Here is an extended piece by Wendy and Jim Pearse, taken from the WLHS Journal No 15 (2000). We republish it here as part of an occasional series celebrating the work of the Society over time. (A PDF of the Society’s Journal No 15 can be found here).

The farming year begins in the autumn after harvest. The previous crops are carried and stacked and the land lies waiting, in anticipation of the next agricultural cycle.

October

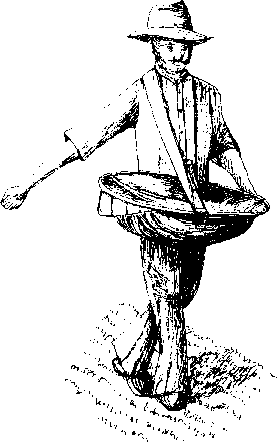

The sowing month for autumn crops. The soil has been ploughed and harrowed to a tilth suitable to receive the seed. Sacks of corn, a half peck measure, guide flags and a seed lip are taken to the field in a horse drawn cart. The sower can then set up his first flag near the straightest traverse of the field.

He begins his measured pace across the field, the seed lip of corn filled by the half peck measure, suspended from his shoulders by leather straps, each handful of seed cast in a sweeping arch in concert with the rhythm of his pace. Flags are regularly moved into position to guide his progress across the field.

The crop may be wheat, rye, beans or vetches and once the sowing is completed, horses will drag the harrows over the field to cover the seed. Hopefully soil conditions will be on the dry side, sticky mud on boots makes heavy going and several miles may need to be walked in one day.

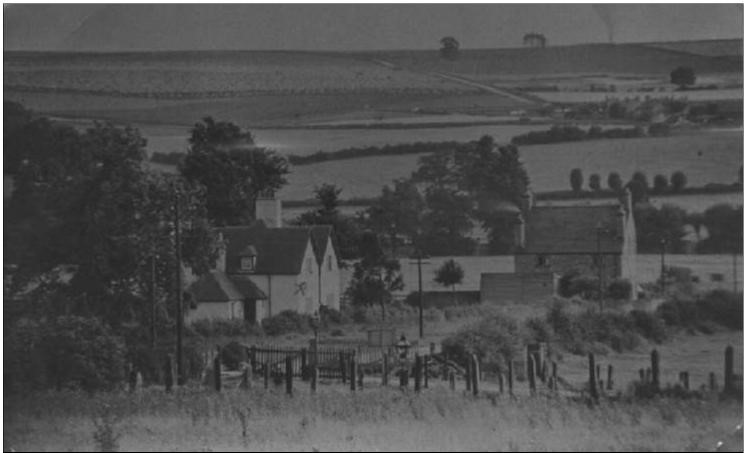

A number of trains run through the valley daily since the completion of the Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Railway only a year ago. During construction the necessary earthworks caused great disruption to farmers especially in Ascott where the line of the railway interrupted the access to their fields on the west and north sides of the parish and after a period of nearly eight centuries abruptly severed Ascott d’Oyley Manor from its associated village.

In the fields the sound of the trains approaching will compete with robins and wrens singing in the hedgerows. Rooks are not welcome – their voracious quest for newly sown seed will soon thin out the crop. At this time, potatoes for humans and mangolds for cattle are also harvested and the sheep are progressively penned with hurdles over the turnip fields.

November

With autumn sowing completed, the farmer’s attention turns to spring crops. Large heaps of manure cleared from cattle sheds during the previous year, which have been left to heat up and rot down, are loaded on to muck carts and taken to the fields.

Once unloaded into a number of heaps, the labourers can then use their four tined forks to spread an even layer across the land ready to be ploughed in. Robins frequently appear alongside the labourers, their bright eyes scanning eagerly for worms. Autumn fogs and frosts can create an eerie atmosphere to this task with steaming manure and the misty breath of men and horses rising up into the air.

This month also sees the harvesting of swedes for sheep fodder and carrots for human consumption. Maintenance jobs are undertaken. Road repairs, field drainage operations and the important winter occupations, hedge laying to maintain stockproof hedges and ditch clearing to ensure the free flow of field drains.

December

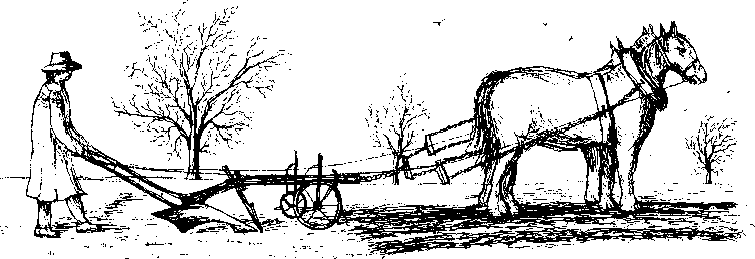

The month for winter ploughing. Although the use of individual strips to denote ownership is no longer required due to the recent enclosures, the time honoured practise of maintaining the ridge and furrow system is still continued. Ridge and furrow aids surface drainage and ensures at least a reasonable crop on the ridges in a wet season and the furrows in a dry season.

The ploughman will position his ploughteam, probably horses but oxen may still be used, on the field headland in line with the first ridge. The first plough furrow will be cut along the top of the ridge, the share making the horizontal cut about five inches below the surface while the coulter makes the vertical side cut and the mould board turns the furrow slice over to the right hand side of the plough.

The ploughteam proceeds around the ridge in a clockwise direction ensuring the soil is turned uphill to maintain the ridge. The ploughman needs to keep a firm grip to steady the plough against the thrust of the soil which will tend to force the plough sideways downhill.

When the ploughing on this ridge is completed and the furrow opened, the ploughman will commence on the top of the next ridge. The headlands will be ploughed last to complete the field. An acre a day will be the ploughman’s aim in which time he will walk about ten miles.

During ploughing rooks may perform their only deed of assistance to the farmers. Following closely behind the ploughman, they will consume from each furrow, quantities of wireworms and other insect grubs and larvae which would otherwise remain active in the soil and cause damage to the spring crop. Hopefully the ensuing months will bring some frost and snow to break down the soil to a fine tilth to form the seedbed for the spring corn.

Throughout the winter, cows, calves and fattening cattle will be kept in stalls and yards, their foodstuffs carried to them at regular times during the day. They will also need to be provided with a supply of water and bedding straw.

January

With land work possibly held in abeyance by the weather, threshing the last season’s crop is the main occupation for the agricultural labourers in the large threshing barns. A sheaf of wheat is spread out on the threshing floor and two men working to a rhythm alternately beat the ears of corn with flails, to knock out the grains. Certainly not an easy task and one that requires a large amount of elbow grease.

Once the ears are empty, the straw is collected and stacked and the grain is shovelled up ready for winnowing. The high wide doorways not only give access to horses and waggons but create a good through draught which is part of the winnowing process. Shovels of corn are thrown up into the air so that the draught will blow the dust and chaff away from the grains.

Threshing and winnowing are hard monotonous tasks lasting several months but necessary to acquire the new seed to sow, animal feed and grain for sale.An alternative job during drier spells is the spreading of very short well-rotted manure on pasture land to aid early spring growth of grass.

February

Fills the dyke, either black or white. Often the month causing the most awkward and difficult conditions for man and beast. Frost plays havoc with water supplies when it is essential to satisfy the thirst of all farm animals. For some obscure reason cattle especially seem to drink more in frosty weather. Frozen mangold clamps cause problems with sheep fodder. Eggs crack in the nestboxes of hens. And any delayed land work can be impossible to pursue, especially when temperatures remain constantly below freezing.

Snow causes problems with movement of animals and other goods and roads may become impassable or slippery. It may be necessary for the horses to be fitted with snowshoes – a type of horseshoe with protruding nails that gives a horse some measure of grip in snow and ice.

This month may well be an extremely busy time for blacksmiths since the shoes will need to be changed as required, depending on the variations of the weather.

March

The busiest time of year for shepherds and a fickle month for weather – cold, wet, windy or all three. Time to build a lambing pen, constructed of hurdles, windproofed with straw cladding and well-littered with bedding straw. The more protection provided for the new-born lambs, the greater the number that will survive and as shepherds are often paid per lamb, a successful lambing season is important for both shepherd and farmer.

Shepherding is a lonely job with little sleep during the peak of the season, the shepherd continually patrolling his flock using only the soft glow of his horn lantern to avoid scaring the ewes. Odd moments are spent in his hut or shelter where a drop of whisky and warmth will possibly revive the shepherd as well as poorly lambs.

March is also the month for spring sowing when all types of crops are sown including oats for horse feed, barley and carrots for humans and grass, clover and vetches for hay.

April

When many crops are beginning to germinate in the fields, the blight of the farmers’ lives is crows, rooks and jackdaws. With young birds in their nests to feed, a continual shuttle service is carried out by the parent birds which in a large flock can decimate a corn crop in a matter of days.

The prime deterrent is a crow scarer, preferably human, a young lad with a rattle and a loud voice. Not a pleasant job by any means, cold, tiring and monotonous and very poorly paid, but an extremely necessary addition to the farming structure.

Another type of aid comes in the form of peewits (lapwings or plovers), the farmers’ friend. Peewits nests with eggs will be left carefully undisturbed amongst the emerging crops because of the parent birds’ determined protection of their young.

At the sight of an approaching marauder (rook or crow) they will soar into the air and fearlessly dive at the predator until it retreats. A field with two or three peewits’ nests can be left to the birds to defend.

With the remaining crops of potatoes and mangolds safely planted, attention turns to livestock. The larger cattle will be turned out into the pastures and horses and carts will transfer the manure from pens and sheds to the expanding heap in the field.

May

With a fresh growth of spring grass and herbs in the pastures, the young calves can be turned out. Here they can exhibit the natural exuberance of the young and free, by all means of exercise, racing, jumping and kicking up their heels with pure pleasure before settling down to experience the new sensation of eating fresh young grass. With bulging sides and tired limbs they can, at the end of the day, retreat to their resting shelters and chew their cuds, enjoying the grass for the second time.

But farm labourers are less fortunate at this time since a major monotonous occupation is the elimination of weeds in the crops. It is performed mostly by hand, hoeing through long hours of daylight, although some horsehoes may be used in the root crops. Some consolation is the rippling song of numerous skylarks rising and falling overhead.

June

The hoeing of crops continues and turnips are sown for autumn feed for sheep. But now is the time for shearing the sheep when the rise in the wool indicates the natural time to shed the fleece. Washing the sheep in the wash pools ensures a clean fleece which fetches a higher price.

But whether the loss of dirt will reduce the weight sufficiently to negate the extra value is debatable. Washing which involves rubbing and squeezing to rid the fleece of as much dirt as possible occurs several days before shearing and both processes are accompanied by a tremendous amount of bleating from lambs who are temporarily separated from their mothers, to keep them out of harm’s way while their mothers are attended to. Hand-shears are used, a skilled man can shear four sheep in an hour.

Occasionally a cut will occur which is instantly treated with Stockholm tar to cauterize the wound. The fleeces are rolled and tied and packed into woolsacks ready for dispatch to the buyers.

July

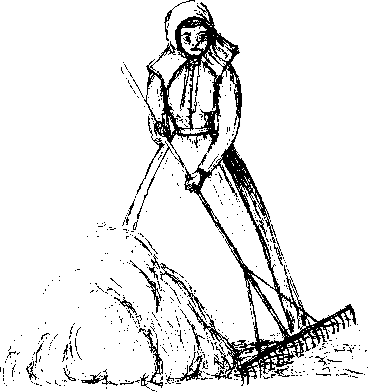

If the weather is favourable, haymaking will begin towards the end of June, but is in full swing throughout July. The grass is mown by scythes. The labourers work in line cutting a swathe of grass which is left behind each of them as they work across the field. Now women and children take over.

The swathes are spread thinly over the ground to ensure maximum exposure to sun and wind. Later the grass is raked into smaller rows called wallies which are frequently turned to allow the moisture to evaporate until the crop becomes a sweet smelling, rustling hay. Throughout this process the fields are alive with several varieties of butterflies seeking pollen and nectar from the wild flowers and herbs growing amongst the grass whilst swallows and swifts fly overhead.

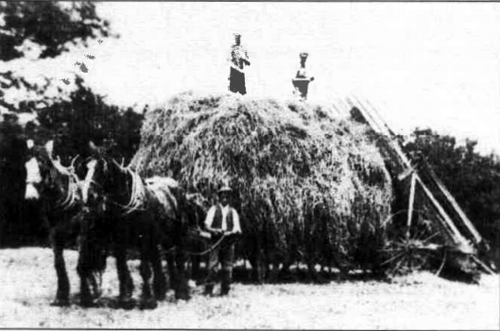

The hay is raked and built into rows of cocks – small stacks of hay as much as a man can lift on a seven foot pitchfork up to the waggon. The horse and waggon are then led between two rows, a pitcher goes to each row and one man on the waggon to build te load. No one leads the horse. His or her name is the command to move forward and whoa is the word to stop. When the load is completed and roped, the horse and waggon are led to the rickyard where the hay is built into ricks.

The amount of time required for haymaking depending on the quality and age of the grass and hopefully dry weather varies from three to seven days. Spells of rain can double the making time.

August

Like haymaking, harvesting is an extremely busy season. All hours of daylight are used, sometimes under extreme pressure. The weather can suddenly turn into the enemy.

When conditions are right with both corn and weather, scythes are once more to the fore. A bow (similar to a chair back) is fitted to the scythe for harvesting. This carries the cut corn round to form the swathe instead of allowing it to fall over the handle. Barley is normally left loose and carried similarly to hay. But wheat and oats are tied into sheaves by women and children with straw bonds made from the crop, then stood into stooks by the men, each stook of six sheaves supporting each other. These are then left to get thoroughly dry.

Oats should have the church bells rung on them at least three Sundays. Finally the sheaves are carried to the rickyard whilst opportunist kestrels hover above the newly cleared fields seeking the now less protected mice. The ricks are built with all the butt ends to the outside beginning by working round the stack from the middle with a deeper layer in the middle to cause a natural slope to the outside.

Once the crop has been carried, the fields are opened to the gleaners – the poor people of the district who are free to take part. Every loose ear is a bonus – free food for hens and pigs or it can be threshed to be ground into flour.

September

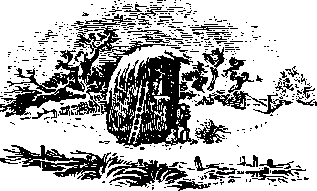

Harvest complete, it is important to maintain the quality of the corn by thatching the ricks as unthatched grain will quickly sprout under wet conditions. The yealmer shakes ready-threshed straw into a heap and dampens it for strength. A number of handfuls are pulled out and using his fingers he combs the straw to form a yealm – a thatching unit. The yealms are laid in alternate directions in the angle of a forked stick – a jack. When full the jack is carried on the yealmer’s shoulder to the rick, where the thatcher carries it up the ladder to the top. He begins at the eaves and tucks the thinner end of the yealm into the roof. Then the next yealm is put in with the big end, the thinner end overlapping the first yealm. He continues to lay the yealms up the roof until he reaches the very top.

Now starting from the top and working downhill, he combs the thatch out straight with a hand rake and fastens it down with a bond or twine held into place with sprays (rick pegs) three feet long made from split ash or ha el. Up to a dozen lines of twine and sprays will be arranged across the roof. A good overhang at the eaves and gable ends will give better protection from the weather.

In preparation for the next sowing season, the clover land is manured and ploughed to enable it to settle before wheat planting takes place.

And so the farmers’ year is complete. Twelve months of wind, rain, snow, frost, hail and sun, wet days and dry spells have passed. Another sowing, another harvesting and a new crop of calves and lambs to tend. Long days, and nights of hard earned sleep, and now the next year of unknown fortune lies ahead.

Reference:

Pamela Horn, Labouring Life in the Victorian Countryside.