Speaker: Maurice East

Subject: “Down in the Dumps” – How Oxford Helped Win World War Two

Another fine evening was enjoyed by 40+ members and guests, with plenty of response at the Q&A from many of us who had family connections with the Cowley works. Maurice is a speaker who is clearly passionate about Cowley’s role over time, and his talk was full of surprises, only a few which we illustrate here.

Introduction

Maurice started the evening with a discussion of the role of Oxford in the nation’s consciousness and the myths around its contribution or otherwise to the war effort in World War Two.

He played a BBC excerpt from the programme “Rogue Heroes” which exemplified the usual idea of war heroes. However, as he pointed out, all their equipment and weaponry was actually manufactured by equally committed individuals who are far less lionised.

And so, the theme of the evening was how the contribution of the Cowley Motor Works became instrumental in the war effort in a way which is often underestimated.

William Morris and Morris Motors at Cowley

Maurice covered the development of the Cowley works through the story of William Morris and his creation of a major manufacturing business from early beginnings. [ A story also told here : Morris Metropolis ] . With the advent of World War One, William Morris’ enterprise engaged in war work. This included the making of mine sinkers for the Royal Navy in large quantities.

After the First World War, in the 1920s there was a major expansion. This included, in 1926, the building of the Pressed Steel factory which created a huge demand for labour. Men came from all over the UK and especially from South Wales, building the centre of gravity of the population of Oxford eastwards around the villages of Barton, Headington and Iffley amongst others.

By the outbreak of World War Two it was clear that the country was ill-prepared and short of arms and equipment, especially of aircraft for the Battle of Britain. At the nation’s low ebb, Dunkirk, things looked bleak.

Wartime Production at Cowley

But as these concerns grew, William Morris (Now Lord Nuffield) acted. In the late 1930s, his company began developing tanks and aircraft engines. When war erupted, the vast Cowley factory transformed once again, this time into an armaments and military equipment production hub.

The output ranged from army trucks, utility vehicles and light reconnaissance vehicles to Cruiser and Crusader tanks. Additionally, the factory produced aircraft components such as engines for the Lancaster bomber, as well as wings and tail units for the Horsa glider. By 1940, Cowley was also making complete Tiger Moth training aircraft for the RAF.

Everyday military essentials, such as wireless communication devices and searchlights, also rolled off the assembly lines – not least, millions of helmets and field canteens for the army. Extraordinarily also, in the field of neurosurgery, the production of metal plates used in surgery for head injuries pioneered by surgeon Hugh Cairns.

Beyond “Production” at Cowley

However, the Cowley factory’s role extended beyond production, and this was a key theme of Maurice’s talk, with extraordinary and copious illustrations of recycling and re-purposing materials from crashed aircraft, both allied and German.

Given the chronic shortage of planes, restoring damaged aircraft was crucial, allowing them to return to the front lines. To manage repairs across the country, the government established the Civilian Repair Organisation (CRO) in secrecy, coordinating repairs in a network of factories and workshops. Lord Nuffield was invited to lead the CRO, initially based at Cowley but later relocated to Merton College in 1940. Repaired sections of aircraft, and sometimes entire planes, were transported to airfields for reassembly and test flights

The Cowley factory specialised in repairing crucial Hurricane and Spitfire fighter planes, along with trainers produced by Miles Aircraft and the Tiger Moths they manufactured. During the intense three months of the Battle of Britain in 1940, the Cowley Unit restored up to 150 planes to active service.

To improve efficiencies and expediate repairs, Cowley Airfield was constructed adjacent to the factory. We even learned that damaged planes were occasionally flown directly to the airfield for “while you wait” repairs, swiftly returning to battle.

We also learned that Cowley served as the hub for a civilian salvage group (50MU), operating seven days a week to collect and transport damaged aircraft and parts for firms participating in the CRO network. Over the course of the war, this unit handled upwards of 12,000 aircraft. Maurice showed us extraordinary pictures of the transporter vehicles used for this work.

However, not all recovered planes could be repaired. The Morris factory housed a “Metal and Produce Recovery Depot” (MPRD), which salvaged badly damaged aircraft from various nationalities for parts and raw materials. For this work, the extraordinary “Cowley Dump,” a sprawling area of mangled wreckage from severely damaged planes, covered 100 acres of adjacent farmland.

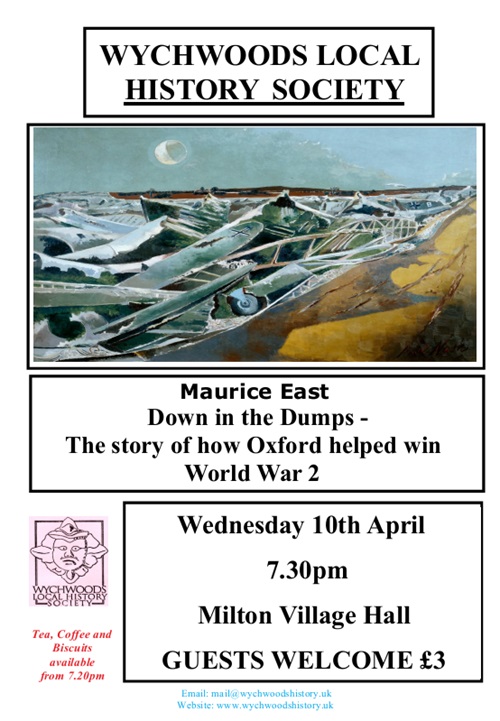

These twisted metal piles, organised in blocks and “roads” for easy access, were immortalised in Paul Nash’s 1941 painting titled Totes Meer (Dead Sea), displayed today in the Tate Gallery. Thousands of tons of high-grade aluminium, rubber, steel, and plastics were reclaimed and reused as part of this programme.

By the end of the war, Cowley had more than twice as many employees as it had before the war. Most of these workers were women because of course most of the men in the regular workforce had been drafted into the armed forces.

It was a great blessing that Oxford and the Cowley area was never damaged by bombs. But clearly the workforce at Cowley were instrumental in the eventual victory for the Allies, risking its own set of dangers with commitment, imagination and effort. Maurice’s talk was an eye-opener and indeed pointed to another – and very important – definition of wartime heroism.

About Maurice East

Maurice East was born and raised in Headington Quarry at a time when everyone you met seemed to have a connection to the car factory. His father, grandfather and uncles all worked ‘on the line’. After living in London for many years he returned to Oxford in 2013 and found a city much changed by de-industrialisation.

During lockdown he used his love of local history to develop walking tours which deliberately avoid the typical tales of dreaming spires and instead seek to reflect the overlooked experiences of ordinary Oxonians. This is history from below, less grand but no less exciting. The story of how Cowley helped win World War Two is one of those hidden stories of Oxford.