The following article by Anthea Jones was published in the 1995 Wychwoods Local History Society Journal No10. It asks some interesting questions about the origins of the Shipton prebend, and charts the political background to the development of the Prebendal in Shipton. The article is also available as a PDF here.

The Seventeenth Century Puzzles over Shipton Prebend

Anthea Jones

The fortunes of Shipton prebend during the seventeenth century provide an insight into national political events. A prebend is a ‘provision’ of income for a cathedral canon. In Shipton’s case, the provision had been made for a canon of Salisbury Cathedral who owned the land and drew the tithe income which had once been allocated to the Rector or Parson. A canon of Salisbury was thus Rector of Shipton, and the Rectory or Parsonage House can also properly be called the Prebendal House.

There are several historical puzzles about the Shipton prebend. One puzzle concerns the statement that the prebend was ‘annexed’ to the Regius Professorship of Civil Law at Oxford by Act of Parliament in 1617. No parliament was called between 1614 and 1621 and so there could be no act of parliament in 1617. James I found parliament an exceptionally difficult institution, and as far as possible he avoided summoning it. He commented that:

‘I am surprised that my ancestors should ever have permitted such an institution to come into existence. I am a stranger and found it here when I arrived, so that I am obliged to put up with what I cannot get rid of.’ (1)

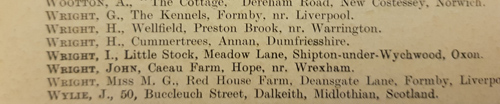

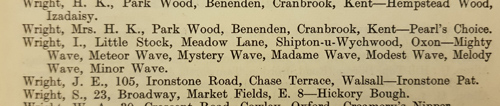

The statement about an act of 1617 being concerned with Shipton prebend is made in a number of books including the Victoria County History of Wiltshire volume III (published 1956), which in turn had drawn the information from the register of office holders of Salisbury Cathedral published by W.H. Jones in 1879. In fact, James I had given the Shipton prebend to the Oxford Professor of Civil Law by his own authority. He issued a Letter Patent or ‘open’ letter on 20 March in the fifteenth year of his reign. The document is in the archives of the University of Oxford held in the Bodleian Library. It is endorsed by the archivist ‘1618’. As James succeeded to the English throne on 24 March, his fifteenth year ran from 24 March 1617 to 23 March 1618, so the grant was made in 1618. (2) The canon of Salisbury who held the Shipton prebend, George Proctor, had died in 1617, which had given James I his opportunity, and hence no doubt Jones’ assumption about the date of the grant.

The Letter Patent recites in Latin how interested James I was in encouraging learning in his University of Oxford, and in particular his special favour towards the Professor of Civil Law, whose stipend he had supplemented with the Shipton prebend. He therefore granted the prebend to the Chancellor, Masters and Scholars of the University, and they were to appoint the Regius Professor to it whenever it should become vacant; the Letter Patent said specifically that the man need not be in holy orders, despite the fact that he was to be rector of Shipton and a canon of Salisbury.

As the King appointed the Regius Professor in the first place, it was a mere formality for the Chancellor, Masters and Scholars to appoint to the prebend, but it was this aspect of the arrangement which was apparently later regularised by an Act of Parliament, because the King had effectively given away his traditional right of appointment. The Regius Professor accordingly enjoyed the revenues of the Rectory of Shipton for the next 237 years, until 1855, when the recently created Ecclesiastical Commission investigated and reorganised Salisbury’s income and the prebend reverted to the church.

The connection of Shipton with Salisbury Cathedral was not broken in 1618, it was merely the nature of the appointment which was changed. As the Bishop of Salisbury wrote later in the century, the Regius Professor was still “presented to the Bishop, obliged to take the oath of canonical obedience to the Bishop, to preach in the Cathedral church, to pay stall wages etc. and to perform all other things, as other Prebendaries are obliged. (3) (Stall wages were paid to vicars choral of the cathedral).

The Professor of Civil Law appointed Shipton’s vicar and was responsible (as rectors always were) for the upkeep of the chancels of Shipton and Ascott churches, and he paid the stipend of ‘such as serve the cure in the church of Ascot’. (4)

The vicar of Shipton was also paid a stipend but in addition had a small estate of land and some of the parish’s tithes for his maintenance. It appears from a lease of 1641 that the rector or prebendary was also responsible for the upkeep of part of the bridge leading to Chipping Norton. (5)

The Regius Professor of Civil Law in 1618 was John Budden and he therefore became rector of Shipton and canon of Salisbury. In 1620 Richard Zouch succeeded him, and he was still in office when the estate was confiscated by Parliament. During the Civil War between Parliament and Charles I, the Church of England was transformed into a presbyterian church, and archbishops and bishops, and deans and chapters of cathedrals were abolished.

The victorious Parliament set about selling the episcopal estates in 1650, to which end they were first carefully surveyed. In Shipton, the five parliamentary commissioners found 40 acres of arable land in the common fields, 25 acres of wood, that is half Stockley coppice, and 14 acres of pasture and meadow, together with the Parsonage house, barns and outhouses valued at £35. The tithes of grain, hay and wool in the parish, ‘which parish doth comprehend the several villages or tithings of Shipton, Milton, Lyneham, Leafield, Ramsden, Langley and part of Ascot’ were worth £303. Dr Fox, doctor of physic of Fetter Lane, London, leased the estate from Dr Zouch for £50 per annum. The vicar’s income was estimated at £40.00 (6)

After the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 the Bishop. Dean and Chapter of Salisbury recovered their Shipton estate. In 1661 a new lease was made by the Regius Professor, now Dr Giles Sweit, with James Stocke of Waltham Abbey, yeoman. (7) All the routine expenses, including forty shillings ‘stall wages’, were to be met by the lessee. There was an interesting obligation of hospitality which was also passed on from the prebendary to the lessee. Every Sunday and festival day. James Stocke

‘…. shall invite and entertain and have to his Table att Dinner and supper two couple of honest and neediest persons being dwellers in the said parish, allowing them sufficient Meat and Drink for their Relief to the Intent good hospitality may be kept and maintained within the said Mansion place.’

Was this medieval tradition actually observed?

References

1 S.R. Gardiner, History o f England 1603-1642 ii, 251.

2 Bodleian Library/WPg/10/1.

3 Bodleian Library/Tanner MS 143 f. 103.

4 Oxfordshire Archives/Misc. Winch.1/1.

5 Oxfordshire Archives/Misc. Su. XLII/1.

6 Oxfordshire Archives/Gen.XXV/ii/1.

7 Oxfordshire Archives/Misc.Winch.I/1.