“That’s How it Was” | Introduction | Wychwood Women : The Interviewees | Declaration of War | The Arrival of Evacuees| School Time | Preparing for War at Home | Soldiers and Airmen | For the Common Cause | Dr Scott and the Canteen | Domestic Life | We Were Lucky Out Here: Food Rationing | Work for Women Outside the Home | The Effects of War

… from the Wychwoods “That’s How It Was” Publication

Preparations for war at home were being made well before 3rd September 1939. The government was particularly fearful of poison gas attack and gas masks were issued to all households, an event particularly remembered by those of our interviewees who were school age in 1939, Valerie Davis and Mary Barnes

‘Oh I remember those, they stank. And for a long time we had to carry them about and had a little rexine box, was it? And my brother, he was born in March 1939. They had a massive old coach built pram and Mother used to carry this great big gas mask about’. Valerie Davis

‘I remember having them because I remember the little babies having those ‘mickey mouse’ ones. They were horrible to wear, absolutely stifling. I can remember the first and second day and the siren went and everybody reached for their gas masks’. Mary Barnes

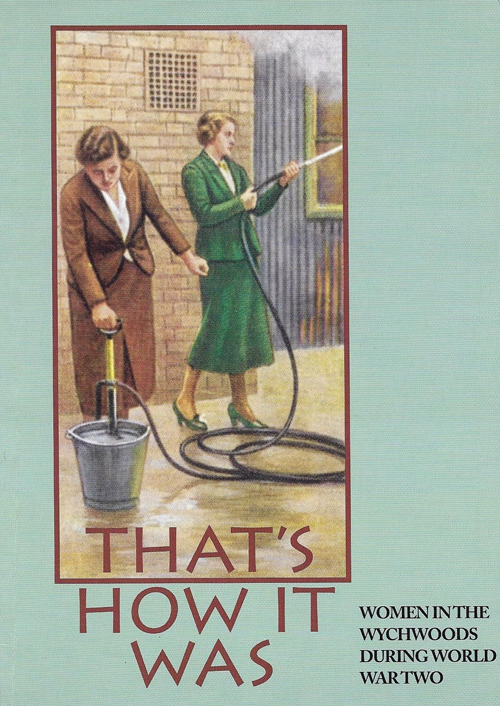

Fire fighting provision was made. Rose Burson remembered ‘We had buckets of sand, because we used to go fire fighting. And then we used to have pumps and pump water‘.

Betty Scott remembered two fires very close to her, neither caused by the enemy. At that time the doctor’s surgery was by the house in Church Path, Shipton and the school was opposite.

‘We had stirrup pumps. And of course our own surgery went up in flames during the war. They were all voluntary firemen. You know what the wooden hut of the surgery was like, you could almost reach to the roof without ladders, and they hacked at the door with their little axes. They wanted a ladder and we had to lend them our rickety ladder.

The school was going to make a canteen in a wooden hut in the playground which they used for carpentry and domestic work for girls. And they cleared out all of that and brought an army canteen there. And they’d just got it beautifully stocked up and he’d got a tortoise stove there. He made it up while he went to have his dinner at the Red Horse, and during that time the thing went up in flames and all the tins of beans and things went pop, pop, pop, and everybody kept ringing us up to say ‘Are you safe down there? Would you like to come up here?’ They thought it was guns going off’. Betty Scott

First aid lectures were held and Betty Scott was expected to use her medical training. ‘I was supposed to be in our own surgery, head of first aid workers there, then of course we all went to first aid lectures in the Red Triangle hut, I think it was’.

The whole country had to observe the blackout to avoid giving guidance to enemy bombers. One of the principal memories of our interviewers was the blackness at night with not a light allowed to show.

‘Somebody came round and jumped on you immediately for showing a light and you shouldn’t. It was very dark in the village, because there were no street lights and I always remember that it seemed as though the evenings were nothing because the people couldn’t go around so they just stayed in doors. Very restricted really’. Vi Smith

‘Mother had special frames made for all the windows covered with curtain stuff. One night I was reading in bed with a light on, and a bit of light must have been showing through and one of the Wilks came by and shouted ‘Put that light out!’ Another time we were waiting at Shipton station at night when a train stopped and a voice called out from an open window, ‘Can you please tell me where we are?’ Everything was blacked out‘. Betty Brown

Betty Scott was the Girl Guide captain. ‘I had to go over to Clanfield because the Commissioner lived there and she was giving lessons to new Guiders. You had to go after dark and in those days you had your headlights with only just a slit of light. It was very tricky going from here to Clanfield. I must have been a lot braver than I am now though only half as brave as most people’. Betty Scott

During the war Groves’ yard in Milton was the centre of the Civil Defence in the area, as it had the Wardens’ Post, mobile fire pump and rescue services. It also served as the HQ for the Milton platoon of the Home Guard and the centre for WI fruit preservation. At the beginning of the war, the air raid warning siren caused some alarm but as the warnings became more frequent they tended to be ignored.

‘My father, Ted Bolton, was responsible for the sounding of the air raid siren at Alfred Groves’ yard. He was not on the phone but Mr Walker would get in contact with him somehow, as he, Mr Walker, was chief ARP Warden who got the messages about air raids. Mr Walker said that my father was the only one who could out-talk his wife’. Marjorie Rathbone

Dorothy Harrison remembered ‘They sounded the siren for nothing. There was a siren in Ascott. It was kept at the Churchill Arms. It went on and off, and someone had to turn the handle to make it go‘.

And Brenda Bishop was delivering milk from Mr Wells’ dairy farm and recalled ‘The first air raid warning scared me stiff, and I dashed back to Poplar Farm only to be met by a very stern Mr Wells, telling me to go ahead and deliver to the customers. At the time I thought he was unfeeling but later saw that it wise as we had to learn to cope‘.

‘The day after war was declared the siren went, over in the yard. I can recall my mother running upstairs with three gas masks, one round her neck and bringing the others up, Jeff’s and mine, and the evacuees. She thought that we were going to be gassed straight away’. Cicely Miller

Betty Brown was 12 years old when war was declared.

‘We lived in The Square at the time, right in the corner, next to Lydiatt’s. They were very deaf, so whenever the siren sounded, which was on the top of Groves’ yard, I had to go round to tell them that the air raid warning had gone. The first time we heard the siren we were all in bed.

We all came downstairs and huddled under the kitchen table, except father. He stayed in bed, saying that if they wanted to kill him they could do it while he was in bed. After that we didn’t worry about any air raid warnings’. Betty Brown

Very few families had proper shelters and, most like Joan Hall, remembered ‘making a bolt for the kitchen table‘. Similarly Cis Miller said ‘we had a very big heavy table and we used to gather under the table with the evacuees and Mum. That’s where we spent our time‘.

‘We had one in the garden for the three families, Shepard, Hawtin and ourselves. It was underground, it was lit and we went down steps into it. We went down there a few times, but as Geoff said ‘ we shall catch our death of cold down there‘. Marjorie Rathbone

Although as the war progressed taking shelter was abandoned, there were at least 26 aerial attacks, mainly indiscriminate dropping of parachute mines, high explosives and incendiaries, within a ten mile radius of Shipton church in 1940, with more in 1941. They were intended for the local airfields and one probably intended for the radio station at Leafield landed on Ascott on 23 September 1940. Dorothy Harrison was working on the nearby farm.

‘It blew the side off the house of Mr Jack Young and blew away the outside toilet and a damson tree in the garden. At that time everything was rationed so very much. Hardly any sugar, and Jack Young’s wife was making jam, and when the bomb hit the side of the house and blew the stove out, she didn’t say ‘Ooh look at my kitchen’, but ‘Damn, all that sugar saved up for jam’. She had her priorities right.

They closed the High Street and when [my] Dad came home from work he was unable to get home. They told him that the house was damaged but nothing more. ‘Bugger the house, how’s my family’ was his response. They were okay. Dorothy Harrison

Janet Wallace left home for boarding school in Yorkshire at the beginning of January 1943 and recalled vividly what happened there when there was an air raid.

‘Warnings usually came at night which meant we had to get up quickly, put on dressing gown and slippers, take an eiderdown or rug and assemble in the front hall, given a small green cushion and told to settle down in the floor and try to sleep. One night we had three alerts. Although we were not bombed, there were plenty of places around that were badly hit. We had daily prayers and we used to assemble once or twice a week to take part in a Litany during which we prayed for named family members who were in the armed forces.

We had a large map of Europe on the wall indicating how the war was going. We had to wear school uniform but we were always cold in the winter. When travelling to and from school we had to take our gas masks, identity cards and ration books with us always. Trains were always very full with civilians and troops, all train windows had some sort of lattice glued onto them. When peace was declared I was returning to school, but stayed overnight in London and enjoyed their bonfire and fireworks celebrations’. Janet Wallace

“That’s How It Was” Menu

These pages are reproduced from the Society’s publication “That’s How It Was”, featuring women in the Wychwoods during World War Two. The texts and images were published in the year 2000, and deserve a place in our expanding online archive. Please bear in mind as you read our texts in these pages, that we reproduce them as published in the year of publication.

Select from:

“That’s How it Was” | Introduction | Wychwood Women : The Interviewees | Declaration of War | The Arrival of Evacuees| School Time | Preparing for War at Home | Soldiers and Airmen | For the Common Cause | Dr Scott and the Canteen | Domestic Life | We Were Lucky Out Here: Food Rationing | Work for Women Outside the Home | The Effects of War