“That’s How it Was” | Introduction | Wychwood Women : The Interviewees | Declaration of War | The Arrival of Evacuees| School Time | Preparing for War at Home | Soldiers and Airmen | For the Common Cause | Dr Scott and the Canteen | Domestic Life | We Were Lucky Out Here: Food Rationing | Work for Women Outside the Home | The Effects of War

… from the Wychwoods “That’s How It Was” Publication

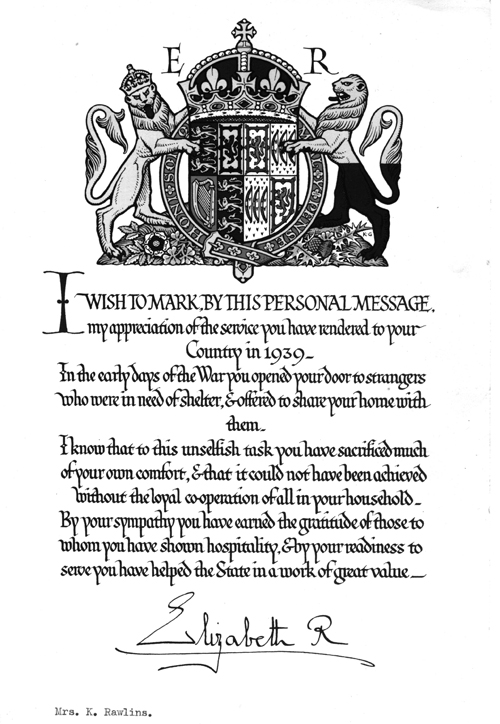

The government had prepared for large scale evacuation of children from cities to safer country areas so billeting officers enlisted the help of Wychwoods WI for billeting surveys of every house that could take in evacuees. After Chamberlain’s return from Munich in 1938 with the hope of peace, these preparations were put on hold. But, by 1939, the hope had faded and the remaining gas masks and Civil Defence leaflets were distributed by the WI who were again asked to carry out more billeting surveys.

‘I helped to carry out the billeting survey. I did the area near the High Lodge. I can’t remember who gave the instructions or how the survey was done’. Marjorie Rathbone

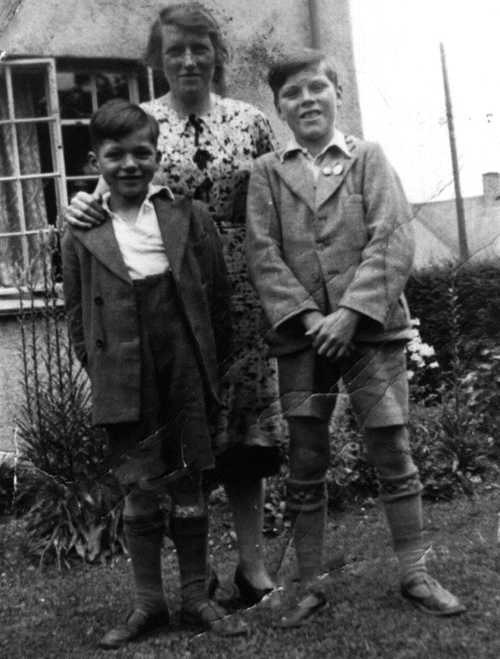

On 1st September 1939, two days before war was declared, the official evacuation of cities began. Mary Barnes aged 11 lived in London with her mother and father and two year old sister near the docks.

‘I can remember a couple of weeks before the war we used to go to school prepared to go at any time. We had to take a packed lunch and parade round the playground everyday as if we were going then we would go back to lessons and wait for the day which came on 1 September. We said ‘cheerio’ to our mums every morning not knowing if we would be going home in the afternoon.

Then, on 1st September, we were told that it was time for us to go, we were only going to be away a fortnight. We walked up the street in double file towards Upton Park station, a lot of the mums came and waved to us, some were crying. I can remember leaving school and going on a train and nobody knew where we were going and I remember we saw Windsor Castle in the distance.

Whether the teachers knew where we were going they didn’t let on, but we came to Chipping Norton [station] where there were a number of coaches waiting to meet us. We were taken to the Town Hall and given a carrier bag each, in which we had a tin of corned beef, a tin of Nestles milk, a bar of chocolate, some biscuits – I can’t remember what else, this was to help out the people who we were going to stay with. I mean we hadn’t a clue what was to happen, and there were some little tiny ones – five years old – as well.

We were taken to the Baptist schoolroom [in Milton], and I can remember looking round and seeing a number of sacks filled with straw or hay and I thought that this was where we were going to stay. But there were a lot of people there who took us off in ones and twos to meet our new families. I was first billeted with a Mrs Martin and she had a hairdressers – you know – Rawlins’ shop. Then she fell pregnant and had a baby and of course there were two of us billeted with her. So they had to find us somewhere else to live and that was when we went over to Mrs Timms in Pear Tree Close’. Mary Barnes

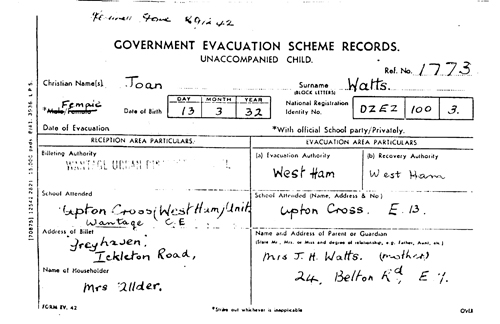

The children sent here on that first official evacuation on 1 September all came from Upton Cross School, West Ham. Ascott school received at least 32 children and two teachers, Milton at least 86 children and seven teachers and Shipton at least 63 children and five teachers all of whom had to be found accommodation. They were met by the Billeting Officers who allocated suitable billets or foster-homes with the help of the Women’s Institutes whose members were often also members of the Women’s Voluntary Services for Civil Defense (WVS).

Valerie Davis aged 6 was waiting excitedly for the evacuees’ arrival.

‘I can remember waiting for all these children and the house had all been altered upstairs and the mattresses on the floor. And we had two school teachers [Miss Watts and Miss Willis] instead of children and I cried myself to sleep. It was not long after they moved to Mrs Phillips at the shop, and then we had Mary Bond and Olive Barker. Olive didn’t stay long. I think her mother came down and took her home.

I was six years younger than Mary, six years older than my brother and I was sort of on my own in the midst of it. I remember all the evacuees about in the village – there were those at the Tibbitts. They were part of our lives then, I suppose that we just accepted them.’ Valerie Davis

Many evacuee family groups had to be split as most foster homes used were only small cottages which could only take a maximum of two. Billeting officers were anxious to avoid mixing the sexes (local and evacuated) so evacuated brothers and sisters were usually separated into different billets.

If evacuated children had problems with their billet, they could make known their complaints and grievances to their own peers, siblings and teachers, or to the local WVS, teachers and doctor. Evacuees could, and did, contact their own parents. Complaints over billets ranged from homesickness, the primitive conditions compared to their own homes, harsh discipline, and the verbal, mental, physical abuse by the foster parents.

There were also complaints from the foster parents about the habits, manners and behaviour of the evacuees and their parents. Some changes of billet were found necessary and the Billeting Officers had to make sure that the correct foster-parents were receiving the correct billeting allowance for each evacuee; 10s 6d a week for the first evacuee child and 8s 6d for every subsequent child. These rates were later changed to make allowance for age. Five shillings was paid for each teacher accommodated.

The duties of the Billeting Officer applied to those officially evacuated by the local authorities and did not apply to the military, war workers or children and families who evacuated themselves who made their own arrangements, although it was not unknown for the Billeting officer to help out. Billeting Officers did have compulsory powers to impose official evacuees on households but it is thought that hereabouts it was mostly done by persuasion. Joan Hall commented ‘Of course if you had evacuees it wasn’t your choice. If you had a spare bed you had evacuees. That was a thing that we never came to terms with‘.

Vi Smith took in the Tripps, a mother and her two children.

‘They had a committee. All places had to have them and it was according to what accommodation you’d got what you could house and who you had. I was lucky in that I had nice people, you know, who weren’t dirty or slovenly – very fortunate. But you see they had to go to school and made the schools more difficult but this one little girl was almost similar age to Barbara and you can imagine Barbara being the only little one, she treasured all her things so and Jennifer was a little bit rough. We often had words about who should have what’.

How long did she stay with you?

Well, they eventually decided they liked Milton and her husband was still in Ilford. Her husband used to come down and see them and then they decided they would try to rent a cottage in Milton to give them a bit more independence and he could come down when he was able, so they rented a cottage in Milton High Street for a time’. Vi Smith

But not every one took in evacuees.

‘I knew them all that had evacuees. I was going to have evacuees but they didn’t come to me because I had my mother in law.’ Rose Burson

‘As I was pregnant before war was declared we did not have any evacuees. Mrs Shephard, two doors away at Greenmount had two, Lily Garland and Betty Window. My mother had two, William and Grace Phillips, although later the boy was exchanged for Joyce Phillips’. Marjorie Rathbone

Although many evacuees returned to London during the period of the ‘Phoney War’, fresh official evacuations followed the beginning of the Battle of Britain and the later bombing raids. These raids also brought many who made their own way here.

Cis Miller was at home helping her mother.

‘After about four to six weeks, when we came home one day and found a big pile of suitcases on the doorstep. It turned out that many of Jim’s family had found their way down here, dumped their things on the doorstep and gone off onto the Green. There was Gran, Auntie, and an uncle and his fiancée.

It was with some difficulty that they were all fitted in. There were 14 of us and them in the house at one time. But it was so much of a problem that they had to find other accommodation on Fiddler’s Hill in Shipton. Dad stayed in London but made frequent visits. In fact, both sets of parents made visits‘. Cicely Miller

The story of Mrs Win Dolton who came to Shipton during the war, illustrates the sanctuary that the Wychwood villages offered as told before she died.

On 7 September her life changed completely. The blitz on London had began with the East End of London the main target area. When the air raid sirens sounded Mrs Dolton took shelter wherever she could, in the shelter in the garden or in a surface shelter if out shopping with her daughter, while her husband, Dave, was engaged in the gruesome task of rescue and demolition of bombed-out buildings. As the bombing intensified, and with her husband on duty, Win sought the company of others in the public shelters especially during the night raids. She often went with her daughter and a neighbour to an underground shelter at a nearby school.

That night, 7 October 1940, her neighbour came round early to say that, as they had not been unable to move on those who were already bombed out, the school shelter was already full. So they all went to shelter at St Luke’s Church. That night the school shelter received a direct hit.

Mrs Dolton decided that her luck was running out. The following morning, 8 October, Margaret’s third birthday, they left. She had heard of Shipton under Wychwood from other returned evacuees so she bought underground tickets to Paddington, but there was a daylight raid so they only got to Aldgate East.

Above ground she managed to hire a taxi to take them to Paddington with her fare paid by an unknown lady. There was another hold-up for raids on Tower Hill but she eventually reached Paddington to begin their journey to Shipton. Margaret was given a half a crown as a birthday present by a fellow passenger. Careful watch was kept on the now painted over signs until they reached Shipton under Wychwood. She stepped out onto the platform in a place she had only heard about, with her marriage lines in a tin box in one hand and Margaret on her other arm.

She carried Margaret into the village where there were given a meal by Sally and Cecil Viner in Church Street. Starting with nothing she set up home in a condemned house called Shep’s Cottage on Fiddler’s Hill and was given ‘bits and pieces’ by family, friends and neighbours. She was later joined by her sons who had been evacuated elsewhere and later by her husband, Dave, when he was released from demolition work. ‘It was a Godsend coming down here‘. She died in Shipton in 1994 and Margaret, now Mrs Hunt, is still in Shipton, living in Ballards Close.

Even when the evacuees got away from the bombing, there was no escaping the sound of the many training planes in the skies over the Wychwoods.

‘I had my cousin for a little while just to take her out of London because they were being bombed and she was getting very scared. But she wasn’t classed as an evacuee as she was a relative, but she was terrified of the planes. I always remember how frightened she was – as soon as she heard a plane coming she got under a table and put the table cloth over her, she was that frightened. She always thought they were going to drop a bomb as soon as she heard a plane’. Vi Smith

At times it was difficult to find space for the evacuees and many moved several times within the village.

‘The Hawtins next door did not take any from the first evacuation, but they took Irene Harrendence form the second evacuation. When the bombing on London began on September 1940, Betty Windows’ mother and step-father left London as they were bombed out and they came to live with us. They stayed for about two years until Mrs Windows was pregnant and they moved to two rooms with Mrs Pritchard in the laundry up the High Street. She gave birth to a 2 pound baby.

Before they moved to the laundry Mrs Woolf had put them up. She lived in the last of the three new houses in Frog Lane. Meantime, Mr Windows’ sister, Mrs Jenkins and her husband had also moved from London to Milton and they were put up by the Hawtins’ next door. Betty Windows later moved to live with Bill Hedges in The Square. Mrs Coombes, up The Square, also took in two evacuated teachers from Dagenham, Miss Clarke and Miss Willis. Geoff’s brother Harry and his wife Annie also left London during the bombing and they came to Milton to live up the High Street. They later had an evacuee, Patricia Standing, billeted on them’. Marjorie Rathbone

At the third evacuation in September 1940 when the London blitz started, there was a family of three boys whom the billeting officer had difficulty in placing. It is said they were trailed around by Miss Batt, the chairman of the local WVS, and finally ended up in Pear Tree Close. Here, Mrs Win Miles agreed to take the twins and Mrs Rose Timms the other brother – just for the night which turned out to be four years!

“That’s How It Was” Menu

These pages are reproduced from the Society’s publication “That’s How It Was”, featuring women in the Wychwoods during World War Two. The texts and images were published in the year 2000, and deserve a place in our expanding online archive. Please bear in mind as you read our texts in these pages, that we reproduce them as published in the year of publication.

Select from:

“That’s How it Was” | Introduction | Wychwood Women : The Interviewees | Declaration of War | The Arrival of Evacuees| School Time | Preparing for War at Home | Soldiers and Airmen | For the Common Cause | Dr Scott and the Canteen | Domestic Life | We Were Lucky Out Here: Food Rationing | Work for Women Outside the Home | The Effects of War