The following article by Alan Vickers is based on the written notes of Jeff Broxholme, who has lived at Milton under Wychwood since 1969.

An idyllic Life – Living by an old Oxfordshire Mill before and during the Second World War

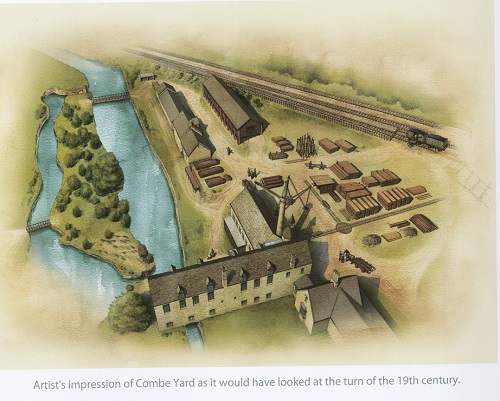

His family lived very simply but Jeff Broxholme still remembers his early life at Combe Mill with affection. Combe Mill is in a valley midway between Long Hanborough and Combe Village in West Oxfordshire. The Oxford Worcester railway shares this valley with the River Evenlode. Combe Mill is mentioned in the Doomsday Book but was probably not as large as it is today. It is assumed that this earlier mill was a flour mill, powered by a water wheel on the River Evenlode. It has greatly changed since that time. Even the original village has disappeared, possibly because of the Black Death. It is said to have been relocated to the top of the hill where the present village stands, about one mile North of Combe Mill. There are no remains of the original village except for a mound where the church stood. This is on the left near the top of the drive from the road linking Long Hanborough with Combe.

The drive itself leads to the Blenheim Estate Maintenance Yard. It passes two cottages where Jeff Broxholme lived until he was eighteen years old. Part of the first building on the left was a saw mill, in use until around 1980.

His father, Stephen Leonard Broxholme (always known as Leonard) was born in Ragby Lincolnshire in 1901. He worked as a sawyer in the local sawmill until 1927 and then moved to Heythrop to work in the sawmill there. In 1930 he married the housekeeper and cook of the Rectory at Cornwell, Emily Selina Hands from Chipping Norton and needed a house for his new family. He found a position as manager of the sawmill on an old estate yard belonging to the Duke of Marlborough in Combe and moved there in 1931. Jeff was born in the same year and his sister Edith Marina followed in 1934. Jeff’s father was the only sawyer at the mill which was very run down following the First World War and the depression of the 1920s. He was to work there from 1931-1949 cutting timber from the Estate Woods for use on the Estate – planks, posts, rails and oak coffin boards for Blenheim Palace.

Early Life

Jeff’s early life was somewhat precarious. At first the family lived in a small thatched cottage in the hamlet of East End Combe. When he was only two, a beam above the cottage fireplace caught fire which spread to the thatch. He still recalls the flames and reflections off the firemens’ helmets. He was taken to another house in the hamlet. His mother was rehoused with a friend nearby. Shortly afterwards the family moved to Combe Mill. There he suffered a series of illnesses, possibly due to the poor water quality at the Mill. At first he developed a large swelling in the neck and had this operated on at the Radcliffe, travelling there from the new railway halt at Combe. While recuperating he took some water to drink from a bucket at Mrs Williams’, friends of his parents who had helped them following the fire. He slipped and fell on the edge of the bucket undoing all his stitches. Somebody with a car took him back to the Radcliffe. Later he spent time in the isolation ward at Abingdon with scarlet fever.

Life at Combe Mill

Food was never in short supply. Leonard always had a fried breakfast before going to work. Eggs came from their own chickens. A very impressive cockerel attacked young Jeff but disappeared very shortly afterwards, presumably via the pot. Rabbits and hares could be caught but game birds belonging to the Estate were strictly off the menu (hardly surprising when a gamekeeper was summarily dismissed after a day’s shoot just failed to reach a bag of one thousand birds!).

Occasionally there were shooting parties from the Estate in the vicinity of the Mill and Jeff’s home would be used for luncheon if required. The servants brought the food in hay boxes. The ladies used the house for powdering their noses – how they got on with the Elsan earth toilet in the garden is not known!

There were domestic rabbits too whose numbers were increased by taking the does to the buck in Long Hanborough. Two pigs were kept in sties at the back of the house. One was killed in March and one in November by the local slaughter man. A straw fire would be lit to burn off the bristles and the carcase hung up to bleed. Milk was delivered from Richard Colliers’s farm along the lane. Although the river was close by, fresh fish did not figure on the menu although occasionally eels were caught and eaten and their skins used for shoe laces. In season, blackberries and hazelnuts could be gathered from the hedgerows close to the mill.

Bread and meat were delivered. The meat came from a butcher in Woodstock. Bread was supplied by the two bakers in Combe. One, Mr Pott, did not have a van and walked everywhere with a large basket. He also delivered telegrams and cooked meat for private households on Sundays. The Coop could be reached by bicycle to Long Hanborough. Some groceries came in Walford’s van from Bladon and there was a small grocers in Combe, Teddy Busby Stores. The Combe Post Office also served as a general store. Brookes stores, also in Combe, supplied sweets. Clothes were ordered at Strong and Morris in Woodstock but sometimes items were obtained from Banbury.

Mrs Broxholme made a wheat and potato wine. Other sources of alcoholic beverages were the three public houses which existed at that time in Combe village – the Cock (still in existence today), the Royal Oak and the Marlborough Arms. The Royal Oak suffered a setback when the landlord, Mr Muggeridge, killed himself by jumping off a railway bridge into the river following irregularities with the Christmas fund.

Heating the home was not a problem as the family could burn the offcuts from the sawmill. The same energy supply served for cooking. Electric power only came to the cottage in the 1950s. Light was from paraffin lamps or candles.

Entertainment was from a battery powered radio bought just before the War and attached to a long wire aerial. New batteries were sourced from Woodstock when required. There were no holidays but only the occasional bus trip to the coast, mostly to Southsea which was the closest point on the coast. A train trip to Chipping Norton to visit his maternal grandparents was an infrequent pleasure. This would be either in a diesel car or on a steam train where the driver would sometimes allow you to stand on the footplate. At Kingham one had to change and go over the covered bridge to catch the train to Chippy.

School Life

Jeff started his formal education at five years old in the infant department of Combe School. He would be taken the one and half miles on the back of a bicycle ridden by his mother. Because of the earlier injury to his neck, he was always reminded to take extra care and could not take part in sports or games so that he felt isolated from his schoolmates. There was no hot food at school. Most children went home at midday. Some, like Jeff, who lived some distance from the village, were allowed to stay in the school and eat their sandwiches. A large white card was hung on the school gate and the children could not re-enter the school until this was removed. Jeff would be picked up again by his mother at the end of school. In the meantime, his father kept an eye on Edith, sometimes with the help of a neighbour, until his mother got back.

The School comprised two classes and served around 35 pupils. Mrs Woodward looked after the infants (aged 5 to 7). Jeff was one of the smallest children and was put next to another small boy, Derek Allan, at the front of the class. Next door, the Head teacher, Miss Walker, had four different classes in one room – 7 to 8 year olds, 8 to 9 year olds, 9 to 10 year olds and 10 to 11 year olds.

The ultimate disciplinary sanction was the cane across the hand. Jeff remembers the cane breaking on the hand of a boy called David Oliver.

At the age of eleven, those, who had passed the Scholarship, went to Chipping Norton Grammar School. They cycled to Stonesfield (on bicycles apparently provided by the Council) where they caught a bus. Jeff went instead to the Marlborough Secondary Modern School at Woodstock. Prior to this school being opened in 1939, village children who did not pass the 11+ went by bus to the bigger school in Church Handborough.

The keepers saw to it that there were no raptors in the neighbourhood but Jeff remembers other wild life – otter spraints on the concrete strip near the mill, water voles and lots of hedgehogs. Strangely he does not recall seeing wild ducks but one year there was a wild goose down by the river although this disappeared just four days before Christmas!

The Village Calendar

An important village event was the celebration of Mayday. All the school pupils were taught various dances. The older girls had to decorate an old bath chair with flowers to form a suitable carriage for the May Queen, chosen, along with a May King, by the Head teacher, Miss Walker. This carriage was pulled around the village and a collection made for some unspecified purpose. The girls wore flower patterned dresses with bonnets. The boys had hoods extending over their shoulders in green cotton and long green buttoned coats reaching nearly down to their knees. Costumes were made by Miss Walker’s mother who lived with her in the school house. After the dancing on the green, there was a tea party and sports.

The first Sunday after 10th August was the Combe Feast. There was a funfair often with steam engines, on both village greens.

There were other flower and vegetable shows, which were usually held in conjunction with a fete and sports. These took place either at “Combe House” or at Mrs Cottrel Dormer’s in the middle of the village. Jeff’s father won many prizes for his vegetables and Jeff and his sister usually won certificates for wild flower displays.

At the end of the school year, there was always a school play where Miss Walker attempted to involve every child.

The Second World War

At Sunday school one day, Jeff learned that “there was a war on”. When he got home, his father confirmed this. Jeff asked who he was going to join, “the cowboys or the indians”!

With the outbreak of war the pupils were told to stick brown tape to the larger windows of the School. They were issued with a gasmask at home. This was a trunk like contraption with an eyepiece to look out from. The lower part comprised a flat metal attachment which was adjusted by the man who had brought it. The whole thing smelt strongly of rubber. Later everybody had to go to The Royal Oak Public House and line up by a large table to have another bit fitted to their gas mask. The lower part was green and it was fitted by means of some special sticky tape. Apparently this new bit contained charcoal. Gasmasks were kept in a brown cardboard box with a string handle so that they could be carried over the shoulder. This later wore out so a tin tube with a lid and string handle had to be bought to replace it. There were frequent practices at school in putting on the gas mask. Sometimes the eye piece misted up and the Head teacher told the children to rub some soap on the inside of the mask. Great fun could be had by blowing effective raspberries from inside the mask. There was no explanation as to what the brown paper or the gas masks were for. Similarly the children did not know why they were asked to bring cans to school and then hammer them flat.

Many evacuees came to Combe and the surrounding area. They brought their own school teachers. One day two ladies appeared at the Mill with five children from Enfield in tow. The Broxholme family were required to house them – the French family of three (two girls, Betty and Ruth and one boy Derrick) and one boy (Peter) and one girl (Beryl) from a family called Carr. Peter and Derrick took the bus each day from Combe to Marlborough School with Jeff. This unexpected supply of playmates was welcome to Jeff and he does not recall any special friction between the children. They delighted in playing in the surrounding woods and there were Leonard’s wonderful sledges to play on in the winter.

Canadian soldiers were billeted at Blenheim Park where cattle and some lambs were said to have ended up on barbecues. The Americans were based at Brize Norton and Heythrop and consequently black troops were a rare sight in Combe. There were few British camps close to Combe apart from one at Finstock (the concrete remains are still visible close to the Garden Centre.) Freeland housed a military hospital.. There was a satellite airfield at Kingswood where Spitfires were hidden in the woods.

In the direction of Charlbury, there was a grass strip and a tin hangar housing a Liberator for the personal use of Winston Churchill who was a frequent visitor to Ditchley House.

Actual military activity was hardly in evidence – a few incendiary bombs falling on Stonesfield and Bladon and a Bren Gun Carrier which became stuck in the river close to the Mill. The four Coldstream guardsmen from the Bren Carrier spend six weeks living in the Mill yard stables. Jeff and the evacuees helped clean the river mud off the bullets. His mother did all their cooking and even interceded for them when their officer would not let them go to a local dance!

The closest form of military power was the Home Guard. Jeff’s father was a member of the Combe unit. Some of the exercises closely resembled an episode of Dad’s Army. For example, on one occasion, the Combe unit managed to penetrate the defences of Brize Norton by using a false floor in a lorry. On another famous day during an exercise which pitted the Combe Home Guard against the forces of Long Hanborough, the Combe unit prevailed when the whole village population turned out and helped arrest the Long Hanborough contingent!

One night Leonard took Jeff out to Combe Hill rise to show him the glow coming from the bombing attack on Coventry.

Leonard Broxholme served in the Home Guard until he had a serious accident. Walking in the blackout to Combe for a Home Guard meeting, the handle of his canvas shoulder bag was caught by a passing car and he was dragged along. He lost an eye and one arm was so damaged that he did not regain the use of it until 1963 when a pit bonesetter in the North of England worked a miracle that was apparently beyond conventional medical practioners in the twenty years since the accident occurred.

Just before D-Day, there were manoeuvres between British and American troops around Combe. Telephone wires were laid in the fields from the back of trucks. Afterwards the wire was carefully harvested by the children just as they had done throughout the War with the aluminium strip broadcast to confuse the enemy radar. This wire made much stronger reed boats than had been possible before the War.

The children did not receive regular pocket money but earned cash by collecting flattened tins and rose hips for the war effort. Rose hips at three pence a pound were particularly worthwhile.

All the children were issued with Wellington boots during the war. Prior to that, wet socks had been hung up around the Tortoise stove in the classroom.

In 1943 Jeff joined the Scouts and stayed with them until he was 19, eventually becoming a Kings Scout. It rained on his first camp but the scoutmaster lit a fire and prepared a hot drink and supper. Sacks of straw were obtained from a farmer and these became the boys’ beds on the groundsheets. The scout movement became a window to the world beyond rural Oxfordshire when he went to France and Norway with the scouts in the late 1940s.

Members of the Red Spinning Society, a fishing club for London businessmen, would sometimes come down for a weekend of fishing. They would be looked after by Mrs Broxholme. Jeff recalls some splendid characters among the visiting members. A Mr Panyey had been to America and could spin a rope like a cowboy. Another used to bring a microscope and entertain the children with the results from his pond dipping among the reeds. Some were wonderful conversationalists who could conjure up something of life beyond rural Oxfordshire.

Later Career

Leonard moved to the Eynsham Estate in 1948 and worked in the saw mill there until the Mason family lost much of their fortune through the collapse of copper prices. Leonard then worked in Woodstock for Scarsbrook before finally joining the timber department of Groves the builders in Milton under Wychwood in 1954. Jeff became an apprentice carpenter at Tolley Brothers of Bladon in 1945. After two years of National Service with the RAF, He came back to Chipping Norton to work with a former colleague who was setting up as a jobbing builder. In 1954 he too joined Groves in Milton, working as a bricklayer charge hand.

The Mill in Detail

Cut timber was stacked on the right hand side of the drive to dry. Planks were left for seasoning underneath the carpentry shops. Some oak boarding was kept at Blenheim for coffins (including probably Winston Churchill’s) The planks and rails had small laths of about 1 1/4” by ½” placed under each piece of timber. It was reckoned that each ¼” of timber needed a year to season.

The timber in the form of tree trunks was brought by contractors, often using Foden steam lorries, and was placed where a small wooden crane (a derrick) could lift them onto a steel plate to be moved to a large circular saw blade. This crane was operated by hand with a winding handle and pulled diagonally as required by a second operator. If the log was too long, it had to be cut by a crosscut saw, a two handled saw blade operated by two people. Jeff remembers seeing his mother use the blade when no other person was available.

The mill was powered by a water wheel driven by shafts and pulleys through a blacksmith’s shop connecting with the main machinery under the saw mill. The water wheel, which is still in place today, was quite large, approximately 13 feet diameter by 8 feet across. It was converted in 1850 to saw mill use (source Oxfordshire Mills by Wilfred Foreman published by Phillimore 1983). The wheel was “breast-fed” ie the water hit the wheel midway between the top and the bottom of the wheel. The resulting power was well used. The first use was for a water pump taking water to the roof of the building where it filled a large tank supplying the adjoining cottages. This was only river water and was not for drinking. There were taps over the kitchen sink and also a copper in the wash house. (Drinking water came from a spring on the other side of the river, about 150 yards away. Two buckets had to be fetched before breakfast.)

The next use of the power from the water wheel was to turn the fans in the blacksmith’s shop. This was followed by power to the band saw in what was called the “pattern shop” on the first floor. The cogs for the pit wheel and pinion wheel were made from cast iron coupled with wooden cogs made from hornbeam.

The fourth use of the power was to the sandstone wheel used by foresters to sharpen their axes.

The fifth use was to a large lathe, used mainly to cut the hubs of cart wheels some of which could reach 15”” in diameter.

The sixth power offtake was to the saw mill itself. This was in the form of a continuous belt to a rack of belt pulleys powering respectively:

- A small carburundum wheel for sharpening saws

- A planing tool with a blade of approximately 15” wide, installed around 1944

- A large saw between 3 to 4 feet diameter

- A steel plate (called a rack bench) for bringing tree trunks from outside to the saw for ripping. The derrick crane previously mentioned lowered trunks onto this plate.

- A belt from the steam beam engine (discussed below)

- A small saw of approximately 30 inches diameter for a hand push bench for much smaller pieces of timber

The steam engine was installed in about 1852 It was used when river water levels were too low following drought or when there was too much water because of flooding. This double acting, condensing, rotating beam engine was only therefore used intermittently between 1852 and 1913 and was in good condition when laid up in 1913. It was left in a locked room until the early 1940s. An auxiliary steam engine was installed during the First World War to cope with the additional throughput of timber needed for pit props and trench supports for the War Office. This was a coal fired agricultural tractor with belt drive. Jeff remembers this engine falling apart during the 1930s and it was probably scrapped around 1936.

The water wheel was in poor condition and required a new shaft when Jeff’s father arrived. He arranged for this to be produced at his previous sawmill in Heythrop. The mill workings were generally in bad condition – pully shafts were often missing and wheels had to be replaced. Brass castings were obtained from Daniels in Bridge Street Witney. Heavy mechanical work, including work on the waterwheel, was carried out by Johnson and Son of Standlake. Once the new main shaft for the waterwheel had been installed more people were engaged at the Combe Mill. An assistant, Mr Margates was taken on to help Leonard. Tom Knibbs was the carpenter working in the shop. He was the son of the landlord at the Cock Inn in Combe. A blacksmith, Bert Horn, came in from Bladon when required. A painter lived next door to Jeff’s family. The foreman for the estate yard was Charlie Townsend.

The company was completed by a horse named Jolly who could be harnessed to a cart for deliveries. A full time stableman from Long Hanborough looked after the horse and made the deliveries. The water wheel was used until the 1950s when electric power was installed at the Mill.

The chimney for the beam engine had been knocked down around 1922. As it was only of brick construction it was easily dismantled. Most of the bricks were simply dropped down inside the chimney.

The later Restoration of the Mill

Jeff was first approached by a group interested in restoring the mill chimney in 1968-69. He completely stripped down the old chimney and built a new one which has a date plate for 1972 fixed on the West side. The new chimney was first used in 1973 when the restored beam engine was fired up for the first time and Leonard, much to his delight, was able to witness this not long before his death in 1977. The restoration group was surprised to see how fast the engine fly wheel ran.

The original boiler is still in place but would no longer withstand the required steam pressure. A subsidiary boiler was installed and is used at the present time. The original boiler is of the Cornish type, consisting of a horizontal cylinder or drum and was installed at the same time as the engine. It is thought to be one of the oldest boilers in the country still capable of use.

The mill race was blocked up by the Estate but a small reservoir of water has been installed by the restorers. Water is pumped from the river to provide some motion to the wheel. The original sluice gate was also unfortunately destroyed by estate workers in the period 1965-1975. The water run from this sluice gate had produced an enormous hole in the river bed with a pool of 40’ diameter and 8’ deep, ideal for boating with reed boats, swimming and diving.

The mill building has now been restored thanks to a Lottery grant and is protected as a Grade II listed building. The restoration included the provision of a lift for the disabled. The Mill is now open for visitors and is in steam from March to October on the third Sunday in the month. Here is The official Combe Mill Website