Here is an extended piece by Norman Frost, taken from the WLHS Journal No 2 (1986). We republish it here as part of an occasional series celebrating the work of the Society over time. (A PDF of the Society’s Journal No 2 can be found here).

The following are extracts from the letters of Thomas and Hannah Groves written in the year 1851 when they visited London in order that Thomas should receive medical treatment for a growth on his face. We are very much indebted to Mrs Marjorie Rathbone (a great-great-granddaughter of Thomas Groves) for not only preserving these letters over the years but also for allowing the use of them for this article. When quoting the contents of the letters, spelling and punctuation (or lack of it) is as in the original.

Thomas was born on the 3 June 1789 and died on the 12 July 1860. The 1851 census shows Thomas and Hannah living with their family at Elms Farm in Shipton Road, Milton under Wychwood. He is described as a mason employing 16 men and a farmer of 12 acres on which he employed one man. His wife Hannah was born in 1792 and died in 1870. They are both buried in Milton churchyard. Members of his family, employees and local inhabitants are mentioned in the letters and a brief description of each one is given in the final paragraph of this article.

Thomas Groves visited Dr Batty of South Newington, Middlesex for treatment in the summer of 1851. He and Hannah were able to obtain lodgings in the Pegasus Tavern near to Dr Batty’s residence.

In an undated letter Hannah wrote: ‘we was much put to get lodgin we thought we couldnt get a bed in the place we pay 2 pound a week at this place your father is so well he has never been laid up one day since we have been from home that is a great comfort to me in a strange place’.

On 25 July Thomas writes:

‘Mr Batty informs me that he can cure my face’.

On 1 August he again writes:

‘I received Sarahs letter yesterday and was happy to heare you are all well and that Alfred is able to get out in the mornings I have named his case to Mr Batty and he say^.he must leave off those destructive pills He says he will send him something that will remove it’.

On 4 August he is obviously anxious about his mason’s business:

‘Have Alfred seen Harwood of Charlbury about the rim of the arch is the coping set on Upstones wall [Upstones lived at what is now Holly Corner, Upper Milton] Use plenty of lime in the foundations of the bridge’.

8 August:

‘Mr Batty has taken the lump off my face this morning they put in arches here like the one I have sketched [drawing of elliptical arch of the style used by Isambard Brunei when building the Great Western Railway a few years earlier] if the centre is made as I proposed’you will want 4 or 5 stiff pieces of larch large enough to make two it would be better to stand on edge 5″ by 8″ or 9″ and 20″ long Matthew had better do it be sure to have it strong enough’.

11 August:

‘I am pleased to hear you are getting on with the bridge hope you will endeavour to please Mr Bayliss’.

14 August:

‘Philip if you have finished at the quarry you had better get the harvest started but let it stand till ripe have Matthew finished The Carfax how does the old arches turn out’.

A very cheerful letter is dated the 21 August:

‘Dear Children, Pleased to hear that you are all well and that you have plenty of business and plenty of money and to inform you that we had £10 pound off Uncle Silman if Edward should come he may bring us some cash for this is a very expensive place’.

However a following undated letter was very much back to business:

‘Dear Edwin, I should be obliged if you would call on Mrs Edward if she has not been to pay her rent Also if John Miles and Richard should pay thers you must not give them anything back as we have to pay the takesis (taxes) and that is 8 or 10 shillings a year and ther rent is £3-3s a year and Mrs Edwards £3-10s’.

On 4 September:

‘Pleased to hear the bridge is making good progress should wish to have the ashlar for the parropet etc worked well as the season is rapidly advancing for using to much mortar Philip had better set on more men to get out more [stone ?] block if he takes on more men it may be getting dry and fit for use how is he coping with the harvest you may get the coping sawed for the bridge as soon as you can and some of the best dry block your coping on the wing walls will finish under the string courses Sarah will please bring me a warmer waistcoat’.

A very descriptive letter follows on 1 October:

‘I fear you will think we have quite forgot as I have not rote to you before my hand has been shaking that I could not rite We left Purfleet yesterday morn at 10 oclock by boat to Blackwall then took train and came to London took a cab and came to the Bank and took the bus I gave order to the conductor to put us down at Rathbourn Place instead of that he took us nearly to Camden Town we had to walk to Woborn Place took a bus then to South Place your mother was tired down we took a coop of tea and spent a very pleasant evening after a very tiresome day Send me a line today to say how you get on with the bridge if the plowing is wanting to be done get Pratts team plant some winter beans if you think best Tell Ellen you must let her please herself about staying with us another year’.

Evidently one of his men had an accident for on 31 October he writes:

‘Pleased to hear R Pitts is likely to occupy his place so soon and trust it will be a warning to him to fasten the ladder How are you getting on in the feild and in the quarry do not come from the quarry without a load of wallstones let them be chopt a little off the rough and be laid at the end of the house on the left of the stable door opposite Mr Bursons door or Alfreds shop Your mother says she shall want a great many loads when you have time you may draw some mortar by doing so you will oblige your affectionate Father & Mother T & H Groves’.

The good news came on 1 November:

‘I am just returned from Mr Batty and he says my face is perfectly cured of the disease I wrote tonight as I knew you would be very pleased do not talk much about it the less the better at present’.

21 November:

‘We intend coming home by the Moreton coach if we can if we cannot we must come by the other to the top of Burford Hill hoping that we shall arrive safe please send the rag cloak yours affectionately T & H Groves’.

These extracts are but a small selection of the total so carefully kept by Mrs Rathbone. The total lack of any punctuation and the rapid change of subject require them to be read very carefully. However, they do give a good idea of life 130 years ago.

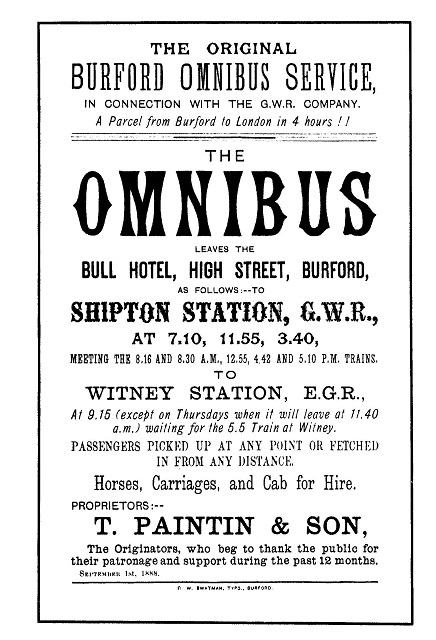

The remarks about the cost of living in London would apply equally well today. London apparently had quite a comprehensive transport system from the remarks made by Thomas when travelling by boat, train, cab and horsedrawn omnibus, even if the conductors were not too reliable. With today’s banking services it is easy to forget the problems of those days when one must have had to carry any cash that was likely to be needed.

Unfortunately I have yet to discover a great deal about the masonry work that made Thomas so anxious – I would particularly like to know more about his elliptical arches.

Of the names mentioned in his letters I have been able to discover a little more. George, his eldest son, was born on 25 September 1817 and died on 2 August 1886. He is buried in Milton churchyard. At the time of these letters he was married to Charlotte (nee Pargetter of Lutterworth) who was nine years his junior. Their first child, also Thomas, was born in May the next year and was followed by seven more children. At this time he shared a house with his brother Phillip at Upper Milton but later moved to Jubilee Lane. On his father’s death he took over the Milton quarries.

Philip was born in 1821 and also became a stonemason. He died on 9 April 1900 and was buried in Milton churchyard where his wife Mary, who predeceased him on 18 May 1860, was also buried. Sarah was Thomas’s only daughter. She married twice but had no children. She and her first husband, James Ellis, had a bakery and grocery shop in Milton High Street. They are both buried in Milton churchyard.

Edwin, the third son, was born on 20 December 1825 and was unmarried when he died on 13 April 1873. He had a tailor’s business in the High Street next to the Baptist chapel.

Alfred the youngest son, was born on 28 December 1826 and died on 16 January 1914. He is buried in the Baptist burial ground at Milton. Locally he is possibly the best known of the family as he carried on the family business as a stonemason at The Elms and formed the modern company of Alfred Groves & Sons. His first wife, Ann Shepard, bore him three children but died in 1855. His second wife, Mary Reynolds, gave him another ten children and thereby ensured the direction of the family business unto the present day.

Matthew was Thomas Groves’ younger brother, born in Shipton in 1796. He was a carpenter by trade and lived with his wife Ann Sophia Pratt from Leicestershire in Milton High Street next to the Butcher’s Arms. So far we believe they had three children, some of whose descendants correspond regularly with this society.

Ellen Miles was a living-in servant to the Groves family. Thomas’s remark ‘tell Helen she must please herself about staying’ was presumably a reference to the end of her year of service when a servant would then go to the hiring fair (possibly Burford Fair) to seek employment for the coming year. Thomas gave her the option of staying with them. Evidently she thought they were good employers and we can see in subsequent letters (not quoted here) that she stayed. Her parents Richard and Elizabeth (nee Puddle) were tenants of Thomas Groves and lived in a now demolished cottage on the site of Poplar Farm Close. From Thomas’s letter their rent was £3 3s a year.

The tenants quoted in these letters were John and Jane Miles (nee Hunt) who lived in Lower Milton. They were in their late seventies and obviously John was beyond working as a farm labourer as both were living on parish relief.

The last tenants to be noted were Thomas Edwards and his wife who lived in a cottage on the Shipton Road at Milton, possibly now part of the present house ‘Hoplands’. They were both newcomers to the village. They had three children and Thomas worked for Groves as a plasterer.

Information used to supplement these letters was obtained from:

Family papers in the possession of Mrs Marjorie Rathbone.

1842 Milton under Wychwood Tithe Returns.

1851 Oxfordshire Census.

Milton under Wychwood Graveyard Surveys compiled by Jack Chapman.

Acknowledgements are made to Roy Groves of Illinois U.S.A., Keith Barrie of Newport Beach, Australia and Keith Miles of Milton for information received