, but has many of the characteristics of a main road through the village leading to a river crossing and up the hill towards Chipping Norton. This would give additional significance to the frontage. No doubt there would need to be an access to the rear part of the property, where there may already have been a barnyard.

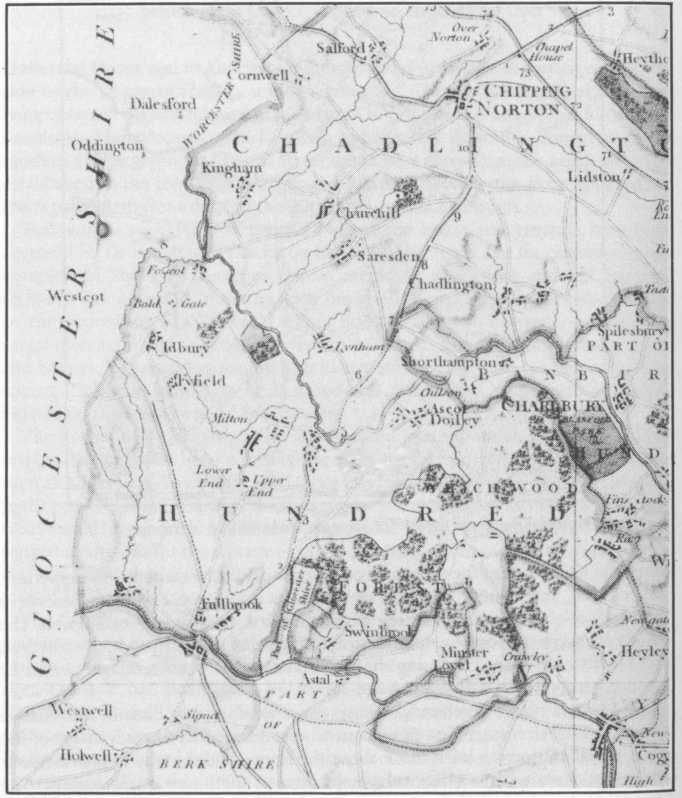

The Salisbury houses quoted above are both ‘castles’, and it is important to note that in a 12th-century setting many manor houses of the size of the Shipton prebend would have been fortified against the anarchy of Stephen’s reign (1135- 54). One need look no more than two miles downstream from Shipton to find two sites on the same bank of the Evenlode which were provided with impressive earthworks (Ascott Earl and Ascott D’Oilly).

The lack of earthworks may indicate that the Shipton prebend was comfortably protected by a fortress elsewhere in the village, perhaps the royal manor, wherever that may have been. It might be argued of course that such defensive works were restricted to secular magnates who were involved in the political hurly-burly of the period, but the sheer wealth of the prebend would make it a subject for protection.

On the other hand the lack of defences may simply mean that the rectory was elsewhere in the 12th century, and it is interesting to note that the 1870 visit by the Oxford Architectural and Historical Society concluded that it was the vicarage, ISO metres to the south, which had the defences. Could it be that when Elias Ridell presented the first recorded vicar in 1227, the vicar took over the existing prebendal house, and a new house was built on part of the churchyard? This would fit the assumed dating of the earliest tangible remains, the granary piers.

Tithing of an estate the size of Shipton must have produced large quantities of grain, all requiring storage in dry vermin-free conditions. The granary would have been at least three bays long and probably two bays wide along one side of the barnyard. Since the structures are unprecedented, it is a little difficult to be categorical about their date.

The stone is heavily weathered so that the tooling has almost disappeared, but it is apparently not as consistently diagonal as would be expected of 12th-century ashlar. I am therefore indebted to John Blair’s opinion that such slender pilasters have no place in Gothic architecture.

Even when applied to a free-standing pier as in this case, we agree that they must be Romanesque and hence no later than the early 13th century. In time the ground area beneath the granary could have been used for storing other materials and equipment, leading to the construction of walls between the piers, for weather¬proofing and security. This point may have been reached by the mid-14th century, perhaps the time of a major building programme which saw the construction of the great barn in its original timber form.

The shape of the barnyard would by this time have been well established. The layout was to be completed by a late medieval building continuing the line of the granary eastwards. The contrast between the thick carpet of ash in this building and the cleanliness of the floors of the hall range may indicate a difference in function, but the ash does not necessarily mean an industrial usage. Similar floors occur commonly in medieval domestic buildings in Oxford, and it is not impossible that this was in fact the residence of an official concerned with the administration of the prebendal barnyard.

Conclusion

It is ambitious to attempt to tell the history of such a complex building by digging a few holes in one area but this is the way that research on medieval buildings is likely to go in the future, and the exercise must be seen as a challenge.

There can be no doubt that the property has been taken out of the churchyard, possibly in the early 12th century but more likely around 1227. The only building of the period is the putative granary, but the existing hall or chamber block could have been built within a century of the later date, and both the barn in its timber form and the Area II building not long after.

The new discoveries also focus interest on the vicarage site, as a possible predecessor of the prebendal house. The most memorable thing to the writer however is the present north range of buildings.

The western room has been converted from a cowshed or stable, while adjoining it is the extraordinary little square building presently used as a passageway, with a re-set or deliberately faked Romanesque arch for one doorway, while the opposite wall retains two piers of a less ostentatious piece of true Romanesque building, the granary. And the range is completed by a 20th-century double garage, which is known as a ‘chapel’ by virtue of a medieval doorway which has been built into its east end, and which is now to become the kitchen. It could almost have been designed as an archaeological obstacle course.

Sources and References

Discussion of the date of the foundation of the prebend is in E. J. Kenley’s Roger of Salisbury (1972), 234-5.

Details of the tithe barn are taken from reports by J. Steane and M. Taylor for Oxfordshire Department of Museum Services (PRN 11755), and by P. Drury for English Heritage.

Notes on the house in the 19th century are from an excursion by North Oxford Archaeological Society in 1870, and Froc. Oxford Architectural and Historical Society N. S. Vol. 2 (1869), 132-5.

For identifications of bone and pottery I am indebted to Bruce Levitan and Maureen Mellor respectively.