Here is an extended piece by John Rawlins, taken from the WLHS Journal No 15 (2000). We republish it here as part of an occasional series celebrating the work of the Society over time. (A PDF of the Society’s Journal No 15 can be found here).

Those who study the nineteenth-century census returns from 1841 onwards find that the names of persons living in households can usually be read, but, to find where those households were within the village is more difficult. The local enumerator for each census did not necessarily follow the same route as his predecessor and give only the vaguest indication of where people lived.

In 1841 Milton’s enumerator divided the parish into Upper and Lower Milton and names only three definite locations, most of them roads, in each area to cover the 118 buildings. By 1891 the census enumerator gave little more detail or specific names to the households he visited and in Shipton James Alfred Willis named 29 buildings or groups of buildings he called on, but he named no thoroughfares.

Mr Gilbert the Milton enumerator for 1891 named 17 individual buildings and four roads when he completed his census of the 215 households. Some of those named survive today, such as High Lodge, Springhill Farm and Sunrise; others are different through change of use, for example Coffee Tavern to the present Wychwood Surgery; or the same name has moved to another house. Heath House in Church Road, Milton kept that name until 1930 when the then owner Brigadier General Kirby changed it to Heathfield House. His reason for the change of name would seem to be to allow him to take the name Heath House with him when he married Mrs Paisley in March 1930. So, on her marriage Mrs Paisley not only took on the new surname of Mrs Kirby but her own home, Kohima, now took on her new husband’s choice of name, Heath House.

|

Kohima was the name given to the property in Lyneham Road, Milton by Mrs Damont whose husband had been killed at Kohima in north-east India in 1857 during the Indian Mutiny. Apart from the house there were stables and coach house complete with clock tower, a pair of semi-detached cottages and six bungalows with their exteriors built from corrugated iron and using the name Kohima. Today the name only remains on the bungalow built on the site of two of the former corrugated iron bungalows.

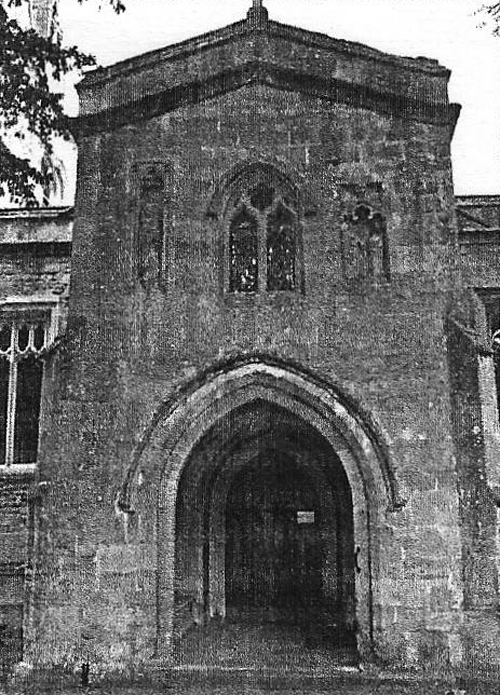

Soon after the building of Matthews mill in 1911, a pair of semi-detached cottages were built in Station Road, Shipton, to house employees at the mill. One of the first occupants was the clerk, Mr Goss and his wife, from the Reading area. He named the cottage Falklands after the island of that name where he was born and to which his great grandfather had emigrated in 1850. In the I920s the Goss family moved to another Matthews tied cottage, Pike House, Station Road. This was named after its former use as the gatekeeper’s house on the old turnpike (see photo page 63). As he approached his retirement Mr Goss had a bungalow built for himself in Bruern Road, Milton. He did not live long enough to live in it but is still carries the name he gave it – Falklands.

Like Falklands and Kohima, other house names have been brought to the area. The first Matthews home in Shipton was called Tothill from the family farm in Lincolnshire. This name was then changed to Holmwood, and changed again to Cromwell House and now back again to the present Holmwood. When called Holmwood before the Second World War, part of the grounds were used by Shipton Bowls Club, and during its spell as Cromwell House after the war it was home to the Wychwoods Tennis Club. In 1977 much of the grounds of the house were developed as a residential estate, taking the name of the original house, Tothill.

At the time of his marriage Samuel E. Groves of Alfred Groves and Sons built a pair of semi-detached cottages opposite the present Wychwood Church of England School. Mr Sam and his wife, Muriel, called their new home Berwyn to remind them of their honeymoon spent in North Wales.

A larger house was subsequently built for them on adjacent land and called Four Winds, after John Buchan’s book The House of the Four Winds.

About five years ago two members of the Basson family, whose relatives had been licensees at the Quart Pot at the turn of the century, called on me asking where The Anchorage was. They had been told that it was in Frog Lane, Milton, but having checked all property names they could find not find it. Luckily I could recall helping my father prune the roses for Mr Southam at The Anchorage some fifty years ago. Since then it has changed its name to Orchard House.

The Anchorage was built towards the end of the nineteenth century when two other neighbouring buildings in Frog Lane were built in non-vernacular style – Holmwood and Frogmore House. The former has been renamed Woodside and the latter became Forest Lodge in the I930s which it remained until the I950s when it became Forest Gate. The previous name of Forest Lodge was transferred to a newly-built house on the opposite side of Frog Lane, and the original name, Frogmore House, was adopted by another new house, as Frogmore, in Frog Lane.

The name St Michael’s was used in Shipton for the two houses below the Crown (now called Ivan House and Gales Green) when they were run as a boarding school/college for young ladies from 1869. The name transferred to a newly-built school/college in Milton Lane in 1881, and the name remained when the building was subsequently occupied by the Waifs and Strays Society and during its requisition by the military during the Second World War. The building then became a corn mill and chandlery for Alfred Meecham and Son and the name again transferred. This time it was to the site opposite on which council houses were built in the late 1940s – St Michael’s Close. The building built as St Michael’s in Milton Lane was demolished in 1989 and the site redeveloped as Willis Court.

One might have presumed that Jubilee Lane in Milton had some connection with the celebrations concerning Queen Victoria, but the name is derived from the 50th Jubilee anniversary in 1889 of the building of the Baptist chapel at the top of the High Street. At that jubilee it was decided to raise subscriptions for the building of a manse in the lane which had been variously known as Dix’s Lane. The Road, Groves’ Lane and Barnes’ Corner and is now known as Jubilee Lane

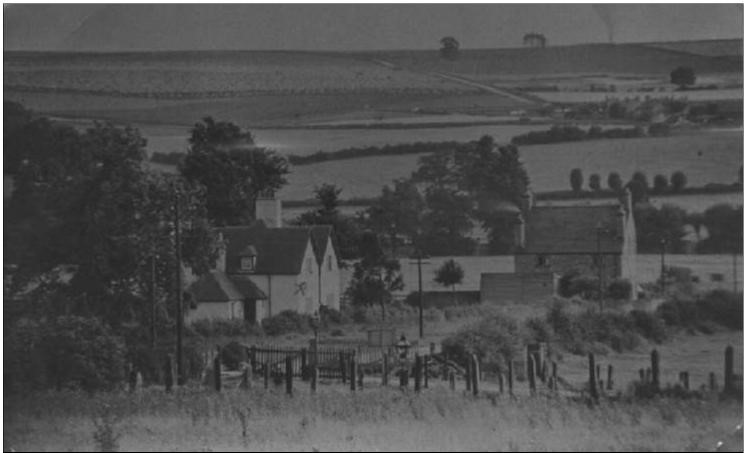

Ariel view of Shipton in Winter in the 1920s. The aeroplane wing can be seen in the bottom left corner. The white pathces in the fields in the centre are hoar frosts

From my limited research of records of Milton and Shipton it would appear that in the late nineteenth century very few residential buildings had names. Exceptions were farms and the larger properties – Shipton Court, Shipton Lodge etc, and the inns. Public buildings like schools, churches and chapels also had names. Small cottages had no names unless they were in a row or group when a collective name was used, as with Magpie Alley, Mount Pleasant and Fiddlers Hill in Shipton and The Square, Frog Lane and Hawkes’ Yard in Milton.

In the twentieth century the spread of the naming of buildings was slow, although new buildings were usually given names and there was some up-market naming of the already existing names.

In the early 1920s there was some attempt with numbering properties on the newly-built estates, a policy which continues today. But the numbering of the older roads has progressed little, with the exception of Milton High Street.

For some reason, unknown to me, it was around the late 1930s that more of the smaller properties were given names and by the same time the names of most roads and lanes had evolved into the names generally accepted today.

Today all buildings have a name or number (some both) as well as a road or street name, and both house and street names are displayed on boards or plates and are recorded on maps. Unfortunately for the local historian some house names have been changed in the last one hundred years, a few more than once, and any owner can change the name of their property at any time.

A PDF of this article can be downloaded here